Safety-Net Programs Underused by Eligible Hispanic Families

By Marianne Bitler, UC Davis, and Lisa A. Gennetian, Christina Gibson-Davis, and Marcos A. Rangel, Duke University

Historically, Hispanic families have used means-tested assistance less than high-poverty peers, with anti-immigrant politics and policies potentially acting as a barrier. In a recent study, we documented the participation of Hispanic children in three anti-poverty programs: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). We compared across age and parental citizenship, and also explored the correlation of participation with state immigrant-based restrictions.

We found that Hispanic-citizen children with citizen parents participated in SNAP and Medicaid more than Hispanic-citizen children with noncitizen parents. Also, foreign-born Hispanic mothers used Medicaid less than their socioeconomic status would suggest. However, we found no evidence that child participation in WIC varied by mother’s nativity. State policies that restrict immigrant program use correlate to lower SNAP and Medicaid uptake among citizen children of foreign-born Hispanic mothers. WIC participation may be greater because it is delivered through nonprofit clinics, and WIC eligibility for immigrants is largely unrestricted.

Key Facts

- Roughly one in three children who live in poverty in the United States is Hispanic, with one in ten residing in deep poverty.

- Citizen Hispanic children with parents born outside the U.S. participated in SNAP and Medicaid at lower levels than might have been predicted by their socioeconomic status.

- Differential participation based on parental citizenship status raises important questions about whether citizen children in the U.S., who otherwise may qualify for benefits, are not fully participating in programs because of the chilling effects of state-level policies.

Social safety net programs provide support to poor children, reducing the negative impact of income deprivation on children’s future well-being.[1] SNAP (formerly known as food stamps) provides income earmarked for food via electronic benefit cards for use at food stores. Medicaid covers health-care costs for eligible low-income families. WIC provides the ability (now through EBT cards, previously with vouchers) to purchase foods high in nutrients important for young children and pregnant women.

Roughly one in three children who live in poverty in the United States is Hispanic, with one in ten residing in deep poverty.[2] However, Hispanic families make less use of means-tested social safety net programs than high-poverty peers. Why? Some research suggests that federal and state legislators, along with administrators, create administrative burdens in the form of punitive rules and complex processes to access and maintain benefits.[3] There is also evidence that, because many low-income Hispanic children reside in racially diverse states, Hispanic families may be affected by strategies intended to exclude African Americans.[4] This effect of decentralized authority over the implementation of social benefits may have spilled over to Hispanic families under the agenda of immigrant exclusion.[5]

Hispanic families’ decisions to apply for public benefits may be particularly susceptible to eligibility determination based on household members’ and parents’ immigration statuses, as well as to the broader landscape of state and federal immigration policy and public-charge concerns. In our study, we exploited the variation in use of SNAP, Medicaid, and WIC among Hispanic families by nativity and immigration status to assess how state-level policies toward benefit use among immigrants correlates with uptake of these programs among Hispanic families.[6]

Examining Benefit Use Among Hispanic Families

We began by looking at pre-COVID use of SNAP, Medicaid, and WIC among all children, separating Hispanic children and children of other race/ethnic groups. To do so, we used Current Population Survey (CPS) from 2019 for Medicaid and SNAP, and from 2016 to 2018 for WIC. We focused on children in the CPS who were born in the U.S. We then split the sample by whether a parent was born outside the U.S. or whether the child’s mother reported being a citizen.

To further examine participation in WIC and Medicaid among infants, we relied on U.S. birth-certificate data from the CDC’s Natalit Files, which cover 99 percent of U.S. births. We used these data to present patterns of WIC and Medicaid use, presenting contrasts among five subgroups: foreign-born Hispanic, U.S.-born Hispanic, U.S.-born white, U.S.-born Black, and foreign-born non-Hispanic. Program use was further considered by level of education (where available) and state of residence.

