Penalties for Poverty Risks Drive High Poverty in the United States

By Ryan Finnigan, UC Davis

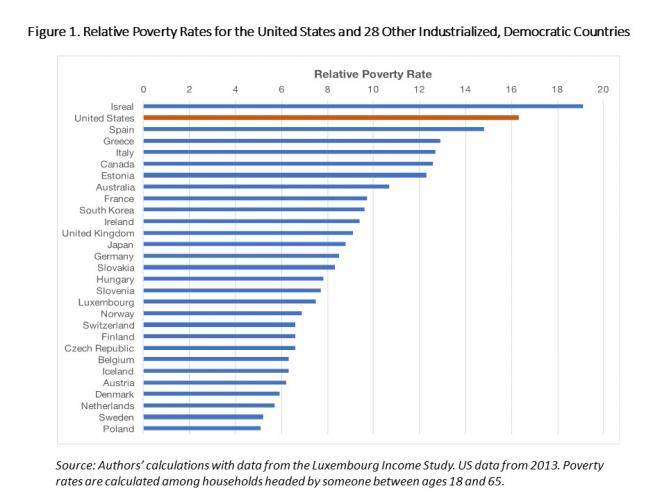

When measured relative to median income, poverty in the United States, at 16.3 percent, is much higher than in many industrialized, democratic countries. To explain this, scholars, politicians, and the public often focus on the risks of poverty. Risks are characteristics more common among the poor than the non-poor, like low education, unemployment, single motherhood, or young age of the head of household. In a study I conducted with David Brady and Sabine Huebgen, we found that the cause of relatively high poverty in the U.S. is not that these factors are more common, but that the penalties applied to them are high.[1] We also found that poverty is lower in countries with more generous welfare states, and that the risk of poverty due to unemployment or low education is also lower in those countries.

Key Facts

- At 16.3%, relative poverty is much higher in the U.S. than in other industrialized, democratic countries.

- Low education, unemployment, single motherhood and early household formation put households at greater risk for poverty, but these factors are not substantially more common in the U.S. and do not explain the high poverty rate.

- Greater penalties associated with these risk factors help explain high U.S. poverty.

Poverty in the United States, at 16.3 percent, is much higher than in many industrialized, democratic countries. To explain this, scholars, politicians, and the public often focus on the risks of poverty. Risks are characteristics more common among the poor than the non-poor, like low education, unemployment, single motherhood, or young age of the head of household. In a study I conducted with David Brady and Sabine Huebgen, we found that the cause of relatively high poverty in the U.S. is not that these factors are more common, but that the penalties applied to them are high.[1] We also found that poverty is lower in countries with more generous welfare states, and that the risk of poverty due to unemployment or low education is also lower in those countries.

Social science research often compares contemporary U.S. poverty rates to those from earlier years to determine whether changes in individual or family characteristics explain changes in poverty trends. Many politicians and scholars express concern that growth in single motherhood contributes to relatively high poverty rates.[2] Our research asks whether these characteristics explain the differences in poverty rates between the U.S. and other countries.

We compared countries using relative poverty rates, defined as income below half of a country’s median income when adjusted for household size, taxes, and transfers.[3] The data we used for the study came from the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS), an archive of nationally representative surveys on income and other characteristics covering dozens of countries.[4]

Figure 1 shows the poverty rates for the 29 countries studied. Poverty is more than twice as high in the U.S. as many Northern and Western European countries, including Norway and Switzerland. Accounting for different standards of living, Central and Eastern European countries have substantially lower poverty rates than the United States.

Risk Factors, Prevalences and Penalties

Our study examined four major risk factors for poverty: single motherhood, low education, unemployment, and young age of head of household. Existing research on poverty in the U.S. suggests that these factors are the most important predictors of poverty.* Thus, anti-poverty policy in the U.S. aims to reduce the percentage of the population (i.e. prevalence) with a given risk factor.

We found that high prevalence rates of these four risk factors do not explain the higher poverty in the U.S. Of the 29 countries, the U.S. has the second highest poverty rate, but ranks 20th in the prevalence of at least one of these four risk factors. The U.S. ranks third in the prevalence of single motherhood, but has a relatively low prevalence of low education and unemployment. Thus, prevalence of risk factors is not necessarily the reason behind higher poverty rates.

Penalties Help Explain Higher Poverty Rates in the U.S.

The connection between risk factors and poverty depends on how strongly the factors are associated with poverty, known as the penalty of a risk. Though prevalences of the risks are below average compared to other countries, the penalties for all four risks are greater. The penalty for low education is the highest of all the countries. The penalty for single motherhood is the third highest, for unemployment the fifth highest, and for young household headship the ninth highest. Thus, prevalence of risk factors is not the reason for high poverty in the U.S.; relatively large penalties associated with these risks are.

Welfare Generosity and Differences in Poverty Between Countries

A natural question relates to the role of countries’ political systems and welfare systems.[5] We found that poverty is significantly lower in countries with more generous public welfare programs. The U.S. has one of the lowest levels of generosity. Welfare generosity was also more strongly associated with poverty than were cross-national differences in the prevalences of the four risks in our study.

Despite the prominent focus on the prevalence of risks for poverty in the U.S., our results show that prevalence does not explain high poverty rates. Rather, the four risk factors carry unusually strong penalties in the U.S. compared to other countries. A more generous safety net could reduce the penalties associated with the major risk factors. In this sense, the U.S. is an atypical context to study for developing general explanations of poverty, in either developed or developing countries.

Ryan Finnigan is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at UC Davis. (rfinnigan@ucdavis.edu)

* A recent example is the American Enterprise Institute and Brookings Institute’s “Consensus Plan for Reducing Poverty and Restoring the American Dream,” a bipartisan plan that encourages marriage and delayed parenthood, increasing employment especially among the less-educated, and increasing education.

References

[1] Brady, David et al. 2017. “Rethinking the Risks of Poverty: A Framework for Analyzing Prevalences and Penalties.” American Journal of Sociology.

[2] Haskins, Ron and Sawhill, Isabel. 2016. “The Decline of the American Family: Can Anything be Done to Stop the Damage?” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

[3] Rainwater, Lee and Smeeding, Timothy. 2004. “Poor Kids in a Rich Country: America’s Children in Comparative Perspective.” New: York: Russel Sage Foundation.

[4] Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database. 2014. http://lisdatacenter.org.

[5] Brady, Davis. 2009. “Rich Democracies, Poor People”. New York: Oxford University Press.