WIC Participation Linked to Higher Diet Quality Among Young Children

Nancy Weinfield, Mid-Atlantic Permanente Research Inst; Christine Borger, Westat; Lauren Au, UC Davis; Shannon Whaley, Public Health Foundation Enterprises WIC; Danielle Berman, US Dept Ag Food & Nutrition; Lorrene Ritchie, UC Div of Ag & Nat Resources

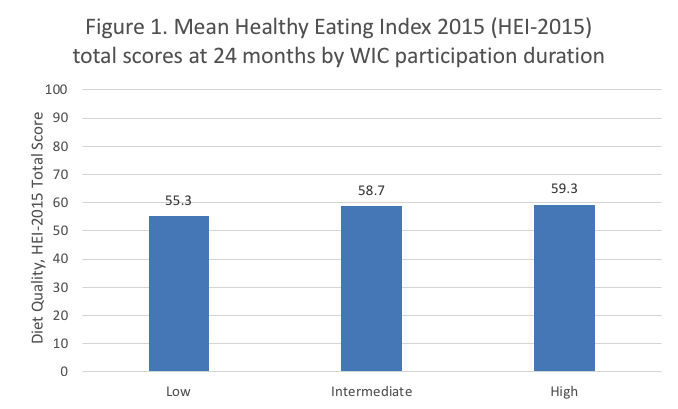

How does prolonged exposure to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) affect children’s diet quality? In a recent study, we examined the association between duration of WIC participation and diet quality of 24-month-old children. We found that WIC participation duration was significantly associated with diet quality. Children in the high-duration group had significantly higher Healthy Eating Index 2015 total scores (59.3) than children in the low-duration group (55.3). Children who received WIC benefits during most of the first two years of life had better diet quality at age 24 months than children who, despite remaining eligible for benefits, discontinued WIC benefits during infancy. These findings suggest nutritional benefits for eligible children who stay in the program longer, and highlight the importance of helping them to do so.

Key Facts

- WIC provides ongoing nutrition education for caregivers, and healthy foods for young children as they are developing food preferences and consumption patterns.

- In our study, children who received WIC benefits during most of the first two years of life had better diet quality at age 24 months than children who, despite remaining eligible for benefits, stopped receiving WIC benefits during infancy.

- Greater efforts are needed to improve the diets of children raised in low-income households, and to increase retention of children participating in WIC.

Higher parental education and income have long been associated with healthier diet among children.[1] The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), administered by the Food and Nutrition Service at the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), could reduce the effects of this income gap by providing nutrition education, breastfeeding support, health-care referrals, and supplemental foods to low-income pregnant and postpartum women, and to their children up to age five years. To qualify for the program, households must have an income at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty guideline or participate in Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. Program participants must also be at nutritional risk.

In studies that have compared WIC participants to higher income families that did not participate in WIC, children receiving WIC benefits had diets that were less healthy than those of their higher-income peers, particularly with regard to consumption of whole grains, whole fruit, and sugar-sweetened beverages.[2,3] However, when children participating in WIC were compared with nonparticipants from low-income households, children receiving WIC tended to have superior diets. Young children participating in WIC have been shown to consume less added sugar, more cow’s milk, more 100-percent juice, and more beans compared with income-eligible nonparticipants.[4,5]

Because WIC provides ongoing nutrition education for caregivers, and healthy foods for young children as they are developing food preferences and consumption patterns, longer exposure to WIC services may have a cumulative positive influence on child diet quality. In our study[6], we used the Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015)[7]—a diet quality tool showing adherence to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans—to evaluate diet quality in relation to duration of WIC participation.

Tracking Feeding Practices, Nutrition, and Health Outcomes

We used data from the WIC Infant and Toddler Feeding Practices Study 2 (WIC ITFPS-2), a national longitudinal study of feeding practices, nutrition, and health outcomes of children from birth to age nine years, who were initially enrolled in WIC.[8] In 2013, WIC ITFPS-2 sampled, screened, and enrolled participants in person from 80 WIC sites across 27 states and territories. Follow-up telephone interviews were conducted with study mothers from 2013 to 2016, prenatally and at child-ages 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, and 24 months, regardless of continuation of WIC program enrollment. Each interview included questions about the mother and target child’s receipt of WIC, sociodemographic characteristics, infant feeding practices and dietary intake, and other health-related behaviors. The full analysis sample for the study included 3,777 participants who completed a postnatal interview at 1 or 3 months. We utilized a subset of the sample comprising 1,349 participants that completed all postnatal interviews from 1 or 3 through 24 months.

