Place-Based Improvement Programs Favor Gentrifying Neighborhoods Over Those Most in Need

By Noli Brazil and Amanda Portier, University of California, Davis

Place-based policies commonly target disadvantaged neighborhoods for economic improvement, typically in the form of job opportunities, business development or affordable housing. In an attempt to ensure that investment is channeled to truly distressed areas, place-based programs narrow the pool of eligible neighborhoods based on a set of socioeconomic criteria. These criteria, however, may not identify the places most in need. In a recent study, we examined the relationship between neighborhood gentrification status and eligibility for a range of place-based improvement programs. We found that large percentages of gentrifying neighborhoods were eligible for each of the four programs, with many neighborhoods eligible for multiple programs. In the case of one particular program, the probability of eligibility was nearly twice as high for gentrifying neighborhoods than not-gentrifying neighborhoods. To ensure that the places most in need of investment do not miss out on these programs, program officials and administrators should consider the gentrification status of neighborhoods and their adjacent neighborhoods as part of the selection and project-development process.

Key Facts

- Gentrifying neighborhoods were more likely to be eligible for investment than non-gentrifying areas in two of the four federal place-based programs we examined.

- The overlap between gentrification and eligibility was strongest for the Opportunity Zone program, with the odds of eligibility being nearly twice as high for gentrifying neighborhoods than not-gentrifying ones.

- Place-based programs should adapt their selection criteria to avoid favoring gentrifying neighborhoods over more socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Place-based approaches to community economic development, such as the federal Opportunity Zone (OZ) program rolled out in 2018, are intended to target low-income neighborhoods for economic and social reinvestment. However, the selection criteria used by such programs are unstandardized, rely on a on a narrow set of characteristics despite the multidimensionality of disadvantage, do not account for neighborhood change and are sometimes applied to out-of-date data.[1] These criteria may thus inadvertently grant eligibility to gentrifying neighborhoods, or neighborhoods adjacent to gentrifying neighborhoods, depriving areas in greater need of essential funding.

Given the potential negative consequences associated with gentrification—including the displacement of low-income residents, rising income inequality, and negative health effects among minority and economically vulnerable residents—place-based programs may thus fail to alleviate the problem they were intended to remedy: the spatial inequality of disadvantage.[2]

In our study, we examined the relationship between neighborhood gentrification status and eligibility for four federal place-based programs in 2018: New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), OZ, Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), and the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) program. Our goal was to understand to what extent gentrifying neighborhoods were eligible to receive place-based investment dollars that were needed more urgently elsewhere.

Examining the Relationship Between Gentrification Status and Eligibility for Federal Place-Based Investment

We began by compiling indicators of neighborhood eligibility for the NMTC, OZ, LIHTC, and CDFI programs in 2018. These were based on various sources (for example, 2011-2015 American Community Survey data) and included such criteria as a poverty rate of at least 20% and an unemployment rate 1.5 times the national average. We then established four variables for assessing the gentrification status of a given neighborhood: household income, housing value, gross rent, and college-educated residents. We used these variables to analyze the change from 2000 to 2014–2018 to determine neighborhood gentrification status in 2018. With these data in hand, we ran a series of multivariate regression models to examine the relationship between program eligibility and gentrification status.

Gentrifying Neighborhoods More Eligible for Selective Investment Than Areas More in Need

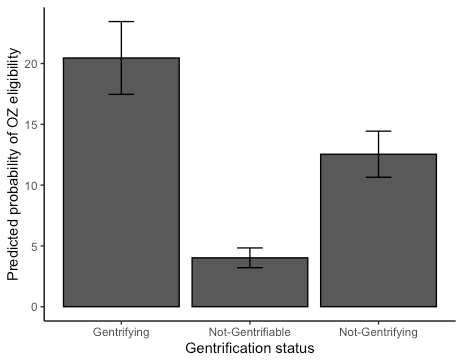

In our descriptive analysis, we found that large percentages of not-gentrifying neighborhoods were eligible for all programs, in particular the CDFI (86.8 percent) and NMTC (89.4 percent). However, non-trivial percentages of gentrifying neighborhoods were also eligible, with approximately two-thirds of gentrifying neighborhoods eligible for CDFI and NMTC, followed by 36.1 percent for LIHTC and 20.8 percent for OZ. While 86.5 percent of not-gentrifying neighborhoods were eligible for at least two programs, nearly two-thirds of gentrifying neighborhoods were eligible for multiple programs. Notably, while the likelihood of a gentrifying neighborhood being eligible for LIHTC, CDFI, and NMTC was much smaller compared to a not-gentrifying neighborhood, it was nearly equal for OZ (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Predicted probability of OZ eligibility by gentrification status.

