Welfare-Involved Children in Special Education Most Likely to Suffer Supervisory Neglect

By Kevin A. Gee, University of California, Davis

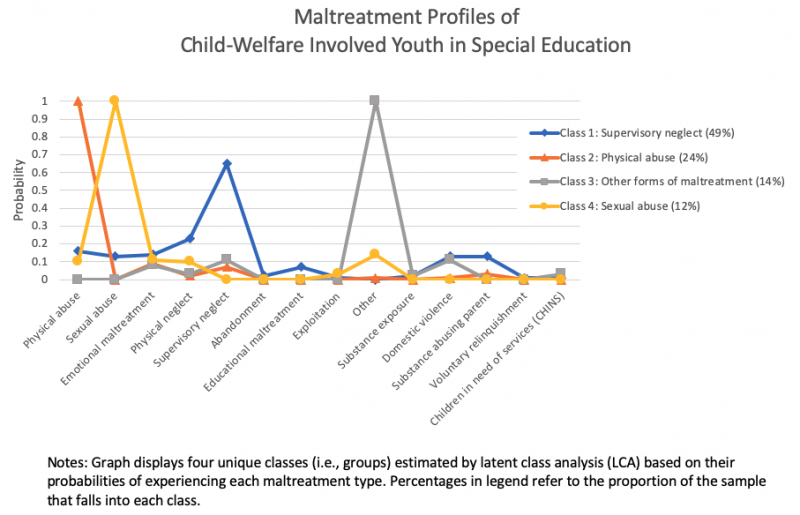

I investigated the maltreatment profiles of child welfare–involved children in special education, examining how those profiles influenced their internalizing and externalizing behaviors. I analyzed data on a sample of 290 children representing approximately 233,000 children involved in the child welfare system and in special education. In doing so, I applied a range of measures, including the poverty level, mental health and marital status of caregivers. My analyses revealed four maltreatment classes, listed by predominance: supervisory neglect, physical abuse, other forms of maltreatment, and sexual abuse. Relative to children in the sexual abuse class, children had higher teacher-reported internalizing problem behaviors if their predominate maltreatment class was either supervisory neglect or physical abuse. Understanding the circumstances and consequences of maltreatment for child welfare–involved children in special education can help better inform ways to promote their educational success.

Key Facts

- The most common form of maltreatment suffered by child welfare-involved children in special education is supervisory neglect, followed by physical abuse.

- Children who experienced supervisory neglect and physical abuse had higher internalizing behaviors relative to those sexually abused.

- Understanding the socioecological determinants of different maltreatment profiles may help teachers and agencies to provide more appropriate and effective supports.

Among the four recognized categories of maltreatment (neglect, physical abuse, psychological maltreatment, and sexual abuse,[1] neglect and physical abuse are the most prevalent among children with disabilities. Knowledge of the relationship between maltreatment profiles and disability introduces complexities into how special education and related services might need to be delivered. Although maltreatment and disability often co-occur and can have a bidirectional relationship,[2] there is a lack of consistent and reliable information about the maltreatment experiences of child welfare system (CWS)–involved children eligible to receive special education services.[3]

Early models explaining the maltreatment of children with disabilities attributed the risk of abuse to children’s own behaviors and attributes, such as their disability type, gender, and age.[4] Later, caregiver stress or frustration models were developed, which suggested that the nature of a child’s disability can place increased emotional, economic, and physical demands on caregivers.[5] More recent ecological models depict a nested series of influences, extending beyond children and their interactions with their caregivers, to their family environments, familial social networks, and communities.Influential risk factors for maltreatment include parental history of abuse, neighborhood poverty, and parental social networks.[6]

My research questions were twofold.[7] Firstly, what are the maltreatment profiles of CWS-involved children who were eligible to receive special education services? Secondly, among such children, do those with different maltreatment profiles have different internalizing and externalizing behaviors?

Exploring Classes, Circumstances and Effects of Maltreatment

I used latent class analysis and hierarchical linear modeling to analyze data on a sample of 290 children (63 percent male, 37 percent female, average age 11 years) from the National Survey on Child and Adolescent Well-Being II. When weighted, this sample represented approximately 233,000 children involved in the child welfare system and in special education. This longitudinal data set includes three waves of data collected between 2008 and 2012. It captures children’s well-being, including their performance on a battery of standardized cognitive and behavioral assessments, as well as information reported by children’s caregivers, welfare caseworkers, and teachers.