The telephone interview at 24 months included a dietary recall through which foods, beverages, and dietary supplements consumed by the child were coded, and energy, nutrient, and food group intake were computed. At every interview, study participants were asked about their ongoing participation in WIC. Based on the responses, WIC duration was categorizedas low (infant year only), intermediate (some time beyond the infant year), or high (most of the first two years of life). When a participant indicated for the first time that neither she nor her child were receiving WIC benefits, she was asked a series of yes/no questions about the reasons they might have stopped going to WIC, including whether they stopped because she believed they no longer qualified for WIC benefits. The group that reported discontinuing WIC due to perceived program ineligibility was excluded from analyses, bringing the sample size to an unweighted sample of 1,250 participants.

Longer Duration Associated with Better Nutrition

The mean HEI-2015 total score for the study sample at 24-months old was 60.5 out of 100. Regarding WIC participation duration, among all study children, the groups were distributed as follows: 82 percent high duration, 15 percent intermediate, and 3 percent low. The HEI-2015 component scores that were significantly associated with WIC participation duration were total vegetables, greens and beans, seafood and plant protein, refined grains, and saturated fat. When participants who discontinued WIC due to perceived ineligibility were included in these analyses, mean values did not change substantially, and only saturated fat was no longer significantly associated with WIC duration.

Children in the high duration group (mean 59.3) had significantly higher HEI-2015 total scores than did children in the low duration group (mean 55.3), adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (Figure 1). Children whose mothers reported incomes at or below 130 percent of the poverty guideline had significantly higher HEI-2015 total scores (mean 58.4), compared with those with incomes above 130 percent of the poverty guideline (mean 57.2).

Nutrition Education and Participant Retention Both Crucial

We found that children who received WIC benefits during most of the first two years of life had better diet quality at age 24 months than children who, despite remaining eligible for benefits, stopped receiving WIC benefits during infancy. WIC may influence child diet quality through two mechanisms: the nutrition education provided to caregivers, and the nutritious foods provided for children. Foods purchased with WIC benefits are intended to be supplemental. Direct influences of the food package alone on diet quality may therefore be small in magnitude, while the nutrition education may be more influential.

Although children who remained on WIC for most or all of their first two years of life had better diet quality than children who discontinued WIC participation during infancy, adjusted mean total HEI-2015 scores were 59.3 and 55.3, respectively, and therefore still below the 80 to 100 total score that is considered indicative of a high-quality diet.Greater efforts are needed to improve the diets of children raised in low-income households. Overall, our study supports ongoing efforts by the WIC program to increase retention of children in the program.

Nancy S. Weinfield is a research scientist at Kaiser Permanente Mid-Atlantic Permanente Research Institute. Christine Borger is a senior study director at Westat. Lauren E. Au is an assistant professor of nutrition at the University of California, Davis. Lorrene D. Ritchie is director and cooperative extension specialist at the Nutrition Policy Institute, University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Shannon E. Whaley is director of research and evaluation, Public Health Foundation Enterprises WIC Program. Danielle Berman is a senior evidence analyst at the Office of Management and Budget.

References

[1] Patrick H, Nicklas TA. A review of family and social determinants of children’s eating patterns and diet quality. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24(2):83-92.

[2] Ponza M, Devaney B, Ziegler P, Reidy K, Squatrito C. Nutrient intakes and food choices of infants and toddlers participating in WIC. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(1 suppl 1):S71-S79.

[3] Jun S, Catellier DJ, Eldridge AL, Dwyer JT, Eicher-Miller HA, Bailey RL. Usual nutrient intakes from the diets of US children by WIC participation and income: Findings from the Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS) 2016. J Nutr. 2018;148(9 suppl):1567S-1574S.

[4] Siega-Riz AM, Kranz S, Blanchette D, Haines PS, Guilkey DK, Popkin BM. The effect of participation in the WIC program on preschoolers’ diets. J Pediatr. 2004;144(2):229-234.

[5] Cole N, Fox MK. Diet Quality of American Young Children by WIC Participation Status: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Research, Nutrition and Analysis; 2008.

[6] Weinfield, N.S., Borger, C., Au, L.E., Whaley, S.E., Berman, D., Ritchie, L.D. 2020. Longer Participation in WIC Is Associated with Better Diet Quality in 24-Month-Old Children. J Acad Nutr Diet, 120 (6) 963-971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2019.12.012

[7] National Cancer Institute. Healthy Eating Index overview and background. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/. Updated August 13, 2018. Accessed December 6, 2018.

[8] Borger C, Weinfield NS, Zimmerman T, et al. WIC Infant and Toddler Feeding Practices Study 2: Second year report. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service; 2018.