Greater Resources Required to Protect People Experiencing Homelessness from COVID-19

By Ryan Finnigan, UC Davis

While the spread of the novel coronavirus is affecting different regions and populations to different extents, one thing is clear: people experiencing homelessness are especially susceptible to both the virus and the disease it can cause (COVID-19). This is due in part to the high concentration of people experiencing homelessness in urban and coastal regions with high infection rates. It is also true that, compared to the general population, people experiencing homelessness suffer from more health conditions and are less able to access health care. With outbreaks occurring in homeless shelters across the US, significant investment is needed urgently to protect this vulnerable group.

Key Facts

- People experiencing homelessness have a heightened vulnerability to the COVID-19 disease due to higher rates of other health conditions and inadequate access to health care, sanitation services, and physical distancing.

- Several outbreaks of the virus that causes COVID-19 have recently been documented in homeless shelters across the country.

- Providing adequate shelter space for the population experiencing homelessness while following CDC guidance for physical distancing could cost an additional $11.5 billion.

People experiencing homelessness have a heightened vulnerability to the COVID-19 disease, which is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, or “the coronavirus.” Currently, insufficient resources are devoted to reducing this risk. The scale of this problem is large. On a single night in January 2019, teams around the United States counted 567,715 people experiencing homelessness, and less than two-thirds of this population was in some form of temporary shelter.[1] This number is surely an underestimate; the total number of people experiencing homelessness at some point throughout the year may be three times as high.[2] The population experiencing homelessness is concentrated in urban areas and coastal states, relative to national population. About half of the population experiencing homelessness lives in California, Florida, and New York, all states with high numbers of people with COVID-19.

Relative to the housed population, people experiencing homelessness commonly have health conditions that increase the risk of the COVID-19 disease. Compared to the general population, people experiencing homelessness have substantially higher rates of disability, infectious diseases, and chronic diseases. The average age of people experiencing homelessness is higher than the national average, and chronic homelessness accelerates age-related physical declines.[3] In addition to greater need for health services, people experiencing homelessness also have lower access to health care and healthy behaviors (e.g., healthy eating, sufficient sleep) than the general population.

Potential Impacts of COVID-19

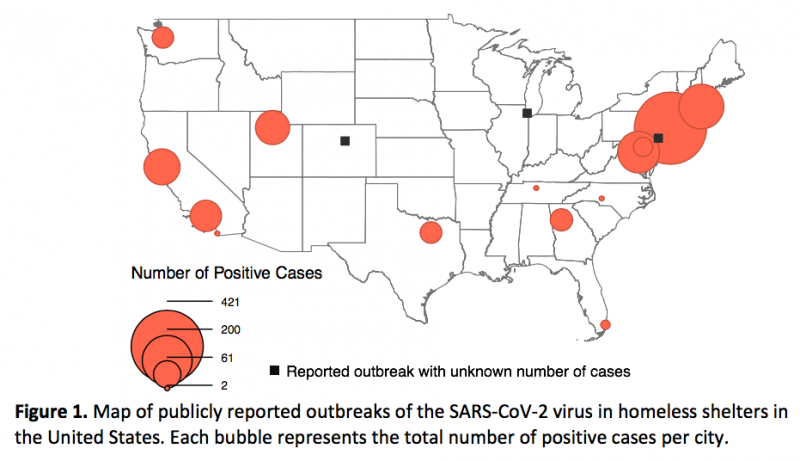

The risk of the COVID-19 disease for people experiencing homelessness is shaped by location. Early in the spread of the pandemic, many local governments focused on the heightened risk for people living in tent encampments. Tent encampments in urban areas are often densely populated and lack access to sanitation services.[4] As the pandemic spread, concern increased for residents of homeless shelters. The risk of infection by the SARS-CoV-2 virus is particularly high in congregate-living places such as nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, prisons and jails, and immigrant detention centers. A recent report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documented large outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 at homeless shelters in Boston, San Francisco, and Seattle. News reports have described further clusters of positive cases in homeless shelters around the country. For this policy brief, I assembled data from CDC reports and news stories on these clusters of SARS-CoV-2 infections, defined as two or more positive results per shelter. Figure 1 maps these shelter outbreaks, where the size of each bubble represents the total number of positive cases per city.

