Socioeconomic Features Among Strongest Predictors of Neighborhood-Level Violence

By Veronica A. Pear, Colette Smirniotis and Rose M. C. Kagawa, UC Davis

Violence is a leading cause of death and disparity in the United States. Physical and social environments such as neighborhoods can contribute to the prevention or fostering of violence.

In a recent study, we used machine learning to identify features of the local environment that are most predictive of violence in two cities struggling with disinvestment and crime.

We found that socioeconomic features, along with building quality and type, had the highest importance in predicting violent crime, including firearm-involved violent crime. Density of multifamily homes and road networks also proved important, as did percentage of population that was white.

Our findings suggest that policymakers interested in reducing violent crime should consider boosting socioeconomic support for neighborhoods in which it is most prevalent.

Key Facts

- Violence is a leading cause of death and disparity in the United States.

- Socioeconomic features, along with building quality and type, had the highest importance in predicting violent neighborhood crime.

- Policymakers interested in reducing violent crime should explore neighborhood-level interventions, especially in disadvantaged areas.

Background

In 2020, firearm violence surpassed motor vehicle crash deaths as the leading cause of death for adolescents in the United States.[1] In 2022, there were 48,204 firearm-involved deaths, 19,651 of which were homicides, and an estimated 640,710 firearm victimizations in total.[2,3] Previous research has related features of the physical environment to crime risk. For violent crimes, common “attractors” include schools, and particularly public secondary schools, parks, bars and restaurants where alcohol is served and public transportation sites such as bus stops.[4] Housing age and location are also potential drivers of violence. Other landscape factors such as neighborhood greenspace, and transportation design are also associated with firearm violence and related factors such as aggression and crime.[5]

Social and economic environments also play a critical role in neighborhood safety. Economic inequality and limited education and economic opportunities, concentrated disadvantage and poverty, and low levels of collective efficacy are all associated with community violence.[6] For example, a recent study in Seattle, Washington found a strong association between neighborhood disadvantage and the count of firearm injuries at the census tract level.[7]

In our study[8], we examined the importance of various contextual features in predicting violent crime over a nine-year period in Cleveland, Ohio and Detroit, Michigan—two post-industrial cities in which levels of firearm violence far exceed the national average.

Exploring predictors of neighborhood-level violence

We paired data on 55 census-tract features in Cleveland and Detroit with machine-learning techniques to identify those features most predictive of violent crime. The 55 features covered building quality and type, public goods and services, residential stability, socioeconomic features, historical features, and demographic features.

Socioeconomic features included census-tract measures of employment, income, education, female-headed households, individuals serving in the armed forces, residential economic segregation, households with crowding, population using public transportation, median residential sales price, and parcels that are tax delinquent or foreclosed.

Demographic features included census-tract population count, percentage of population that were young men aged 15 to 29, racial and ethnic distributions, racial residential segregation, and naturalized and non-citizen immigrants. Because crime data with sufficiently accurate location indicators were not available for Detroit, our analysis focused primarily, though not exclusively, on Cleveland.

