Resilience Factors Improve Health Prospects for Disadvantaged Children

By Camelia Hostinar, UC Davis, and Gregory E. Miller, Northwestern University

Economic hardship during childhood contributes to worse mental and physical health across the lifespan. Over the past decade, researchers have begun to highlight the behavioral and biological pathways that underlie these disparities, and to identify protective factors—supportive relationships, for example—that mitigate against their occurrence. In this brief, we summarize some of this recent research and the new challenges it presents. We also make suggestions to inform both policy and practice for youth experiencing economic hardship. In particular, we recommend early intervention on multiple fronts to improve the physical and psychological resilience of children growing up in trying economic circumstances.

Key Facts

Economic hardship during childhood contributes to worse mental and physical health across the lifespan.

Resilience factors such as supportive relationships are associated with better health prospects for children facing economic hardship.

Policymakers should propose new programs, or increase investment into existing programs, to foster resilience among disadvantaged children.

Roughly 21 percent of American children live below the federal poverty level. An even larger share (43 percent) grow up in low-income families that earn less than twice the poverty level.[1] That number rises even higher for members of racial and ethnic minority groups. The consequences of these statistics are profound. In addition to worse outcomes in education, mental health, and criminal justice system involvement, childhood hardship can lead to physical health problems, and to higher rates of morbidity and mortality from multiple conditions across the lifespan.

These health disparities begin at birth, with marked socioeconomic-status (SES) differences in preterm delivery, growth restriction, and infant mortality. They continue through childhood, where they manifest in common pediatric conditions like obesity, injury, and asthma.[2] They also persist into adulthood, during which childhood SES forecasts higher rates of coronary heart disease, stroke, and premature mortality, independent of adult SES.[3] Researchers believe that SES “gets under the skin” to affect health in both the short and long term. In other words, stress is likely a key factor here, as are the stress-mediating systems it activates.

Some children, though, are more resilient than others. For these children, low SES does not, in and of itself, necessarily lead directly to poor health outcomes.[4] This was illustrated in a study in which adults were exposed to a rhinovirus and then monitored in quarantine for emergence of the common cold.[5] Participants who had experienced low childhood SES were more likely to become infected with the virus and show cold symptoms compared to those who grew up in high-SES homes. However, despite this greater risk, 50 percent of those growing up in low-SES conditions did not get sick. These findings raise questions about the factors that may protect the health of children confronting economic hardship.

Protective Factors for Children in Poverty

Fortunately, it is possible to lessen the extent of SES-based health disparities through the nurture of certain protective factors that promote psychological and/or physical resilience. Proof of the value of these factors lies in the fact that some poor children remain in good health despite the odds.

Psychological resilience has been defined as positive adaptation despite adversity. More than simply a trait of a given individual, it is thought to be a dynamic process that reflects multiple transactions between environmental conditions and individual characteristics, leading to successful outcomes.[6] Environmental conditions contributing to such psychological resilience include: positive close relationships with caregivers; emotionally supportive peers, teachers, role models, and romantic partners; cohesive neighborhood communities and organizations such as churches and youth clubs; and high-quality schools.

At the individual level, psychological resilience may arise from a combination of factors, including: active temperament; sociable temperament; curiosity and intelligence; self-esteem; effective interpersonal and communication skills; achievement-motivation related to school or other special talents; a belief system or a sense of meaning in life; strong self-control; and coping skills.[7]

In terms of resilience to physical health problems, supportive relationships in early life (especially parental warmth) are crucial. Early-life maternal warmth operates as a buffer, weakening the usual association between economic hardship and negative health outcomes such as inflammation and metabolic syndrome. Children experiencing insensitive or abusive care are more likely to display hypervigilance to threat, a state that is known to contribute to cardiovascular and metabolic disease.[8] To add further complexity, parents’ ability to provide beneficial warmth and support may be hindered when their own basic needs for food and a safe home are not met due to low SES.

