Safety Net Enables Faster, More Permanent Exit from Deep Poverty

By Ann Huff Stevens, UC Davis

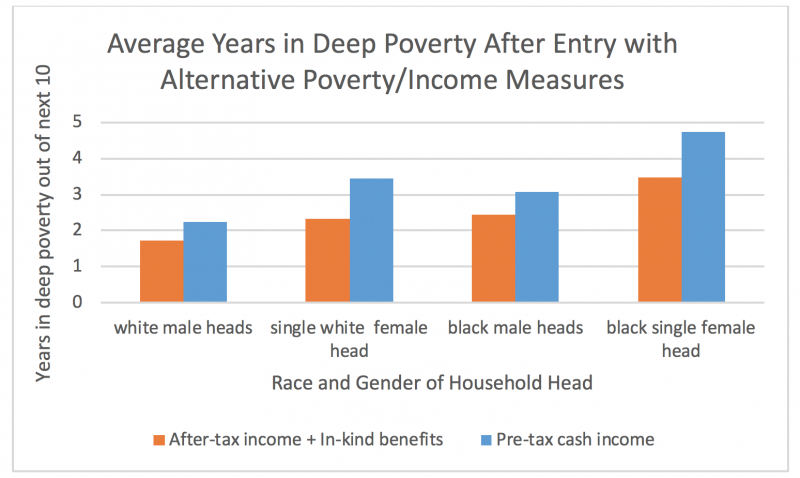

Living in “deep poverty” means living on an income less than half the official poverty threshold, or, for a family of three in 2017, living with annual income of less than $9758. According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census, 18.5 million individuals in the United States—5.7 percent of the population—lived in deep poverty in 2017. At such low levels of income, it may be particularly important to understand for how long individuals continue to live in deep poverty. My recent study investigates the long-term persistence of deep poverty. While most spells of deep poverty in the U.S. are short, with two-thirds of individuals who fall into deep poverty exiting in two years or less, re-entry is also common. Indeed, depending on race and family structure, individuals beginning a stay in deep poverty will on average spend between 2.2 and 4.7 years in deep poverty over the next decade. Adding common in-kind and tax-related benefits to the definition of income reduces the average time in deep poverty to 1.7 to 3.5 years out of the next ten.

Key Facts

- In 2017, 18.5 million individuals in the United States—5.7 percent of the population—lived in deep poverty.

- Half of the individuals exiting deep poverty within the first year will return to deep poverty within the next five years.

- High rates of return to deep poverty mean that individuals beginning a stay in deep poverty will on average spend between 2.2 and 4.7 years in deep poverty over the next decade.

Estimating Rates of Transition

To answer questions about the persistence of deep poverty, I used data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), focusing on the survey years 1985 through 2015. The PSID collects detailed information on family income and its components, and on family composition and changes in family composition over time. It offers uniquely valuable data for anyone studying the persistence of deep poverty over the long term.

Given the potential reliance of individuals living in deep poverty on non-cash benefits, such as food stamps and housing subsidies, and the growing role of tax credits for low-income individuals, I also estimated persistence in deep poverty using a modified income definition that adds the value of food stamps, housing subsidies and refundable tax credits to cash income. I then estimated transition rates out of and back into deep poverty to summarize the length of both completed single spells of deep poverty and to simulate total time spent in deep poverty across multiple spells.

Exits from Deep Poverty Occur Quickly, But Are Rarely Permanent

Among those beginning a stay in deep poverty in the U.S., 59 percent escape deep poverty after only a single year. Using an expanded definition of deep poverty that counts in-kind assistance and tax credits as income (but maintains the official poverty thresholds), I found that 68 percent of those falling into deep poverty escape after just one year.

However, as with poverty, exits from deep poverty are unlikely to be permanent. Nearly one-quarter of individuals escaping deep poverty return to deep poverty after just one year out, and approximately one-third have returned to deep poverty after two years out. More than half of those formerly experiencing spells of deep poverty have returned within five years.

By combining estimated probabilities of ending a spell of deep poverty—consecutive years spent below half the official poverty line—with probabilities of returning to deep poverty, I was able to estimate the total fraction of time spent in deep poverty across multiple spells.

Additionally, in the years after an escape from deep poverty, many individuals remain between half the poverty line and the poverty line, suggesting that the degree of income mobility is modest. Four years after rising above half the poverty line, or escaping deep poverty, nearly one-quarter of individuals are still below the poverty line.

Variation by Race and Gender of the Head of Household

The persistence of deep poverty varies considerably between different categories of household. Specifically, children, those in single female-headed households, and Blacks have lower exit rates out of deep poverty. For the purposes of these statistics, and following the categorization used by the PSID data, for married couples the male is assigned as the head of household. Female headed households are equivalent (in these data) to single female headed households.

The figure below illustrates differences in the persistence of deep poverty by the race and sex of the head of household. The blue bars show persistence of deep poverty using half the official poverty line to define deep poverty. The figure shows, for individuals with household heads of the given race and sex in their initial year of deep poverty, the average number of years over the next decade they will be in deep poverty. Individuals in households headed by white men who begin a stay in deep poverty can expect to spend just over two of the next ten years in deep poverty. For those living in households headed by single white women, however, deep poverty is more persistent, with an average stay of nearly three and half years.

Black individuals who fall into deep poverty face substantially longer stays in deep poverty. Those in households headed by black males face an average time in deep poverty of over three years. Those in households headed by single black women will spend almost half of the next decade in deep poverty.

Powerful Role of the Safety Net

The figure also shows an analysis of persistence if we add major in-kind benefits and refundable tax credits to our definition of income for determining deep poverty. When these additional resources are counted as household incomes, time spent in deep poverty falls. Total years in deep poverty for those beginning a spell in deep poverty under this definition range from 1.7 to 3.5 years out of the next ten.

While these calculations do not speak to potential behavioral responses of the safety net—the idea that the presence of safety-net programs may alter an individual’s behavior and income in a variety of ways—they do show an important role for the safety net in protecting against long-term deep poverty.

Regardless of the income definition used, deep poverty is commonly a persistent state. Most of those escaping a stay in deep poverty will return within the next few years. By understanding and quantifying the extent to which it persists, we can better identify characteristics that might predict chronic deep poverty in the U.S. While deep poverty is a relatively rare occurrence, it is far more likely among children, single-parent families, and racial minorities. Indeed, the duration and frequency of these spells varies by demographic. Fully half of those in long-term deep poverty are children and more than two-thirds are single-female headed households. The likelihood that such chronically low income has lasting effects on children suggests that effective efforts to address chronic deep poverty would be particularly beneficial.

Ann Huff Stevens is a Professor of Economics at UC Davis and the Deputy Director of the UC Davis Center for Poverty Research.