Support for the ACA Among its Beneficiaries May Secure its Future

By Adrienne Hosek, UC Davis

A decade after it passed into law, a majority of Americans now support the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In a recent study, I investigated whether the policy itself, through its beneficiaries, changed public opinion and sowed the seeds of its own defense against efforts to repeal it. I found that individuals who enrolled in plans on the health insurance marketplaces had significantly more positive opinions of the ACA after implementation. Previously uninsured Medicaid enrollees also reported improved opinions, though results were not statistically significant. In contrast, uninsured individuals residing in states that did not expand Medicaid became significantly less supportive of the law. Changes in opinion persisted up to the 2014 midterm elections. I concluded that public support for the ACA was enhanced when its beneficiaries became more positive toward it during implementation. Like Medicaid before it, the ACA—or some other, similar form of government-organized and subsidized health insurance market—may be on its way to becoming an “untouchable” policy.

Key Facts

- Efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act outright have failed, and a majority of Americans now support it.

- Individuals who enrolled in plans on the health insurance marketplaces had significantly more positive opinions of the ACA after implementation.

- Individuals whose income would have qualified them for Medicaid, but who remained uninsured as a result of their state’s decision not to accept federal funds to expand Medicaid, became significantly less favorable of the law.

- As more individuals come to rely on it for their health care, the ACA may, like Medicaid before it, soon become an “untouchable” policy.

With the creation of the ACA marketplaces (also called exchanges), the ACA provided a new source of health insurance. It also reformed and extended other elements of the existing health insurance system. Until recently, however, a bare majority of Americans consistently opposed the law with only a fraction of Americans expecting to benefit from it.[1,2]

During the first period of open enrollment, in winter 2013–14, the government implemented several policies, most significantly the roll-out of the marketplaces and Medicaid expansion. Some states opened online health insurance marketplaces, and the federal government opened a marketplace on behalf of the remaining states. These marketplaces guaranteed individuals without employer-provided health insurance access to individual insurance policies with comprehensive coverage at group rates, often with the help of federal subsidies.

These ACA policies benefited the insured as well as the previously uninsured. An estimated 8.4 million nonelderly adults gained insurance in 2014, almost always through Medicaid expansion or plans individually purchased on the marketplaces.[3] For the previously insured, the marketplaces provided individuals at risk of losing their coverage a guaranteed replacement. In the first period of open enrollment, Medicare enrollees experienced a modest benefit. Other insurance types did not receive new benefits or pay significant costs during the first enrollment year, nor did most perceive any benefits or costs aside from a fear that they might face higher health costs in the future.

In my study, I observed whether individuals enrolled in health insurance and the type of insurance they obtained.[4] I then examined how this experience affected their opinion of the ACA. This rich panel data allowed me to estimate the effect of policy implementation on policy preferences, while controlling for previous ACA opinion.

Observing Opinion of the ACA, Before and After Implementation

The data came from the American Life Panel (ALP), an ongoing panel that started in January 2006 and is representative of the US adult population. The ALP features 4,200 respondents recruited from several sources between 2002 and 2012 and includes several series of themed surveys. I drew primarily on the ACA series, which began in August 2013. I constructed a panel through which I could observe respondents’ insurance status prior to the ACA; opinions of the ACA in the month before the start of the open enrollment period, the type of insurance they enrolled in during open enrollment, and their opinion of the ACA after enrolling or after open enrollment ended. The ACA series of the ALP also included questions about respondents’ expectations of the law’s impact on health care access and cost and the likelihood of having to pay a tax penalty. I drew postenrollment political variables from the midterm-election series conducted between October 10 and November 13, 2014.

I used an individual-level panel design to control for other factors, such as political variables, that affect ACA opinion and are correlated with insurance status and type. I compared individuals who dropped out of the panel to those who remained in the panel on preenrollment ACA opinion, 2013 insurance type, and socioeconomic and political characteristics for the three periods investigated in the analysis: to the end of open enrollment period, through August, and up to the 2014 midterm elections. I considered whether the attitudes of those who obtained insurance through the marketplaces or Medicaid depended on previous insurance status and state of residence. I considered whether residence in a state that chose not to accept federal funds to expand Medicaid mediated the effects of being uninsured or obtaining insurance through the marketplaces, Medicaid, or Medicare.