Socioeconomic features among strongest predictors of crime

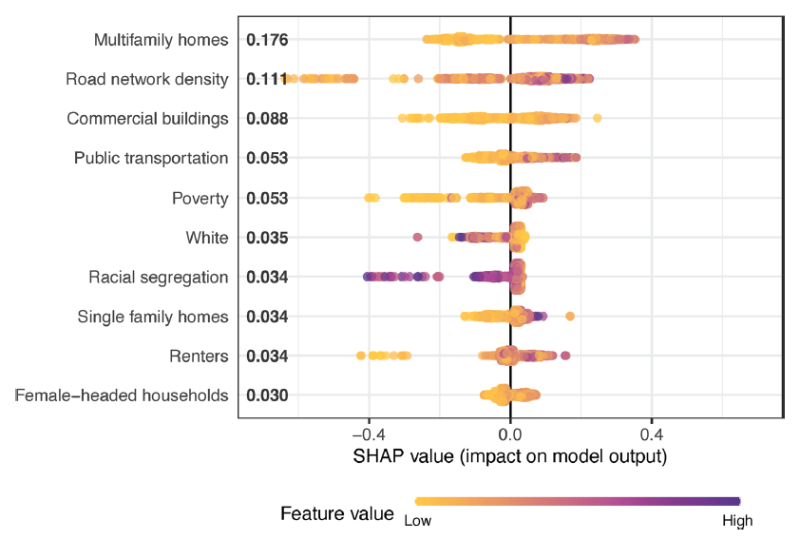

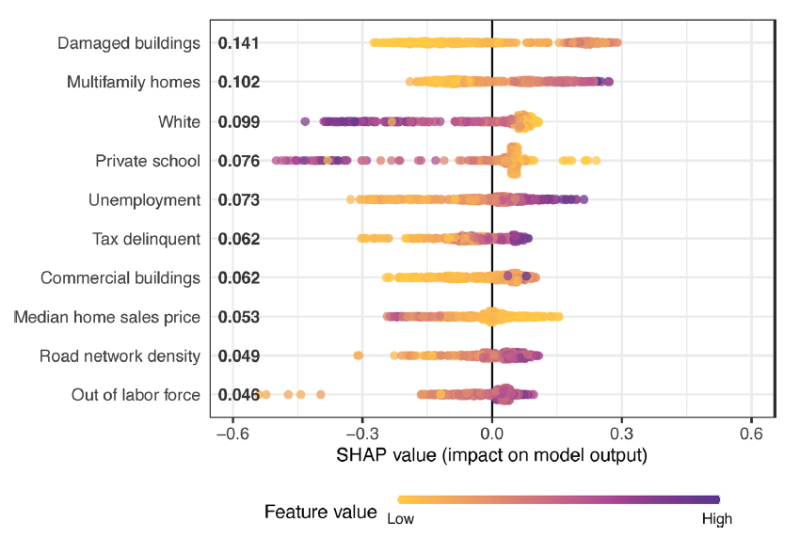

We found that the most important variables for violent crime in Cleveland were in the domains of building quality and type or socioeconomic features. Both outcomes had several variables in common: multifamily homes per square mile, road network density, commercial buildings per square mile, and percentage white alone. Higher values of multifamily homes, road network density, and commercial buildings were associated with higher values of the outcomes, where the inverse relationship held for percentage white.

Figure 1. Top 10 Predictors of Pt.1 Violence in Cleveland. Shapley Value by Feature Value

For violence (Figure 1), the most important variables included population using public transportation, population below 150 percent of the poverty line, racial residential segregation, single family homes per square mile, percentage of occupied housing units that are renter occupied, and percentage of female-headed households. For firearm violence (Figure 2), the remaining variables included damaged buildings per square mile, percentage of children enrolled in private school, percentage unemployed, percentage of parcels that are tax delinquent, median home sales price, and percentage out of the labor force.

Figure 2. Top 10 Predictors of Pt.1 Firearm Violence in Cleveland. Shapley Value by Feature Value

For homicide and firearm homicide in both Cleveland and Detroit, the percentages of female-headed households and Black residents proved most important. Single family homes, large apartment buildings, and damaged buildings per square mile also had high importance. Unemployment proved important in Cleveland. In Detroit, residential racial segregation, small apartment buildings per square mile, and road network density appeared as highly important variables.

Neighborhood-level policy interventions likely to help reduce violent crime

Our findings suggest that socioeconomic status plays an important role in crime prediction. The pathways linking poverty and its associated contexts to crime are numerous and complex. Unemployment may push people to engage in the illicit labor market where criminal activities may constitute or supplement income that is otherwise hard to come by.[9] Lower levels of employment, and perhaps particularly, higher rates of having left the labor force completely, serve as direct motivators for criminal engagement, indicators of weak social ties, and signs of reduced economic opportunity. Elevated rates of family disruption, as proxied by female-headed households, could be related to joblessness, incarceration, or other factors, and higher proportions of renters are signs of a more transient population that may have weaker informal social controls.[10]

Land-use characteristics also turned out to be significant—at times even more influential than socioeconomic factors. Census tract indicators reflecting mixed-use neighborhoods with higher concentrations of multi-family housing, renters, roadways, commercial structures, and greater reliance on public transit were among the strongest predictors of increased violent crime rates.

Traditional markers of socioeconomic disadvantage—such as poverty levels and the share of female-headed households—emerged as major predictors of general violent crime but not of violent firearm-related crime. The variables most strongly associated with firearm violence (but not overall violence) pointed to more severe forms of neighborhood hardship. These included unemployment, tax delinquency, property sales values, and housing quality. Such conditions reflect a deeply unstable housing market, where property values fall below mortgage balances. Combined with widespread unemployment and a concentration of deteriorating homes, these factors signal communities facing significant structural obstacles to financial stability.

Our study suggests that the local environment plays an important role in violence. Policymakers interested in reducing violent crime should explore neighborhood-level interventions, especially in disadvantaged areas.

Veronica A. Pear is an assistant professor in residence in the School of Medicine at UC Davis.

Colette Smirniotis is a research data analyst in the Centers for Violence Prevention at UC Davis.

Rose M. C. Kagawa is an associate professor in residence in the School of Medicine at UC Davis.

References

1. Goldstick JE, Cunningham RM, Carter PM. Current causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(20):1955–6.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. [cited 2024 July 31]. WISQARS Fatal and Nonfatal Injury Reports. Available from: https://wisqars.cdc.gov/reports/

3. Thompson A, Tapp SN, Criminal Victimization. 2022 [Internet]. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2023 [cited 2024 July 31]. Report No.: NCJ 307089. Available from: https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/cv22.pdf

4. Drawve G, Barnum JD. Place-based risk factors for aggravated assault across police divisions in Little Rock, Arkansas. J Crime Justice. 2018;41(2):173–92.

5. Younan D, Tuvblad C, Li L, Wu J, Lurmann F, Franklin M et al. Environmental Determinants of Aggression in Adolescents: Role of Urban Neighborhood Greenspace. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 July 1;55(7):591–601.

6. Kegler SR, Dahlberg LL, Vivolo-Kantor AM. A descriptive exploration of the geographic and sociodemographic concentration of firearm homicide in the United States, 2004–2018. Prev Med. 2021;153:106767.

7. Dalve K, Gause E, Mills B, Floyd AS, Rivara FP, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Neighborhood disadvantage and firearm injury: does shooting location matter? Inj Epidemiol. 2021;8(1):10.

8. Pear VA, Smirniotis C. & Kagawa RMC. Predicting neighborhood-level violence from features of the physical and social environment with machine learning. Inj. Epidemiol. 2025, 1,75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-025-00629-2

9. Fagan J, Freeman RB. Crime and work. Crime and Justice. 1999; 25:225–90.

10. Sampson RJ. Urban black violence: the effect of male joblessness and family disruption. Am J Sociol. 1987;93(2):348–82.