Parenting Aggravation Associated with Food Insecurity Impacts Children’s Behavior and Development

By Kevin Gee and Minahil Asim, UC Davis

Parents struggling with food insecurity can experience heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. These pressures may negatively affect their parenting, which may in turn affect the behavior of their children. In this study, we investigated the parenting aggravation levels of parents who experienced food insecurity in the aftermath of the Great Recession. We also explored the extent to which such aggravation may be responsible for the link between food insecurity and children’s behaviors. We found that parents of first-graders who became food-insecure had increased levels of parenting aggravation. We also detected negative effects of parental aggravation on children’s executive functioning—that is, on their attentiveness and ability to control themselves. As such, we recommend supporting food-insecure parents, not just by stabilizing their access to food, but with broader psycho-social support.

Key Facts

- Parents struggling with food insecurity can experience heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression.

- Parenting aggravation that coincides with food insecurity is negatively associated with children’s executive functioning.

- Supporting food-insecure parents may improve parenting and thus have benefits both for parents and their children.

Food insecurity can take an emotional toll on parents. The inadequacy that parents can feel as they struggle to provide food for their families can lead to stress, anxiety, and depression.[1] Food insecurity can also lead to parental irritability and anger.[2] What’s more, the negative consequences of food insecurity on parents’ wellbeing can in turn influence the wellbeing of their children, putting their behavioral development at risk.[3]

Financial strain forces families to confront economic pressures, including the inability to fulfill basic needs such as sufficient food and housing. The psychological distress caused by these kinds of economic pressures not only strains the relationship between parents, but can also lead to diminished mother-child interaction and suboptimal parenting practices. Such circumstances have a direct negative impact on children’s behavioral development.[4] For example, heightened parental depression and anxiety prompted by food insecurity has been linked to aggressiveness, anxiety and hyperactivity in three-year-olds.[5]

With all this in mind, we set out to answer two specific research questions. First, how does food insecurity, as experienced by parents, relate to their own levels of parenting aggravation? Second, does parenting aggravation contribute to the relationship between adult food insecurity and children’s executive functioning and behavior problems?

Measuring Aggravation and Its Impact

For this study we drew on the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 2010-11, a large-scale, nationally representative sample of approximately 18,200 children across the US who entered kindergarten in fall 2010. We focused on the spring of kindergarten and first grade. This dataset offered a range of robust measures for both parents and their children, including adult food insecurity, parenting aggravation, children’s scores on behavioral assessments, and a rich set of parental and child characteristics.

To address our first research question, we used the Aggravation in Parenting Scale that was administered as part of the 2011 parent interview. Parents indicated how often and how acutely they felt that: (1) being a parent was harder that they thought; (2) their child did things that really bothered them; (3) they gave up more of their life to meet their child’s needs; and (4) they felt angry with their child.

For the second question, we matched individuals using characteristics documented in spring of their child’s kindergarten year. These included demographics and key predictors of food insecurity: food stamps in the past 12 months, number of places a child lived before birth, access to medical care, parental income, and so on. Meanwhile, to measure children’s executive functioning, we used scores reported by children’s teachers on the 12-item Children’s Behavior Questionnaire.

Clear Negative Consequences

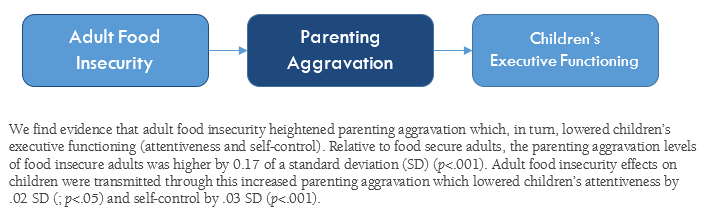

Among parents raising young children in the aftermath of the Great Recession, we found that adult food insecurity had negative consequences on parenting. In particular, parents who were previously food secure, but later became food insecure, experienced higher levels of parenting aggravation. By focusing on parents who change from food secure to food insecure, we are better able to isolate the effect of food insecurity on both parental aggravation and children’s functioning. This directly links the source of parents’ distress in the wake of food insecurity to their own experience of such conditions.

We also found that parenting aggravation contributed significantly to the relationship between parents’ food insecurity and their children’s behavioral outcomes. Such aggravation, our study suggests, also negatively affects children’s executive functioning, reducing their ability to pay attention and compromising their self-control. Because executive function may be related to children’s ability to succeed in school settings, this reduced functioning can have serious consequences for affected children.

Greater Support is Needed

Our study underscores the importance of addressing food insecurity from a broader, family-system perspective. Beyond its nutritional dynamics, food insecurity influences the behaviors of both parents and children. What’s more, its impact on parental well-being can in turn influence parent-child interactions, which are core drivers of children’s development.

Given our findings, we suggest strengthening support for parents experiencing stress caused by food insecurity. This is especially important for vulnerable groups such as single mothers from low-income backgrounds, who disproportionately bear the brunt of food insecurity. Supporting food-insecure parents—by stabilizing their access to food, but also with broader psycho-social support—may ultimately have benefits for both parents and their children.

Kevin Gee is an Associate Professor of Education at UC Davis.

Minahil Asim is a PhD candidate in education policy at UC Davis.

References

[1] Dunifon, R., & Kowaleski-Jones, L. (2003). The influences of participation in the national school lunch program and food insecurity on child well-being. Social Service Review, 77(1), 72-92.

[2] Hamelin, A.-M., Habicht, J.-P., & Beaudry, M. (1999). Food insecurity: consequences for the household and broader social implications. The Journal of Nutrition, 129(2), 525S-528S.

[3] Gershoff, E. T., Aber, J. L., Raver, C. C., & Lennon, M. C. (2007). Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Development, 78(1), 70-95.

[4] Ashiabi, G. S., & O’Neal, K. K. (2008). A framework for understanding the association between food insecurity and children’s developmental outcomes. Child Development Perspectives, 2(2), 71-77.

[5] Whitaker, R. C., Phillips, S. M., & Orzol, S. M. (2006). Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children. Pediatrics, 118(3), 859-868.