Household Food Insecurity Associated with Decline in Attentional Focus of Young Children with Disabilities

By Kevin A. Gee, University of California, Davis

The potential ramifications of food insecurity for the development of children with disabilities are often overlooked in broader policy discussions, despite the fact that such ramifications are likely more significant for these children. In a recent study, I investigated how food insecurity relates to the behavioral outcomes of young school-aged children with disabilities across the first two years of their elementary education. Overall, I found that household food insecurity was related to a significant decline in children’s attentional focus. Further, children in families who transitioned out of food insecurity and became food-secure experienced gains in attentional focus and inhibitory control. My findings offer compelling evidence about food insecurity’s consequences for developmental outcomes. They also identify targets of opportunity for support and intervention—aimed both at children with disabilities and at the families and caregivers responsible for their well-being.

Key Facts

- Families raising children with disabilities experience higher rates of food insecurity than families raising children without any special needs.

- In my study, among children with disabilities, household food insecurity was related to a significant decline in attentional focus.

- Transitioning out of household food insecurity into food security was associated with significant gains in attentional focus and inhibitory control.

Food insecurity is one of many pathways through which the cascading influences of economic hardship can ultimately impact children’s outcomes. Psychological distress resulting from financial strain leads to compromised interactions between children, parents and caregivers, which can in turn negatively influence children’s developmental outcomes. This kind of financial strain and psychological distress has been shown to be more acute among families raising children with disabilities than among families with children that do not have disabilities.[1]

In the US, approximately 7.1 million children aged 3–21 have disabilities qualifying them for special education services.[2] Families raising children with disabilities experience higher rates of food insecurity, with the difference ranging from about 4.7 percent to 11 percent.[3,4] Studies have shown that families raising children with special needs, relative to families with children without special needs, experience an increased probability of worrying that food will run out, running out of food, and skipping meals due to lack of money.[5] Reasons for this can include increased medical costs, time allocated toward caring for children with complex needs, and finally, the stress of caring for children with specialized needs.

In my study, I set out to explore the association between household food insecurity and the developmental outcomes of children with disabilities.[6] To do this, I examined how household food insecurity relates to children with disabilities’ executive functioning and problem behaviors.

Estimating the Effects of Food Insecurity

To conduct my analysis, I used data on approximately 1420 children with a disability from the restricted -use version of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey, Kindergarten Class of 2010–2011. I used two measures respectively capturing children’s executive functioning (attentional focus and inhibitory control) and problem behaviors (externalizing and internalizing) in the spring of kindergarten and first grades. My assessment of a household’s food insecurity status was based on the USDA’s 18-item Household Food Security Survey Module. To estimate how household food insecurity is associated with outcomes of children with disabilities, I leveraged changes in the incidence of household food insecurity between the spring of kindergarten and first grade using a first-difference regression model.

Household Food Insecurity Related to A Decline in Attentional Focus

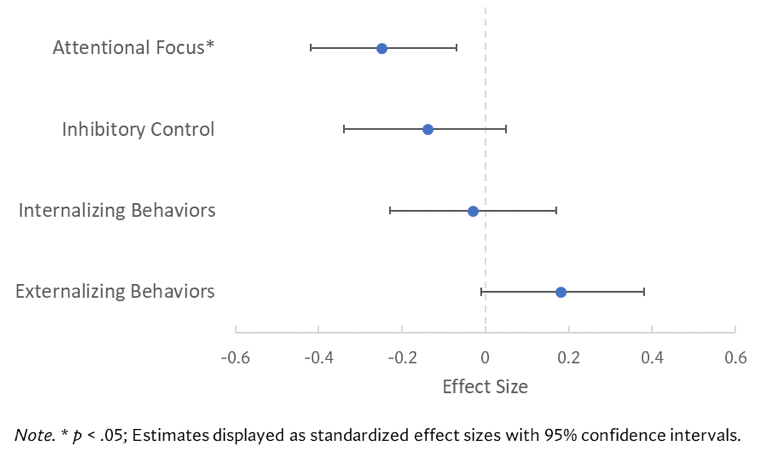

Among children with disabilities, I found that household food insecurity was related to a significant decline in attentional focus of approximately .25 of a standard deviation (SD). I also identified a decline in inhibitory control (-0.14 SD) and an increase in externalizing problem behaviors (0.18 SD), though neither of these relationships significantly differed from zero. The effect on internalizing problem behaviors was, unexpectedly, a decline of 0.03 SD (though this estimate too was not significantly different from zero). For comparison, household food insecurity among children without disabilities was unrelated to attentional focus. For these children, as for children with disabilities, food insecurity was also unrelated to inhibitory control as well as internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

I also looked at the effects of transitions into and out of food insecurity. Children from households who exited food insecurity experienced a gain in their attentional focus (0.35 SD) and inhibitory control (0.27 SD). However, for children without disabilities, neither type of transition related significantly to internalizing or externalizing behaviors.

