De Facto Deported Children in Mexico Face Socioeconomic Disadvantage

By Erin Hamilton, UC Davis, Claudia Masferrer, El Colegio de México, and Paola Langer, UC Davis

Between 2000 and 2015, as the U.S. deported unprecedented numbers of Mexican immigrants, the population of U.S.-born children living in Mexico doubled in size. In a recent study, using data collected in 2014 and 2018 by the Mexican National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID), we estimated the number of de facto deported children. De facto deported children are U.S.-born children who emigrated to Mexico from the U.S. to accompany a deported parent.

We found that about one in six (or 80,000-100,000) U.S.-born children living in Mexico in 2014 and 2018 were there because the U.S. government deported one or both of their parents. We also found that de facto deported U.S.-born children were socioeconomically disadvantaged in Mexico compared to U.S.-born children whose parents migrated to Mexico for other reasons. Our analysis showed too that women were over-represented among deported people who brought their U.S.-born children to Mexico. When deported mothers brought their children, they were far less likely to do so with a partner than were deported fathers.

When redesigning immigration and child welfare policies, U.S. policymakers should consider the interests of U.S.-citizen children forced to live abroad.

Key Facts

- One in six U.S.-born children living in Mexico in 2014 were de facto deported, meaning they emigrated from the United States to Mexico to accompany one or more deported parents.

- Women are over-represented among deported parents with U.S.-born children in Mexico, and deported mothers in Mexico are far less likely to live with a partner than deported fathers.

- De facto deported U.S.-born children in Mexico experienced greater socioeconomic disadvantage than those whose families migrated for other reasons.

Background

The first two decades of the 21st century recorded the largest number of deportations in U.S. history.[1] When the U.S. government deports the parent of a child living in the U.S., there are three possibilities for family reorganization. First, the child may remain in the U.S., and thus be separated from the deported parent.[2] Second, the parent may re-enter the U.S., a common strategy despite possible criminal penalties.[3] Third, the child may immigrate to the parent’s country of origin, and thus experience de facto deportation.[4] The de facto deportation of young U.S. citizens results in the physical and social separation between them and the U.S. institutions and social systems designed to care for, educate, and support them.

U.S. immigration enforcement disproportionately targets Latino men.[5] However, traditional gender roles, in which women are expected to adopt the role of in-person caregiver, and gendered patterns of family migration led us to expect women to be over-represented among deported people who returned with children. Accordingly, in our study, we examined gendered differences in the presence of U.S.-born children in the households of women and men who were deported, as well as in whether the deported parent was accompanied by or lived with a partner following deportation.[6] We also sought to find out how de facto deported U.S.-born children in Mexico fared in terms of various indicators of social wellbeing.

Examining De Facto Deportation

We used data from the 2014 and 2018 waves of the ENADID, a nationally-representative, cross-sectional survey of about 100,000 households conducted on a recurring basis by the Mexican National Institute of Statistics and Geography. Designed to understand demographic processes—especially fertility and reproductive behavior, infant mortality, and migration—in Mexico, the ENADID is collected in person in the fall of each survey year. In 2014, the survey added a new question about the reason for migration to Mexico, which includes deportation as a possible reason. We identified de facto deported U.S.-born children as recent migrant U.S.-born children living in a household with at least one recent migrant parent who reported that their reason for return was deportation.

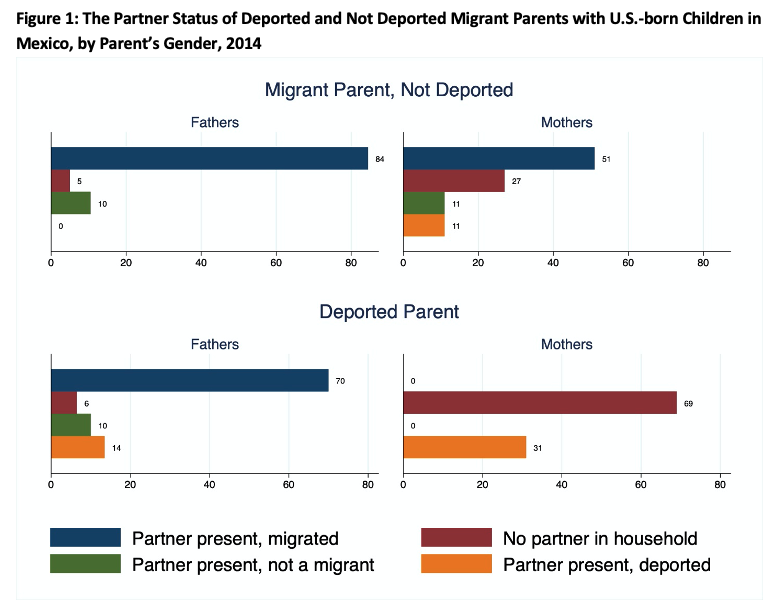

To explore the gendered nature of de facto deportation, we compared the partner status of recent migrant mothers and fathers who were not deported and who were deported to consider how gender and family structure interact with different processes of migration to Mexico.

To explore social wellbeing among de facto deported children, we used the 2014 ENADID to compare de facto deported U.S.-born children to recent migrant U.S.-born children with recent migrant parents who reported reasons other than deportation for their return. We also compared these two groups of U.S.-born children to all Mexican-born children. We compared children on demographic characteristics and child wellbeing measures including school attendance, disability, health insurance, the presence of both parents in the household, and household poverty indicators.