ACA Support Increased Among the Newly Insured, and Others

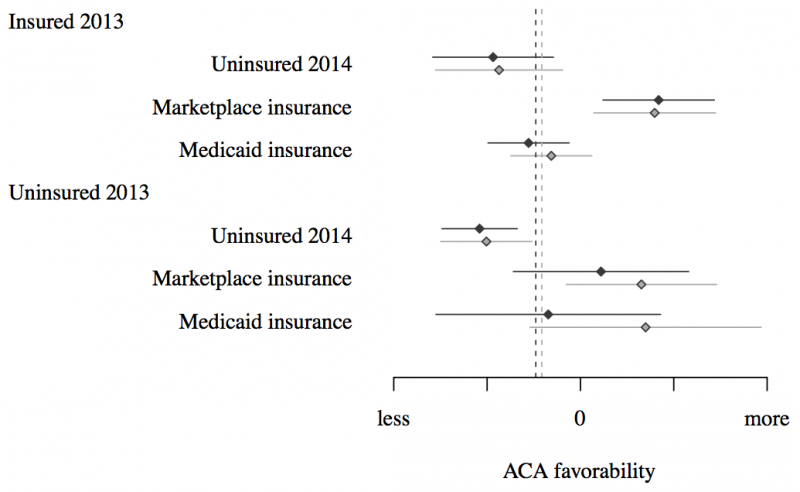

I found that individuals with marketplace insurance, Medicare enrollees, and individuals who selected “other” insurance all had more favorable opinions of the law after enrollment (Figure 1). The change in attitudes for the marketplace and Medicare groups persisted to August 2014, indicating that ACA implementation had a lasting impact on ACA opinion for these groups. Individuals enrolled in Medicare also became significantly more favorable toward the law and optimistic about its effect on the country postenrollment. Individuals who selected “other” as their insurance type were the only other group to have significantly more positive opinions of the law after enrollment. However, the change in opinion, while still more favorable, was no longer significant in August.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Two groups had significantly less favorable opinions of the ACA after enrollment: individuals with military or veteran coverage and those unable obtain insurance for 2014 in states that chose not to expand Medicaid. The effect for military/veteran coverage was substantively small and disappeared by August. In comparison, the uninsured experienced a large drop in favorability of the law, which persisted until August. Possible explanations include an unrealized promise of coverage or the fear of having to pay a tax penalty in the next tax period. Twenty states refused federal funds to expand Medicaid coverage in the first year of implementation, leaving many individuals without insurance. Individuals in these states whose incomes would have made them eligible for Medicaid but were left uninsured were significantly less favorable of the law. They may have lost faith in the ACA’s promise of insurance for all after they did not gain access to affordable insurance during the first enrollment period. Those who lost their insurance coverage in 2014 also were less favorable toward the law, but the effect was not significant.

Policy Preferences Can Transcend Partisan Views

In the few months between the start and close of open enrollment, opinions of the ACA among individuals who enrolled in insurance plans on the health insurance marketplaces improved. To a lesser extent, individuals on Medicare also reported improved attitudes of the ACA. My study therefore provides rare evidence that, under certain circumstances, policies can affect the policy preferences of impacted groups, moving them away from their partisan views. Still, and despite the fact that improvements in ACA favorability persisted, I found no evidence that changes in opinions of the law resulting from implementation impacted the likelihood of voting for a Democrat candidate in the 2014 House midterm elections. However, voters do not have to vote for a different party in order for a policy to affect politics. The candidates they elect may become more reluctant to vote to repeal the ACA as public opinion in their district shifts in support of the law.

Since the first year of ACA implementation, the trend has been for states to reverse their initial decision not to accept Medicaid expansion funds. As more and more individuals rely on the ACA (or a largely similar program) for their health care, it is possible that the ACA will become another “untouchable” policy, joining Medicare on the third rail of politics. While aspects of the ACA may well change in the future, it seems quite possible that some form of government-organized and subsidized health insurance market will become a widely accepted method for filling the gaps in the US employer-based insurance system.

Adrienne Hosek is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Davis.

References

[1] Fingerhut, H. 2017. “Support for 2010 Health Care Law Reaches New High.” February 23. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

[2] Chattopadhyay, J. 2017. “Is the Affordable Care Act Cultivating a Cross-Class Constituency? Income, Partisanship, and a Proposal for Tracing the Contingent Nature of Positive Policy Feedback.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 43(1): 19–67.

[3] Skopec, L., Holahan, J., and Solleveld, P. 2016. “Health Insurance Coverage in 2014: Significant Progress, but Gaps Remain.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

[4] Hosek, A. 2019. Ensuring the Future of the Affordable Care Act on the Health Insurance Marketplaces. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 44(4):589-630. DOI: 10.1215/03616878-7530813.