The most prevalent form was physical maltreatment, followed by supervisory neglect and then sexual maltreatment. The most common disability (35 percent) was a specific learning disability. Roughly 15 percent of the children had an emotional disturbance. Equal proportions had either an intellectual disability or a speech or language impairment. In terms of demographics, the sample contained a higher proportion of boys than girls. Over half the sample was White, and about a quarter of children were Hispanic. A majority were cared for by a biological or adoptive parent, and lived with caregivers who had incomes ≤200% of the federal poverty level.

Supervisory Neglect Most Common, Most Predictive of Internalizing Behaviors

I detected four maltreatment classes in the data: supervisory neglect, physical abuse, other maltreatment, and sexual abuse. Of these, supervisory neglect was the most common (49 percent), followed by physical abuse (24 percent). These children also had probabilities of being physically neglected, physically abused, or sexually abused (approximately 10 percent). Children in the third-most common class (14 percent) mostly experienced other forms of maltreatment—educational maltreatment, for example. Finally, 12 percent were classified as predominately experiencing sexual abuse.

These maltreatment classes, as a whole, did not significantly relate to children’s externalizing behavior. However, specific maltreatment classes significantly predicted their internalizing behavior scores. Children who were in the physically abused class had higher internalizing behaviors versus those in the sexually abused class. Similarly, children who were in the supervisory neglect class had higher internalizing behaviors versus those in the sexually abused class.

Understanding the Socioecological Determinants of Maltreatment Profiles

Why did supervisory neglect emerge as the most prominent maltreatment profile? Perhaps due to the challenges that caregivers may face in supporting children with disabilities. Given the specialized needs and responsibilities associated with their care, children with disabilities can face a heightened risk for neglect. Consequently, there may be more opportunities for parents and caregivers to overlook those needs—especially if parents have limited resources to care for their children. Not only can supervisory neglect lead to physical neglect; it is also more salient in mediating a family’s social disadvantage on older rather than younger children’s antisocial behaviors.

Caseworkers and teachers may both need to augment behavioral supports and interventions for children whose maltreatment profiles show predominate patterns of either physical abuse or supervisory neglect. Furthermore, though it is always difficult to disentangle whether abuse precedes disability, information about maltreatment profiles and their distinct behavioral effects can help guide decision making about the personalized supports that can be integrated into support plans. For special education teachers and team members, including school psychologists, understanding maltreatment and its consequences can better inform the types of supports that children need in order to learn, and can further contextualize challenges that may hinder progress in response to interventions. Knowledge of children’s maltreatment profiles can also be instrumental in formulating broader safety objectives within their IEPs.

Children with disabilities develop within a nested system of influences. Researchers and policymakers alike should work to illuminate and understand the socioecological determinants—poverty, for example—of different maltreatment profiles, and to highlight key mechanisms that underlie the reciprocal relationship between these profiles and disabilities.

Kevin A. Gee is an Associate Professor of Education at UC Davis.

References

[1] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Child maltreatment 2014. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2014.pdf

[2] Crosse, S. B., Kay, E., & Ratnofsky, A. C. (1992). A report on the maltreatment of children with disabilities. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED365089.pdf

[3] Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2018). The risk and prevention of maltreatment of children with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/focus.pdf

[4] Leeb, R. T., Bitsko, R. H., Merrick, M. T., & Armour, B. S. (2012). Does childhood disability increase risk for child abuse and neglect? Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 5, 4–31. doi:10.1080/19315864.2011.608154

[5] Ammerman, R. T., Van Hasselt, V. B., & Hersen, M. (1988). Maltreatment of handicapped children: A critical review. Journal of Family Violence, 3, 53–72. doi:10.1007/BF00994666

[6] Algood, C. L., Hong, J. S., Gourdine, R. M., & Williams, A. B. (2011). Maltreatment of children with developmental disabilities: An ecological systems analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 1142–1148. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.02.003

[7] Gee, K.A. (2020). Maltreatment Profiles of Child Welfare–Involved Children in Special Education: Classification and Behavioral Consequences. Exceptional Children. 86 (3) 237–254. doi:10.1177/0014402919870830