Systematic data on COVID-19 in homeless shelters, and especially in encampments, is generally unavailable, however. Widespread testing for the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been largely unavailable. The data presented in Figure 1 are further limited to outbreaks that are publicly reported by local news outlets. Due to these limitations, the spread of COVID-19 among people experiencing homelessness is surely vastly understated at this time.

In a recent study, researchers projected potential impacts of widespread SARS-CoV-2 infections for people experiencing homelessness. The study estimated that over 20,000 people could require hospitalization, over 7,000 could require critical care, and almost 3,500 could die due to COVID-19. These impacts would be particularly pronounced in cities like Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco.[5]

Interventions and Recommendations

To limit the spread of COVID-19, the CDC has issued several recommendations for homeless shelters. These recommendations include increasing sanitation, providing personal protective equipment for staff, and limiting visitors. The guidance also recommends that shelters provide quarantine and isolation sites for people testing positive for COVID-19 or experiencing symptoms, and maintain at least six feet of space between beds. The guidance also emphasizes the importance of continued service provision for people experiencing homelessness. It advises against closing shelters or turning away potentially infected clients.[6]

However, many shelters are unable to implement all of the CDC’s recommendations. News reports show that some shelters have reduced their capacities in order to implement physical distancing. Some shelters with outbreaks have also closed or stopped accepting new residents.[7]

Given shelters’ constraints and their heightened risks of COVID-19 infection, many people experiencing homelessness have moved into or remained in tent encampments. The CDC has recommended that local governments stop clearing tent encampments—a common practice prior to the pandemic[4]—and work to provide sanitation services, including restrooms and handwashing facilities. News reports indicate mixed implementation of these measures. A recent study projected that sheltering the population experiencing homelessness while following CDC guidance would require an additional $11.5 billion.[5]

Some state and city governments, like those in New York City and the states of California and Louisiana, have begun or expanded programs for sheltering high-risk people experiencing homelessness in private hotel rooms. These programs typically target people experiencing COVID-19 symptoms or those deemed to be at high risk due to other health conditions or advanced age. However, these programs have very low capacity relative to the population experiencing homelessness. For example, California has so far secured 10,974 hotel rooms and 1,133 trailers but has over 100,000 people experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Also, many organizations, including the White House’s Interagency Council on Homelessness, have resisted such programs due to their cost.[7]

Local governments and organizations serving people experiencing homelessness will continue to tailor their responses to their specific situations. The expanded shelter capacity, sanitation services for tent encampments, and/or private hotel rooms required for these responses require significantly greater resources than have previously been available. Given the many hardships faced by people experiencing homelessness, and their heightened vulnerability to COVID-19, such resources are desperately and urgently needed.

Ryan Finnigan is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at UC Davis.

References

[1] Meghan Henry et al., “The 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress” (Washington, D.C.: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2019)

[2] Marybeth Shinn and Jill Khadduri, In the Midst of Plenty: Homelessness and What to Do About It(Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2020)

[3] Seena Fazel, John R Geddes, and Margot Kushel, “The Health of Homeless People in High-Income Countries: Descriptive Epidemiology, Health Consequences, and Clinical and Policy Recommendations,” Lancet384, no. 9953 (October 25, 2014): 1529–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

[4] Zoe Loftus-Farren, “Tent Cities: An Interim Solution to Homelessness and Affordable Housing Shortages in the United States,” California Law Review99, no. 4 (2011): 1037–81

[5] Dennis Culhane et al., “Estimated Emergency and Observational/Quarantine Capacity Need for the US Homeless Population Related to COVID-19 Exposure by County; Projected Hospitalizations, Intensive Care Units and Mortality” (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2020), https://endhomelessness.org/resource/estimated-emergency-and-observational-quarantine-bed-need-for-the-us-homeless-population-related-to-covid-19-exposure-by-county-projected-hospitalizations-intensive-care-units-and-mortality/

[6] CDC, ““Interim Guidance for Homeless Service Providers to Plan and Respond to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19),” April 21, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/homeless-shelters/plan-prepare-respond.html

[7] Sarah Holder and Kriston Capps, “No Easy Fixes as Covid-19 Hits Homeless Shelters,” Citylab, April 17, 2020, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2020/04/homeless-shelter-coronavirus-testing-hotel-rooms-healthcare/610000/