How Poverty and Depression Impact a Child’s Social and Emotional Competence

By Abby C. Winer and Ross A. Thompson, UC Davis

To grow up in poverty can have a lasting impact on a child. What is less understood is how it affects the early relationships that shape a child’s social and emotional growth.

In ongoing research, Center for Poverty Research Affiliate Ross A. Thompson and Graduate Student Researcher Abby C. Winer have found that a mother’s level of education, household income, and symptoms of depression have lasting effects on her child’s social competence in early childhood.

Key Findings

- Education level, household income, and symptoms of depression have short-term effects on preschoolers’ understanding of emotions, and lasting effects on children’s social competence in early childhood.

- Rather than household income, a mother’s educational attainment was the strongest, most direct predictor of a child’s understanding of emotions at age 4.

- A model of the pathways from demographic and emotional risks to children’s social and emotional competence explained 59% of the variance in children’s social and emotional competence over time.

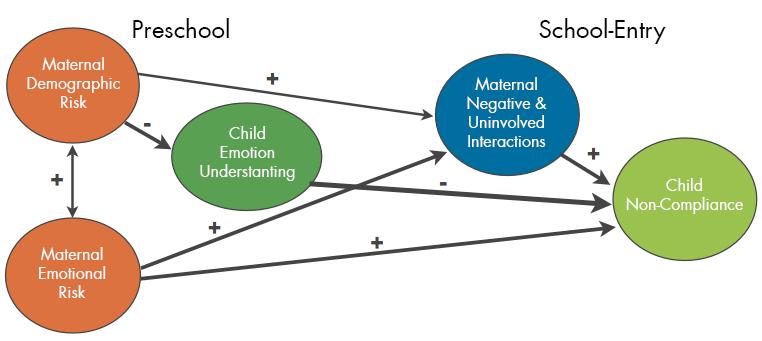

How can we explain the relationship between the risk factors associated with poverty and a child’s developing social and emotional competence? A complete model of this relationship shows that a mother’s level of education, income, and emotional risk (such as depression) all have short-term impacts on her child’s understanding of emotions, but also have long-term impacts on the quality of the time they spend together.

Children’s early emotion understanding predicts their later non-compliance. Children who better understand emotions are less likely to show non-compliant behaviors as they grow older. While demographic risk does not directly predict non-compliant behavior when a child enters school, it does predict a mother’s interaction with her child, which in turn leads to differences her child’s compliance. Mothers with lower household income and lower levels of education were more likely to be more negative in their play interactions with their children.

This ongoing study has so far found that a mother’s level of education, household income, and depressive symptoms have direct, lasting effects on her child’s social competence in early childhood. Children in families with greater demographic and emotional risks are less able to understand emotions in others and themselves. This leads to more difficulty following rules, which puts them at a disadvantage compared to their peers as they enter formal schooling.

Measuring Risks and Effects

This study analyzes data from a recent short-term longitudinal

study that involved observing how a sample of multi-lingual,

economically diverse mothers interacted with their children

during free play and clean-up sessions. The study also involved

measuring the children’s social-emotional competence. The

observations took place when the children were four years old and

then again 18 months later.

Researchers Thompson and Winer used this data to index demographic risk as a mother’s level of education and household income, and assessed emotional risk by measuring a mother’s feelings of depression and distress. The researchers then coded mother-child interactions for the frequency of negative feelings expressed by mothers during the sessions, and for the mother’s overall level of involvement with their children.

The researchers also indexed the children’s social-emotional competence based on their responses in a puppet-based emotion-understanding task at four years old, and then 18 months later in an age-appropriate task to assess their ability to comply with rules and standards of conduct.

Demographics and Depression

This study finds that a mother’s educational attainment, rather

than household income, was the strongest, most direct predictor

of children’s emotional understanding at age four. Mothers who

completed higher levels of education had preschoolers who were

better able to identify emotions, even in situations where the

other person felt differently than they would.

Demographic risk factors were not found to directly predict children’s social competence at school entry. Instead, household income and educational attainment were associated with the quality of mother-child interactions at 5 ½ years of age. Lower household income and educational attainment were associated with greater amounts of negativity in mothers’ interactions with their children.

Emotional risk factors predicted differences above and beyond what could be explained by a mother’s income and education. Emotional risk in preschool was a direct, strong predictor of children’s social competence at school entry. Indirectly, emotional risk was associated with mothers’ interactions with their children, which in turn, predicted deficits in children’s social competence. Mothers with greater depressive symptoms when children were four years old were more negative and less involved in their interactions with their children at 5 ½ years of age.

A model of the pathways from demographic and emotional risk over time on children’s compliance explained 59 percent of the variance in children’s social and emotional competence at 5 ½ years of age. The model revealed that these risk factors were associated with children’s social and emotional competence through their short-term effects on children’s emotion understanding and their long-term effects on the quality of mothers’ interactions with their children.

This study finds that over time, a mother’s depressive symptoms are a better predictor of social competence than both income and education. Children whose mothers showed more symptoms of depression when they were four years old were more likely to show overt non-compliance 18 months later at 5 ½ years of age.

Pathways out of Risk

This study contributes to our understanding of how poverty is

transmitted across generations. The findings illustrate that both

demographic and emotional risk factors associated with poverty

affect children’s social and emotional competence over time. The

pathways out of demographic and emotional risk are multiple and

complex, but may be reversible by disrupting the compounding

effects of familial risk on a child’s development.

To do so, efforts should target both parents and children. These efforts might include family income support and other forms of economic assistance, as well as mental health services to address the emotional consequences of poverty for family members. According to this study’s findings, helping mothers reach higher levels of emotional well-being over the course of the 18 months, and coaching children to identify and understand emotions in themselves and others could both help to diminish the long-term effects of early demographic and emotional risk.

Meet the Researchers

Abby C. Winer is a Ph.D. candidate in Human Development

at UC Davis. Her research interests include relational and social

cognitive processes in children’s social and emotional

development, early prosocial, conscience and moral development

and research with at-risk and diverse populations.

Ross A. Thompson is Distinguished Professor of Psychology at UC Davis. His research focuses on the applications of developmental research to public policy concerns, including school readiness and its development, early childhood investments, and early mental health.