Figure 1: Estimates of the relationship between household food insecurity and developmental outcomes of children with disabilities. Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 2010–2011 (ECLS-K: 2011) Restricted-Use Kindergarten-Second Grade Data File.

Strengthen Supports for Families Raising Children With Disabilities

My study shows how food insecurity is negatively associated with the behavioral outcomes of children with disabilities. It also shows how transitions out of food insecurity can be especially beneficial for children’s outcomes. Among families raising a child with a disability in kindergarten, food insecurity was related to lower attentional focus. Not all developmental outcomes—especially children’s internalizing or externalizing problem behaviors—were affected by food insecurity; this may be because food insecurity’s effect may be indirectly transmitted onto children’s outcomes via key mechanisms, such as parenting aggravation, which can in turn exert influence on certain outcomes, but not others.[7]

Children with disabilities raised in homes that became food secure experienced higher attentional focus and inhibitory control skills. These findings suggest that the children who are raised by families that were able to successfully overcome food insecurity—and possibly, the uncertainty, stress, and anxiety in the wake of food insecurity—can benefit developmentally from transitioning into a more food-secure environment.

For practice and policy, these results underscore the need to ensure that supports—especially broader strategies to tackle the root causes of food insecurity such as alleviating economic pressures—are made available and targeted to families raising children with disabilities. Such supports and interventions could improve family functioning and, subsequently, help buffer families from stress and anxiety brought on by economic pressures like food insecurity. Helping caregivers of children with disabilities to manage both precipitating and perpetuating factors of food insecurity, such as stressors within the home, may be an important first step.

Fortunately, there are several available mechanisms to counteract food insecurity head-on by leveraging our public education and social service sectors. For example, offering the National School Breakfast Program has shown to cause reductions in the probability that a child will experience very low food insecurity.8 Further, linking caregivers to important safety net services like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children may not only mitigate the incidence of food insecurity but may buffer its potentially harmful effects on children. Strengthening supports aimed at families raising children with disabilities may not only address underlying factors leading to food insecurity, thereby promoting overall family health and wellness; it may also have critical implications for improving the developmental well-being for children under their responsibility and care.

Kevin A. Gee is an associate professor of education at UC Davis.

References

[1] Goudie, A., Narcisse, M.-R., Hall, D. E., & Kuo, D. Z. (2014). Financial and psychological stressors associated with caring for children with disability. Families, Systems, & Health, 32, 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000027

[2] National Center for Education Statistics. (2020, May). Students with disabilties. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg/students-with-disabilities

[3] Rose-Jacobs, R., Goodhart Fiore, J., Ettinger de Cuba, S., Black, M., Cutts, D. B., Coleman, S. M., … Frank, D. A. (2016). Children with special health care needs, supplemental security income, and food insecurity. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 37, 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1097/dbp.0000000000000260

[4] Adams, E. J., Hoffmann, L. M., Rosenberg, K. D., Peters, D., & Pennise, M. (2015). Increased food insecurity among mothers of 2-year-olds with special health care needs. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19, 2206–2214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1735-9

[5] Parish, S. L., Rose, R. A., Grinstein-Weiss, M., Richman, E. L., & Andrews, M. E. (2008). Material hardship in US families raising children with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 75, 71–92.

[6] Gee, K.A. (2021). The Consequences of Food Insecurity for Children with Disabilities in the Early Elementary School Years. In: Fiese, B.H., Johnson, A.D. (eds) Food Insecurity in Families with Children. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74342-0_3

[7] Gee, K. A., & Asim, M. (2019). Parenting while food insecure: Links between adult food insecurity, parenting aggravation, and children’s behaviors. Journal of Family Issues, 40, 1462–1485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513×19842902

[8] Fletcher, J. M., & Frisvold, D. E. (2017). The relationship between the school breakfast program and food insecurity. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 51, 481–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12163