Growth in Irregular Work Increased Poverty During and After Great Recession

By Ryan Finnigan and Joanna Hale, UC Davis

Jobs that offer hours that vary from week to week present significant challenges for low-wage workers. In a new study[1] we find that the number of workers with inconsistent work hours increased significantly throughout the Great Recession and recovery. These workers had lower incomes and higher poverty rates than those with steady hours. However, the increase in inconsistent hours was smaller among union members and in states with higher-than-average unionization. This suggests unionization could improve the chances a worker will have the steady income needed to plan for even short-term basic needs.

Unpredictable schedules and hours create significant challenges for hourly workers and their families. Fewer hours than expected makes long-term budgeting and meeting even basic expenses more difficult.[2] More hours than expected complicates planning for personal or family obligations.[3] Inconsistent hours may also have lasting consequences for low-wage service workers by hindering the pursuit of education or more stable jobs.[4]

Key Facts

- About 29% of workers from 2004-07 — before the Great Recession began — reported that their “hours vary” for at least a four-month period. This percentage increased to almost 40% among workers from 2008-13.

- Across both periods, workers who reported inconsistent work hours earned 15-20% less weekly than those reporting stable schedules. They were also 30-45% more likely to be in poverty.

- Before and after the Great Recession, workers who belonged to a labor union or lived in a state with higher-than-average rates of union membership were 2% less likely to have work schedules that changed from week to week.

High unemployment during the 2007-09 Great Recession undoubtedly contributed to the increase in irregular work hours, given the large growth of low-wage and part-time jobs in the recovery.[5] Other contributors include growth in temporary and contract work[6] and service employer practices like “just-in-time” scheduling to reduce costs.[7] Perhaps most profoundly, the general decline of institutions like labor unions also weakened workers’ general employment stability and earnings.[8]

Measuring Change in Inconsistent Hours

This study uses data from the 2004 and 2008 panels of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). Our first sample followed a group of hourly workers (N=31,237) between the ages of 25-55 from 2004-07. The second followed similar workers (N=31,924) from 2008-13. We estimate the percentage of workers who report “hours vary” instead of a consistent number of weekly hours over each four-month survey period.

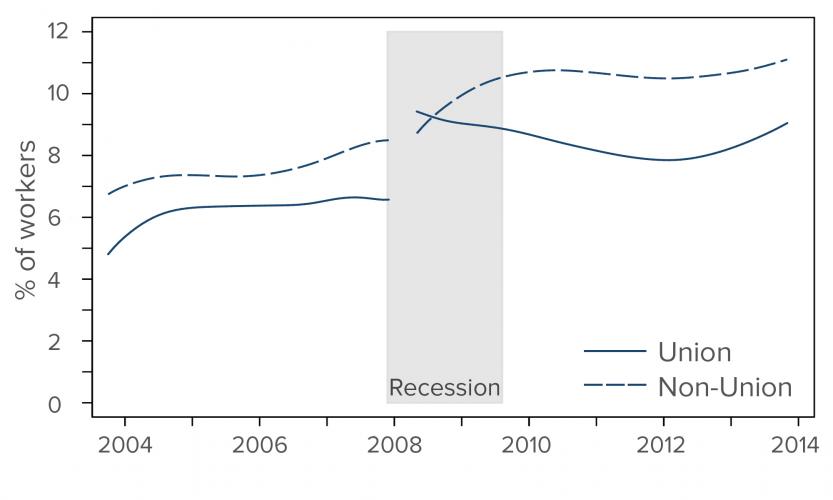

We then examine the impact unionization may have on workers reporting “hours vary” and the associated consequences for earnings. We measure union membership at the individual level based on data from the 2004 and 2008 SIPP panels, and at the state level with Current Population Survey (CPS) data.[9] Across both samples, the poverty rate for non-union workers was 7.1 percent. Among union members it was 2.2 percent.

A series of regression models estimate the relationship between unionization and the probability of reporting varying hours, as well as its associated earnings penalty. Our controls at the state level include gross state product per capita, economic growth, unemployment, effective minimum wage, population and region. Individual-level controls include age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, metropolitan status, industry and occupation.