Policy restrictions for immigrants were drawn from the State Immigration Policy Resource. We concentrated on policies about public benefits, and grouped states into three categories: low, medium, and high restrictions on use of policies by immigrants. We compared participation rates among Hispanic children for these three groups of states, contrasting participation for those with parents born in the United States or mothers born in the United States with others.

For Hispanic Children, Program Use Varied by Nativity and Citizenship Status

We found similar levels of SNAP use across age and by parents’ nativity. Medicaid use was higher for children with at least one parent born outside the U.S., likely partially due to different income levels across these groups. Black and Hispanic children had comparable Medicaid, SNAP, and WIC usage rates, with both demographic subgroups using the programs at higher rates than non-Hispanic white children. Usage among Hispanic children varied by nativity and citizenship status, however, with children of noncitizen mothers using the programs at higher rates than Hispanic children whose mothers were born in the United States or became a naturalized citizen. Hispanic children of noncitizen mothers had the highest rates of Medicaid usage (63 percent for ages 0–5, 61 percent for ages 6–17) and WIC usage (35 percent) of any subgroup. For both Medicaid and SNAP, Hispanic children of citizen mothers were about as likely to participate in these programs as Black non-Hispanic children, whereas Hispanic children of noncitizen mothers are less likely to do so (Figure 1). By contrast, WIC participation was higher among Hispanic children of noncitizen mothers than of citizen mothers.

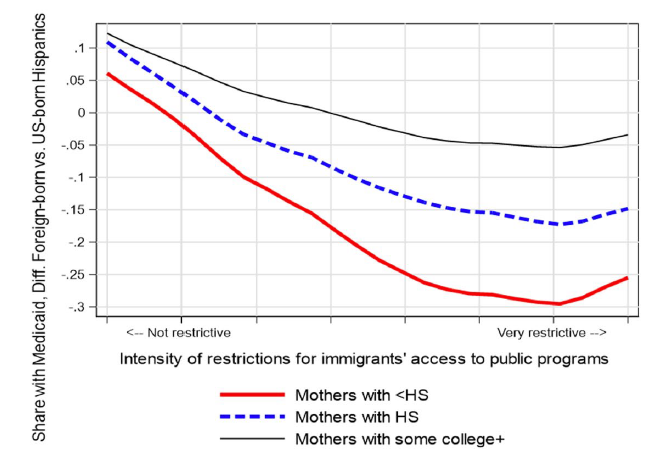

Figure 1: Difference in Medicaid Participation between Foreign- and U.S.-Born Hispanic Mothers by State-Level Restrictiveness of Access to Public Programs (2011–2018), by Maternal Education Level

State-level policy restrictions informed SNAP and Medicaid, but not WIC, use. Participation levels tended to be higher in the states having less restrictive policies toward immigrants, with larger differences among children with a parent born outside the U.S. Additionally, participation levels were consistently higher for Hispanic children with two U.S.-born parents. For WIC, by contrast, participation did not substantially vary by state restrictiveness. WIC use was higher for children with a foreign-born parent residing in states with low or medium restriction levels, and only slightly higher among this group in the high-restriction states.

Medicaid served as the primary health care coverage for more than half of all births to Hispanic mothers, with the program paying for a slightly higher fraction of births to foreign-born Hispanic mothers (58.6 percent) than to U.S.-born Hispanic mothers (56.4 percent). The majority of Hispanic mothers also reported receiving WIC during pregnancy, with foreign-born Hispanic mothers using the program more than U.S.-born Hispanic mothers. Use of Medicaid and WIC among Hispanic mothers was comparable to that of U.S.-born Black mothers, and higher than Medicaid or WIC use for U.S.-born white mothers or non-Hispanic foreign-born mothers.

WIC participation did not vary by nativity across states. State restrictiveness had little association with WIC use, as expected, given that most states do not impose restrictions on WIC. However, for Medicaid, increased restrictiveness had a substantial impact on the participation gap between foreign-born Hispanic mothers and their U.S.-born counterparts of equivalent educational attainment.