When accounting for neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics, our multivariate analysis revealed that the odds of eligibility for the NMTC and CDFI programs was 0.8 times lower for gentrifying neighborhoods relative to not-gentrifying neighborhoods. The probability of LIHTC eligibility was the same across gentrifying and not-gentrifying neighborhoods. In contrast, the odds of OZ eligibility were 1.8 times higher for gentrifying neighborhoods than not-gentrifying neighborhoods. Here, the probability that a gentrifying neighborhood was eligible for the OZ program was 20.5 percent. This was higher than the probabilities for not-gentrifying (12.5) and not-gentrifiable (4.0). We also found that, with the exception of the CDFI program, the probability of eligibility increased with a greater percentage of adjacent neighborhoods experiencing gentrification.

Place-Based Programs Must Be More Selective to Avoid Investing in Gentrifying Neighborhoods

Going forward, policymakers and place-based program officials and administrators should explicitly account for neighborhood socioeconomic changes in the neighborhood selection and project-development process. In addition to incorporating change over time in the eligibility criteria, the most up-to-date ACS data should be used to determine which neighborhoods are experiencing recent socioeconomic improvement. Furthermore, program officials should engage with gentrification more directly—for instance, by categorizing eligibility by neighborhood type rather than treating neighborhoods as homogeneously high- or low-opportunity, and by incentivizing projects designed to mitigate the negative consequences of gentrification.[3] For example, LIHTC funding in gentrifying neighborhoods may mitigate the displacement effects of gentrification by increasing the supply of affordable housing.

Programs should also consider the gentrification status of nearby neighborhoods. On the one hand, directing investment to neighborhoods near gentrifying areas might reduce local inequalities if they are economically isolated. On the other hand, neighborhoods next to gentrifying areas may already be at risk of gentrifying, and investment with no guard rails will tip them toward gentrification, further spatially concentrating capital within a city.[4]

Although the overlap between eligibility and gentrification was present across all four programs, it was strongest for OZ. While OZ neighborhoods are poor and low-income on average, many of the selected neighborhoods have structural advantages, including undergoing positive socioeconomic changes.[5] As such, future improvement in gentrifying OZ neighborhoods will be misattributed to the program when instead it may be driven by preexisting positive socioeconomic trends. Furthermore, this program’s eligibility process and investment structure make it susceptible to the types of project development that may reinforce the negative consequences of gentrification.[6] To help avoid these consequences, some selection guard rails in addition to the poverty threshold should be followed, as is already done in the NMTC and CDFI programs.

Moreover, not only should additional indicators of economic distress be incorporated into the program’s qualifying criteria, but also changes in these indicators over time. Given that it is the most recent large-scale economic development program—one with the potential for being the largest in U.S. history—the OZ program warrants serious future investigation in terms of what projects are developed and the impact of those projects on community well-being.

Explore the Neighborhood Investment Project app.

Noli Brazil is an assistant professor of human ecology at the UC Davis.

Amanda Portier is a recent graduate of UC Davis and recipient of the University Medal for excellence.

References

1. Galster, George. 2019. Making our Neighborhoods, Making our Selves. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press.

2. Christafore, David, and Susane Leguizamon. 2019. “Neighbourhood Inequality Spillover Effects of Gentrification.” Papers in Regional Science 98 (3): 1469-84. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12405

3. Brazil, N., Wagner, J., & Ramil, R. (2022). Measuring and mapping neighborhood opportunity: A comparison of opportunity indices in California. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science. doi.org/10.1177/23998083221129616

4. Guerrieri, Veronica, Daniel Hartley, and Erik Hurst. 2013. “Endogenous Gentrification and Housing Price Dynamics.” Journal of Public Economics 100: 45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.02.001

5. Frank, Mary Margaret, Jeffrey L. Hoopes, and Rebecca Lester. 2020. “What Determines Where Opportunity Knocks? Political Affiliation in the Selection of Opportunity Zones. Political Affiliation in the Selection of Opportunity Zones.” Accessed October 19, 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3534451

6. Layser, Michelle D. 2019. “The Pro-Gentrification Origins of Place-Based Investment Tax Incentives and a Path Toward Community Oriented Reform.” Wisconsin Law Review 2019 (5): 745–817.