School Closures Disproportionately Affect Disadvantaged Communities

By Noli Brazil, University of California, Davis

As public-school closures have increased in number across U.S. cities, opponents have argued that the closures bring many negative consequences, such as greater local crime rates. In a recent study of the 2013 Chicago mass school closure, during which 49 elementary schools were shut, I tested this claim. Looking at each school’s status after closure (vacant, repurposed, or merged with an existing school), I found that vacancy and repurposing into a non-school were associated with decreased crime. In contrast, merging a closed school with an existing school was associated with increased crime. The vacancy and repurposing effects were concentrated in the 75-meter area surrounding the school, and disappeared after a year. The student-merger effect persisted over time, however, and across larger spatial scales. My results suggest that the relationship between closure and neighborhood crime is not straightforward. Given that closed schools are often located in poor, minority neighborhoods, policy makers should prioritize proper planning and cost-benefit analysis to ensure that disadvantaged communities do not experience unnecessary increases in hardship.

Key Facts

- In 2013, Chicago experienced the largest mass school closure in U.S. history when it closed 49 of its elementary schools—most of which were located in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

- The effects of these closures on local crime rates were much wider than previously thought, particularly when a closed school was merged with a non-closed one.

- Adequate community engagement, cost-benefit analysis and long-term planning are all crucial to mitigating the negative consequences of public-school closures.

Between 2002 to 2011, closures per 1,000 schools in the 100 largest metropolitan areas of the U.S. increased from 5.5 to 10.6.[1] Compared to all non-closed schools, closed schools are located in significantly poorer neighborhoods with a greater presence of non-white residents. Opponents of school closures cite increased crime as one of the most prominent negative consequences for such neighborhoods. According to broken windows theory, the disorder attached to school building vacancy after closure will attract crime to the area.[2] Furthermore, displaced students are forced to cross rival gang territories to attend other schools, thus elevating community conflict and violence.[3]

In 2013, Chicago experienced the largest mass school closure in U.S. history when it closed 49 of its elementary schools. These schools were concentrated in disadvantaged neighborhoods in the south and west sides, in historically disinvested and primarily black communities. In order to accommodate the nearly 12,000 displaced students affected by the mass closure, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) designated specific welcoming schools for each of the closed schools. The welcoming schools each received, on average, approximately 150 displaced students, accounting for about 32 percent of their student population in fall 2013.[4] Enrollments at some of the welcoming schools almost doubled. Students merged together typically came from neighborhoods with rival youth gangs; the district’s Office of Safety and Security either made moderate efforts to help mitigate potential conflict or was unaware of these boundaries.

Measuring the Impact of School Closures on Crime

In my study, I estimated the effects of school closures on crime using Chicago’s 2013 mass school closure as a case study.[5] In addition to representing an important case deserving study in and of itself given its historic size, Chicago’smass closure offers several attractive methodological features, including the formation of a valid comparison group based on the schools considered but not selected for closure, the significant and unexpected shock of the closures on their communities due to inadequate community engagement during the district’s planning and execution of the closure process, and the five-year moratorium on school closures that the district instituted after 2013.

I used a monthly panel of crime counts between 2008 and 2018 in order to test the differential impact of school vacancy, repurposing, and merger on neighborhood crime. I collected crime incident data from Chicago’s online open data portal. The data include the type of crime as classified under the Uniform Crime Reporting Program, geographic location, and date of each crime. A total of 282,373 violent and 2,898,693 nonviolent crimes are included in the 10 years covered by the data.

I collected data on the 464 elementary schools open in the 2012–2013 school year from CPS. I then identified the 129 elementary schools initially considered for closure in February 2013 and the 49 that were ultimately voted for closure in May 2013. I also identified the 48 welcoming schools, linking them to the closed schools whose students they were welcoming and noting whether they relocated to another building. I established five post-closure status conditions: the school experienced no change (reference; 75.3 percent of schools); the school merged (8.4 percent); the school is vacant (10.4 percent); the school was repurposed into a non-school (3.1 percent); and the school was repurposed into a non-welcoming school (2.9 percent).

I constructed a panel data set containing monthly crime for the neighborhoods surrounding public elementary schools on the February 2013 list. My definition of a neighborhood was a circular buffer of radius r surrounding each elementary school. I tested several radii, specifically r = 75, 150, 300, and 450 meters. I then spatially joined crime data to each buffer.

Neighborhoods with Merged Schools Saw Biggest Rise in Nonviolent Crime

First, I found that merged school locations experienced an increase in nonviolent crime at the 75-meter scale. Second, I found that the increase, although declining in magnitude, persisted at the 150-meter (22 percent increase in crime) and 300-meter (4 percent) scales. These findings support arguments offered by teachers, students, parents, and public-school advocates that closures increase local crime through the merger of student populations. The persistence of the effect across larger distances suggested explanatory mechanisms such as commuting across gang boundaries that went beyond something about the area immediately surrounding the school. Third, I found an opposite effect (a 35 percent decrease in nonviolent crime) in the 75-meter areas surrounding schools that were vacant. However, this effect was not significant at larger spatial scales. Fourth, neighborhoods surrounding schools that were repurposed into a non-school experienced a 33 percent decrease in nonviolent crime. Similar to the vacancy effect, the decrease disappeared after the 75-meter radius.