De Facto Deported Children Face Family Separation and Socioeconomic Disadvantage

There were 1,865 and 1,945 U.S.-born children counted in the 2014 and 2018 ENADIDs, respectively. These U.S.-born children counted in the survey represented over half a million U.S.-born children living in Mexico in those years. Among recent-migrant U.S.-born children whose parents are also recent migrants, 73 were de facto deported in 2014, and 28 in 2018. These samples represented 23,918 U.S.-born recent migrant de facto deported children living in Mexico in 2014 and 8,309 in 2018. In both years, approximately one out of every six U.S.-born children who were recent migrants with recent-migrant parents living in Mexico was de facto deported from the U.S. When we apply the rate of de facto deportation among recent migrant children with recent migrant parents to the entire population of U.S. born children living in Mexico, we estimate that as many as 100,000 U.S. born children in Mexico in 2014 and 80,000 in 2018 were de facto deported.

Figure 1 shows results regarding the gendered nature of de facto deportation. Among recent migrant parents living with U.S.-born children in Mexico, fathers and mothers who were not deported most frequently lived with a partner who also migrated, suggesting a process of nuclear family migration. Nuclear family migration is also the norm for deported fathers, 70 percent of whom live with a recent-migrant partner who was not deported. One in ten recent-migrant mothers who were not deported lived with a recently deported partner, suggesting they were de facto deported like their U.S.-born children. The large majority (69 percent) of deported mothers, on the other hand, do not live with a partner in Mexico. No deported mothers in the 2014 ENADID sample were accompanied by migrant partners who were not themselves deported.

Regarding the wellbeing of de facto deported children, we found that recent-migrant children of recent-migrant parents were far more likely than non-migrant children to live in a single-parent household (29-30 percent vs. 18 percent). More than half of recent migrant U.S.-born children in Mexico lacked health insurance coverage, with the rate highest among de facto deported children (70 percent, compared to 53 percent of children who migrated for reasons other than deportation). By comparison, 15 percent of Mexican-born children lacked health insurance. De facto deported U.S.-born children were two times more likely to live in precarious housing than U.S.-born children who migrated for other reasons (16 percent vs. 8 percent) and 75 percent more likely to live with few basic services in the household (14 percent vs. 8 percent).

Focus on Child and Family Welfare

We estimated that 98,557 U.S.-born children were living in Mexico in 2014 because they migrated to accompany a deported parent. In 2018, that number was 83,262. This means that about one in six U.S.-born children living in Mexico in these years were there because the U.S. government deported one or both of their parents. We found strongly gendered patterns that interact with deportation to inform distinct household structures for recent-migrant U.S.-born children in Mexico. Specifically, we found that the U.S. deportation regime places disproportionate burdens on deported mothers, who are far more likely than deported fathers to live in Mexico with U.S.-born children without a co-resident partner. We also found that de facto deported U.S.-born children in Mexico in 2014 experienced greater socioeconomic disadvantage than U.S.-born children whose families migrated for reasons other than deportation. For instance, they were more likely to lack health insurance and to face precarious housing conditions.

The U.S. government has forced de facto deported children to live outside their country of citizenship to remain with their parents. Our research suggests that, in doing so, it exposes such children to disadvantages unique to their circumstances. The U.S. government should increase the effort it makes to take care of its young citizens, regardless of their parents’ immigration status or the child’s country of residence.[7] Binational programs should focus on child and family welfare to improve the lives of U.S. citizens whom the U.S. government forces to reside elsewhere.

Erin R. Hamilton is a professor of sociology at the University of California, Davis.

Claudia Masferrer is an associate professor at the Center for Demographic, Urban, and Environmental Studies at El Colegio de México.

Paola Langer is a PhD candidate at the University of California, Davis.

This policy brief was produced in collaboration with the UC Davis Global Migration Center.

Leer en español vía MIGDEP.

This work has been supported by the Russell Sage Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation of New York under Grant 2011-29160; the UC Davis Academic Senate; and the Seminar on Migration, Inequality, and Public Policies (MIGDEP) from El Colegio de México. Any opinions expressed are those of the principal investigators alone and should not be construed as representing the opinions of the funders.

References

[1] Department of Homeland Security. 2018. “Yearbook of Immigration Statistics.” https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook/2018.

[2] Amuedo‐Dorantes, Catalina, and Esther Arenas‐Arroyo. 2019. “Immigration Enforcement and Children’s Living Arrangements.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 38 (1): 11–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22106.

[3] Vargas Valle, Eunice D., Erin R. Hamilton, and Pedro P. Orraca Romano. 2022. “Family Separation and Remigration Intentions to the USA among Mexican Deportees.” International Migration 60 (3): 139–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12905.

[4] Zayas, Luis H. 2015. Forgotten Citizens: Deportation, Children, and the Making of American Exiles and Orphans. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

[5] Golash-Boza, Tanya, and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2013. “Latino Immigrant Men and the Deportation Crisis: A Gendered Racial Removal Program.” Latino Studies 11 (3): 271–92. https://doi.org/10.1057/lst.2013.14.

[6] Hamilton, Erin R., Claudia Masferrer and Paola Langer.2022. “U.S. Citizen Children De Facto Deported to Mexico.” Population and Development Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12521

[7] Masferrer, Claudia, and Luicy Pedroza. 2021. “The Intersection of Foreign Policy and Migration Policy in Mexico Today.” Mexico City: Colegio de Mexico. https://migdep.colmex.mx/publicaciones/foreign-migration-policy-report.pdf.