Efficacy of the Safety Net May Be Affected by Restrictions on Participation by Immigrants

Relative to citizen Hispanic children with U.S.-born parents and to non-Hispanic children, citizen Hispanic children with parents or mothers born outside the U.S. were less likely to participate in Medicaid or SNAP. Indeed, they participated at lower levels than might have been predicted by their socioeconomic status. Yet as U.S. citizens, these children were fully eligible for these programs. Our results likely reflect the chilling effect of anti-immigrant policy on benefit use. They suggest that recent U.S. restrictions aimed at immigrants, along with heated debate around such policies, have discouraged benefit use among citizen children as well.

In short, many U.S.-born, citizen Hispanic children are seemingly not accessing Medicaid when they are likely eligible. Their differential participation based on the immigrant status of their parents raises important equity concerns as to how America treats its youth, and how to cultivate access to all children who are born in the U.S. State-level choices regarding benefit eligibility reflect the deep partisan divide on immigrants and immigration and whether access to benefits should be defined relative to country of birth, citizenship status, or both. As long as the U.S. safety net continues to reflect divisions about immigration, many Hispanic children—regardless of country of birth—may miss out on the anti-poverty benefits that these programs are intended to deliver.

This work focuses primarily on participation among immigrants, but it ties in with an increasingly large literature on ‘administrative burden’, which highlights how interactions with bureaucrats, complicated applications, and complex rules can discourage people from applying for government benefits despite being eligible to do so. In the context of WIC, recent work has shown that the program also imposes some burdens on benefit use by complicating recipients’ interactions with stores.[7,8] SNAP and Medicaid are also documented to impose such burdens on use for families with children.[9] Our work points to the importance of continuing to interrogate administrative burdens that fall on citizen children and families, and of building best practices from examples (such as WIC) in which burdens appear lower.

Marianne Bitler is a professor of economics at UC Davis.

Lisa A. Gennetian is a professor of public policy at Duke University.

Christina Gibson-Davis is a professor of public policy and sociology at Duke University.

Marcos A. Rangel is a professor of public policy and economics at Duke University.

References

[1] Hoynes H, Whitmore Schanzenbach D, Almond D. 2016. Long-run impacts of childhood access to the safety net. American Economic Review 106 (4): 903–34.

[2] Guzman L, Thomson D, Ryberg R. 2021. Understanding the Influence of Latino Diversity over Child Poverty in the United States. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 696(1): 246-271.

[3] Herd P, Moynihan D. 2019. Administrative burden: Policymaking by other means. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

[4] Lichter DT, Johnson KM. 2021. Opportunity and Place: Latino Children and America’s Future. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 696(1): 20-45.

[5] Barnes CY, and Gennetian LA. 2021. Experiences of Hispanic Families and Social Services in the Racially Segregated Southeast: Views from Administrators and Workers in North Carolina. Race and Social Problems 13:6–21.

[6] Bitler, M, Gennetian LA, Gibson-Davis C, Rangel MA. 2021. Means-Tested Safety Net Programs and Hispanic Families: Evidence from Medicaid, SNAP, and WIC. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 696(1): 274-305. doi:10.1177/00027162211046591

[7] Barnes, C. 2021. “It Takes a While to Get Used to:” The Costs of Redeeming Public Benefits. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 31(2): 295-310.

[8] Chauvenet, C, De Marco, M, Barnes, C, Ammerman, AS. 2019. “WIC Recipients in the Retail Environment: A Qualitative Study Assessing Customer Experience and Satisfaction.” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 119(3): 416-424.

[9] Heinrich, C, Camacho, S, Henderson, SC, Hernandex, M, and Joshi, E. 2022. “Consequences of Administrative Burden for Social Safety Nets that Support the Health Development of Children. Journal of Policy and Management 41(1): 11-44.