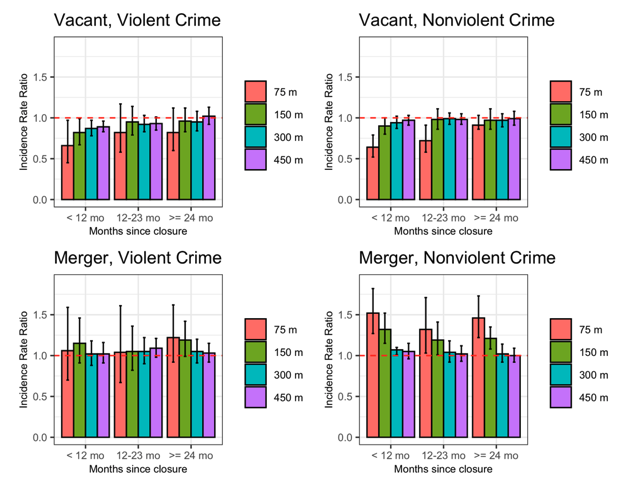

I also tested the persistence of the effects over time (Figure 1). There was a 34 percent decrease in violent crime in the first year in the 75-meter areas surrounding schools that were vacant. This negative effect was significant, but decreased in magnitude at larger spatial scales. I also found a decrease in nonviolent crime, but only at the 75-meter scale. This effect persisted after a year (36 percent decrease), becoming smaller in the second year (28 percent), and disappearing thereafter. These results indicate that the effects of vacancy on crime are not only spatially localized but short term.

Neighborhoods with merged schools experienced no change in violent crime across all time periods and buffer sizes (Figure 1). In contrast, I found a persistent increase in nonviolent crime across time at the 75-, 150-, and 300-meter scales. Nonviolent crime increased by 52 percent in the first year after merger at the 75-meter scale. This increase diminished in the second year (32 percent) but increased thereafter (46 percent). At the 150-meter scale, neighborhoods with a merged school experienced a 32 percent increase in nonviolent crime in the first year of merger. The increase was 18 percent and 20 percent in the second year and thereafter, respectively. I also found a persistent albeit smaller increase in nonviolent crime at the 300-meter buffer. Neighborhoods within 300 meters of a merged school experienced a 7 percent and 4 percent increase in nonviolent crime in the first and second year after merger, respectively. Overall, school merger exhibits more expansive spatiotemporal effects on nonviolent crime than building vacancy.

Figure 1

Analysis, Planning and Engagement All Essential

The results from my analysis carry several implications. First, contrary to claims made by opponents of school closures, building vacancy was associated with a decrease in local violent and nonviolent crime. I also found that nonviolent crime decreased when a school building was repurposed into a non-school. This decrease may be due to the removal of students from the area, who act as both potential offenders and victims of crime. This explanation makes sense since the effects were found only in the neighborhood surrounding the school and in the short term, persisting for less than two years for nonviolent crime and less than a year for violent crime. My results indicate that public officials should be proactive in repurposing closed school buildings, ideally establishing a plan well before schools officially close.

Second, I found that neighborhoods with schools that merged two or more student communities experienced an increase in nonviolent crime that persisted beyond one year across spatial scales. This suggests that the land use effects of school closure are spatiotemporally localized, whereas the student merger component has much broader community-wide consequences. Third, I found that closures impact not just the neighborhoods surrounding the schools that were officially closed but also the neighborhoods surrounding the non-closed schools that received displaced students. Taken as a whole, my findings suggest that the effects of closures are much wider than previously conceived. Policy makers and local officials conducting cost-benefit analyses of school closures should take these broader factors into account—especially given that such closures disproportionately affect disadvantaged and minority communities.

Noli Brazil is an Assistant Professor of Human Ecology at UC Davis.

References

[1] McFarland, Joel, Bill Hussar, Cristobal De Brey, Tom Snyder, Xiaolei Wang, Sidney Wilkinson-Flicker, Semhar Gebrekristos, Jijun Zhang, Amy Rathbun, Amy Barmer, Farrah Bullock Mann, Serena Hinz, Thomas Nachazel, Wyatt Smith, and Mark Ossolinski. 2017. “The Condition of Education 2017. NCES 2017-144.” National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2017144

[2] Wilson, James Q., and George L. Kelling. 1982. “Broken Windows.” Atlantic Monthly 249:29–38.

[3] Ahmed-Ullah, Noreen. 2013. “Gang Expert Testifies School Closings Will Put Kids in Line of Fire.” The Chicago Tribune, July 17. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2013-07-17-ct-met-cps-closings-hearings-20130717-story.html

[4] Gordon, Molly, Marisa de la Torre, Jennifer Cowhy, Paul Moore, Lauren Sartain, and David Knight. 2018. “School Closings in Chicago: Staff and Student Experiences and Academic Outcomes.” University of Chicago Consortium. https://consortium.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/2018-10/School%20Closings%20in%20Chicago-May2018-Consortium.pdf

[5] Brazil, Noli. 2020. “Effects of Public School Closures on Crime: The Case of the 2013 Chicago Mass School Closure.” Sociological Science. 7: 128-151.