Missed Housing and Utility Payments Are Common and Persistent in the United States

By Ryan Finnigan and Kelsey D. Meagher, UC Davis

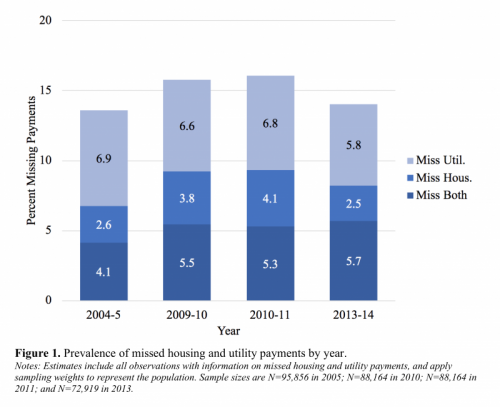

Housing and utility costs consume the majority of monthly incomes for millions of individuals and families in the United States. Missed payments can result in penalties, utility shutoffs, and evictions. Between 14 and 16 percent of the U.S. population experiences utility and/or housing hardship each year, defined as the inability to make full and on-time payments anytime in the past year.[1] Our study found that utility hardship is more common and persistent than housing hardship, which suggests that it is a more durable form of deprivation. Households that experience only utility hardship are notably more disadvantaged than those with only housing hardship. We also found that poor health is the strongest predictor of both hardships.

Utility and Housing Hardship Are Common in the U.S.

Nearly 40 percent of Americans experience material hardship, meaning that they struggle to meet at least one basic need (such as housing, food, utilities and healthcare). Research shows that many low-income households juggle different basic needs. For example, some will choose to forgo utility payments to keep up with rental or mortgage payments.[2] While food insecurity is the most common hardship, housing and utility hardships are also common, and missing these payments can result in large penalty fees, utility shutoffs, and evictions and can put low-income households at risk of losing adequate shelter.[3]

Material hardships and income-based poverty are related, but little is known about the prevalence of combinations of different hardships. In our study, we looked at combinations of utility and housing hardship, which are significant household expenses. We used nationally representative data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP*) to examine how household events commonly associated with poverty (such as income loss or the decline in health of a family member) may trigger missed utility and/or housing payments.

Utility Hardship Is More Common and Persistent than Housing Hardship

Figure 1 shows that from 2004 to 2014, around one in seven U.S. households was unable to meet utility and/or housing payments in the previous year. Between 2009 and 2011, the years following the 2008 financial crisis, 23 percent of U.S. households experienced utility or housing hardship at least once, and eight percent experienced at least one form of hardship in both years. When looking at the same households from one year to the next, utility hardship is both more common and persistent than housing hardship. Almost one-in-three of those who experienced only utility hardship in 2009-2010 still experienced utility hardship one year later, compared to about one-in-five that continued to experience housing hardship. This suggests that households may prioritize housing over utility payments due to the substantial threat of eviction.

Utility Hardship Is Linked to Greater Disadvantage than Housing Hardship

Households that miss utility and/or housing payments have lower incomes and higher poverty rates than households that do not. Compared with those without hardship, average household incomes are 32 percent lower for those that miss housing payments only, 45 percent lower for those that miss utility payments only, and 48 percent lower for those that miss both.

While households that experience both hardships have the lowest average incomes and highest poverty rates, those with utility hardship only are more disadvantaged than those with housing hardship only. They have higher poverty rates (31 percent versus 24 percent, respectively), lower average incomes ($2,977 per month versus $36,84), lower home ownership rates (46 percent versus 51 percent), and they more frequently have a household member in poor health (34 percent versus 29 percent).

Poor Health Predicts Utility and Housing Hardship

Our study examined the impact of changes in income, household composition, and a household member falling into poor health on utility and housing hardship. Among these types of household events, a household member falling into poor health was the strongest predictor of transitioning into both hardships. The probability of falling behind on utility and/or housing payments increased from about seven to eleven percent for households in which a member fell into poor health.

Like previous research,[4] our study found that adverse events (for example, income losses) more strongly predicted transitions into hardship than positive events (such as income gains) predicted transitions out of hardship. This suggests that many households experience challenges in recovering from income losses and other adverse events.

Utility Subsidies Are a Policy Option to Support the U.S. Households in Greatest Need

Policymakers interested in addressing material hardship among poor Americans often focus on programs for food, job training, or housing, but overlook options such as utility subsidies. The results of our study suggest that utility subsidies such as the federal Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) could help reduce multiple forms of hardship, given the more disadvantaged characteristics of households that experience utility hardship. Currently, only 19 percent of eligible households receive LIHEAP benefits, totaling 6 percent of all households.[5] Given reductions in the cash safety net and recent concerns about extreme poverty in the United States, policy solutions that address utility hardship may be an important tool to assist the families in greatest need.

* The SIPP interviewed the same households in both 2010 and 2011.

Ryan Finnigan is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at UC Davis.

Kelsey D. Meagher is a PhD Candidate in Sociology at UC Davis.

References

[1] Finnigan, Ryan, and Kelsey D. Meagher. Forthcoming. “Past Due: Combinations of Utility and Housing Hardship in the United States.” Sociological Perspectives.

[2] Desmond, Matthew. 2016. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. New York: Crown.

[3] Morduch, Jonathan, and Rachel Schneider. 2017. The Financial Diaries: How American Families Cope in a World of Uncertainty. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[4] Heflin, Colleen. 2016. “Family Instability and Material Hardship: Results from the 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 37(3):359-72.

[5] APPRISE (Applied Public Policy Research Institute for Study and Evaluation). 2014. LIHEAP Home Energy Notebook for Fiscal Year 2011. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.