Irregular Hours Increased after Great Recession

The Great Recession had a nearly immediate impact on the fraction of workers with irregular work hours. The percentage who reported “hours vary” over a four-month period increased by more than two percentage points in late 2008, an estimated total of more than two million workers. Between 2004 and the end of 2007, about 29 percent of all workers reported “hours vary” at any point for at least one four-month survey period. Between 2008 and mid-2012 this percentage was nearly 40 percent.

The proportion of workers who reported “hours vary” at any point during the calendar year increased as well. The total increased from about 15 percent in 2007 to 22 percent in 2009. The proportion remained above the pre-recession level even in 2013, at 17 percent.

Lower Income, Higher Poverty

Workers who reported “hours vary” were about three times more likely to work part-time because of slack work or an inability to find full-time work compared to workers with steady hours.

Workers with irregular hours also had higher rates of poverty.

Prior to the recession, poverty rates were 4.5 percentage points

higher for households with workers reporting inconsistent hours

(9.9%), compared to those with steadier hours (5.0%). After the

recession, the difference grew to 6.5 percentage points (poverty

rates of 13.6% and 7.1%, respectively).

Prior to the recession, workers with inconsistent hours earned

about 14 percent less overall than workers with stable hours.

During and after the recession, workers with inconsistent hours

earned about 18 percent less.

Unions Slowed Growth in Instability

Rates of unionization at the state level made a difference in how many workers reported inconsistent work hours. This holds true even when we controlled for workers’ individual characteristics and state economic factors. In states with low rates of unionization, below about ten percent, the probability of inconsistent hours was not significantly different between members and non-members. In states with high rates of unionization, about 26 percent, union members were 3.5 percentage points less likely than non-members to report inconsistent hours.

The earnings penalty associated with inconsistent hours is also smaller for union members. Union members who report inconsistent hours have wages that are 20 percent lower than those with steady hours, compared to a 29 percent penalty for non-members. The average union member who reports inconsistent hours still earns 9.4 percent more than a nonmember who works more regular hours.

Stabilizing Work and Income

This study shows that workers with hours that vary from week to week earn less and have higher rates of poverty. The continuing growth in these types of jobs means that many more low-wage workers could find it impossible to get ahead.

This study also suggests that unionization may increase the likelihood that workers have steady hours, higher pay and lower poverty rates. This is consistent with research showing the positive effects labor unions have on employment security and wages. Greater recognition of workers’ rights to organize and collectively bargain could help strengthen unions’ abilities to negotiate for workers’ security.

Strengthening the public safety net could also reduce economic hardships associated with insecure work hours. Housing and utility subsidies would help cover basic expenses during periods with low work availability, and child care subsidies would help families cope with unpredictable weekly hours.

Ryan Finnigan is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at UC Davis.

Joanna Hale is a Post-Doctoral Research Scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

[1] Finnigan, R. & J. Hale. 2016. “Work Variability and Unionization in the Great Recession.” UC Davis Center for Poverty Research Working Paper.

[2] Western, B., et al. 2012. “Economic Insecurity and Social Stratification.” Annual Review of Sociology.

[3] Lambert, S. 2008. “Passing the buck: Labor flexibility practices that transfer risk onto hourly workers.” Human Relations.

[4] Smith, V., et al. 2014. “Low-Wage Work Uncertainty often Traps Low-Wage Workers.” UC Davis Center for Poverty Research Policy Brief.

[5] Hout, M., et al. 2011. “Job Loss and Unemployment.” The Great Recession, ed. Grusky, D. et al. Russell Sage Foundation.

[6] Katz, L., et al. 2016. “The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States, 1995 -2015.” Working paper.

[7] Alexander, C., et al. 2015. “Underwork, Work-Hour Insecurity, and A New Approach to Wage and Hour Regulation.” Industrial Relations.

[8] Rosenfeld, J. 2014. What Unions No Longer Do. Harvard University Press.

[9] Hirsch, B. & Macpherson, D. 2003. “Union Membership and Coverage Database from the Current Population Survey: Note.” Industrial & Labor Relations Review.

#povertyresearch