State Public Insurance Reduced the Incentive to Work among Childless Adults

by Laura Dague, Texas A&M University; Thomas DeLeire, Georgetown University and Lindsey Leininger, University of Illinois at Chicago

Public insurance can provide needed medical coverage for those who cannot afford it. Considering that private insurance is often bound to employment, a public option could have an impact on the labor market if it reduces incentives to work.

This new study, supported in part by a 2012 Center for Poverty Research Small Grant, finds that public health insurance may lead to lower rates of employment and earnings among low-income childless adults. These findings may have implications for the Affordable Care Act.

Key Findings

- The receipt of public insurance in Wisconsin led to a 2.4 to 10.5 percentage point decline in quarterly employment rates among low-income childless adults for up to 9 quarters following enrollment.

- The net effect of insurance enrollment on earnings, including those who lost or changed jobs, was a reduction of approximately $125 to $445 of income per quarter.

- Early results show that childless adults not enrolled in public health insurance are more likely to change jobs than those enrolled, suggesting that public health insurance did not reduce job lock in this case.

Medicaid is currently the third largest federal domestic spending item after Medicare and Social Security. Among states it is the second largest spending item after education. Nearly 60 million low-income adults and children benefit from the program. Up to 21.3 million additional low-income adults could ultimately gain coverage with the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Initial Congressional Budget Office projections suggested that the law would increase insurance coverage by 33 million people by 2019, with low-income childless adults composing the majority of those covered under the Medicaid expansion. Under the subsequent Supreme Court decision, which made Medicaid expansion optional for states, childless adults are still projected to gain large-scale eligibility for Medicaid as of 2014.

While extensive research shows that such cash and in-kind transfer programs reduce labor supply, findings on Medicaid’s impact on labor is mixed. In this study, researchers examined a recent policy reversal in Wisconsin, which occurred when a major public insurance expansion for childless adults was abruptly frozen.

BadgerCare Plus

Launched in January 2009, Wisconsin’s BadgerCare Plus Core Plan

provided health insurance to adults without dependent children

who earn below 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). In

2009 that figure was $21,660 for an individual. Enrollees

received managed-care benefits at little cost. With few

exceptions, eligibility excluded those with any private coverage,

and those who quit their jobs or voluntarily dropped any health

coverage the prior 12 months.

Enrollment reached a high of 65,057 and quickly exhausted the program’s budget. After suspending enrollment that October, the waitlist reached 89,412 by December 2010. The Core Plan ended on December 31, 2013.

Those below 100 percent FPL are now eligible for coverage under Wisconsin’s standard Medicaid package. Those above FPL are expected to participate in the health insurance marketplace created by the ACA, though Wisconsin has so far opted out of its federally incentivized Medicaid expansion.

Measuring Labor Outcomes

This study compares employment among able-bodied, childless

adults who enrolled in the BadgerCare Plus Core Plan to those on

the waitlist after enrollment was frozen. Researchers matched

state administrative records on Core Plan applicants to earnings

records from Wisconsin’s unemployment insurance (UI) system from

Q1 2005 through Q4 2011 using Social Security numbers.

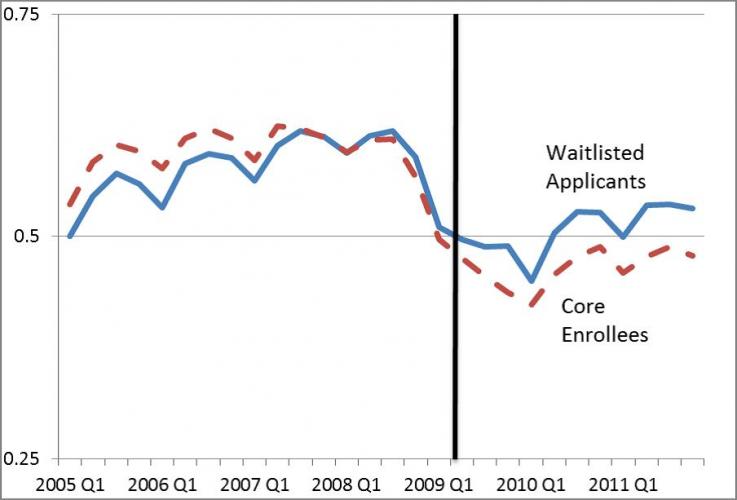

To measure Core Plan enrollment’s impact on employment, earnings, job transitions and self-employment, the researchers considered average quarterly employment over the Q2 2009 to Q4 2011 period. In this study, an individual is defined as employed if he or she had any earnings in a quarter, regardless of hours worked.

Employment and Earnings

Findings suggest that public insurance was a substantial work

disincentive among low-income childless adults. Waitlisted

applicants had higher employment rates than enrollees in quarters

following the cut-off date. The estimated effects range from 2.4

to 10.5 percentage points depending on the analytical models, and

controlling for sex, age, and county of residence. The net effect

of enrollment on earnings was a reduction of approximately $125

to $445 of earnings per quarter, including those who lost or

changed jobs.

That the vast majority of those with private health plans have them through their employers suggests that accessible public insurance would lead to more job transitions. Early results in this study suggest the opposite: waitlisted applicants were between three and seven percentage points more likely than enrollees to change jobs.

These results took place in the context of a state economy with relatively high unemployment (8.5% in 2010 and 7.5% in 2011, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). One might expect larger effects on employment and job-transitions in a more robust economic environment. For example, the estimated effects were large in counties with unemployment rates less than or equal to ten percent, but nonexistent in counties with unemployment rates above ten percent.

Policy Implications

Policymakers should be aware of possible reductions in work among

childless adults with the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. However,

extrapolating from the Wisconsin Core Plan experience may not be

straightforward. Unlike the Core Plan, Medicaid is an entitlement

program, which would exacerbate any employment disincentive

relative to Medicaid. After Core Plan enrollment ended in October

2009, any member who left (perhaps as a result of gaining

insurance through a new employer) could not re-enroll.

Individuals would be free to exit and reenter Medicaid as their

eligibility changes.

Other differences have less certain implications. For example, the Wisconsin program featured eligibility all the way up to 200 percent of FPL, while Medicaid expansions will serve only those up to 138 percent of FPL. Differences in requirements for coverage under the Core plan versus Medicaid may also be important.

Meet the Researchers

Laura Dague is an Assistant Professor at the Bush School

of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University.

Thomas DeLeire is a Professor of Public Policy at Georgetown University.

Lindsey Leininger is an Assistant Professor of Health Policy & Administration at the University of Illinois at Chicago.