Promoting Resilience to Adversity

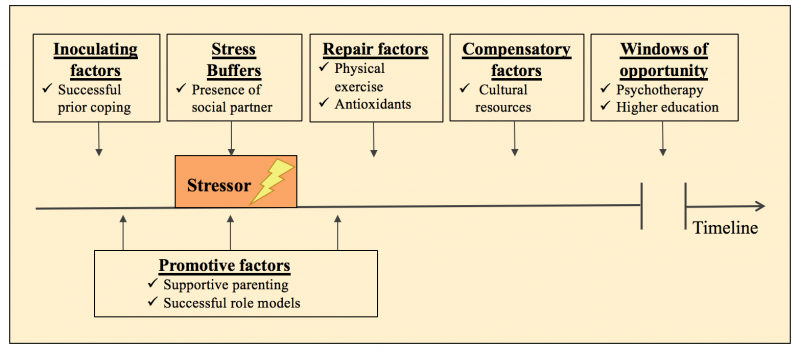

A significant challenge facing researchers and policymakers attempting to address psychological and physical resilience simultaneously is a lack of a common language. In the figure below, we propose several terms to alleviate this problem, and in doing so define a set of protective factors promoting resilience to adversity. As the figure shows, we need to embrace a more holistic, interactive, and dynamic view of the adaptation processes that enable at-risk children to become resilient in various domains.

Inoculating factors occur before the onset of a stressor and “steel” or “immunize” us by dampening stress responses to future adversity. Stress buffers are factors that dampen stress responses and the negative impact of adverse circumstances while they are occurring. Repair factors can be defined as factors that restore aspects of biological or psychological functioning and promote faster recovery after stressful events. Compensatory factors can begin to act after the repair stage is completed and can counterbalance deficits that linger in the aftermath of adversity. Windows of opportunity refer to major life changes that afford chances for improved outcomes, often long after the experience of adversity. Promotive factors provide continuous benefits for child development under both low-stress and high-stress conditions.

Intervene Early for Greatest Returns

The medical, psychological, academic and economic problems of disadvantaged children require solutions that address multiple needs simultaneously, in a holistic and context-informed manner. In other words, we must intervene early on multiple fronts. Specifically, we need renewed commitment to multipronged social programs that can create enough positive synergies within economically marginalized communities, helping children and families to adapt and grow more resilient. Because skills beget skills, intervention in the first few years of life yields the greatest returns.

Experimental programs like the Perry Preschool and Abecedarian projects not only have long-lasting benefits into adulthood, but also provide adequate returns on investment. Despite this evidence, national programs such as Head Start have been stripped of many of their social-services, medical-care, and health-education components, weakening their beneficial impacts for children. In order to nurture the protective factors described above and bolster resilience among disadvantaged children, policymakers should propose new programs, or increase investment into existing multipronged programs, for families facing economic hardship.

Camelia Hostinar is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Davis.

Gregory E. Miller is a Professor of Psychology at Northwestern University.

This policy brief was supported by funding from the UC Office of the President Multicampus Research Programs and Initiatives, Grant MRI-19-601054.

References

[1] Jiang, Y., Granja, M.R., and Koball, H. (2017). Basic Facts about Low-Income Children: Children under 18 Years, 2015. National Center for Children in Poverty. http://www.nccp.org/publications/pub_1170.html.

[2] Braveman, P. A., Cubbin, C., Egerter, S., Williams, D. R., & Pamuk, E. (2010). Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. American Journal of Public Health, 100 Suppl, S186–96. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082

[3] Galobardes, B., Smith, G. D., & Lynch, J. W. (2006). Systematic review of the influence of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on risk for cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Annals of Epidemiology, 16(2), 91–104. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.053

[4] Chen, E., & Miller, G. E. (2013). Socioeconomic status and health: Mediating and moderating factors. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 723–49.

[5] Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., Turner, R. B., Alper, C. M., & Skoner, D. P. (2004). Childhood socioeconomic status and host resistance to infectious illness in adulthood. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66, 553–558. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000126200.05189.d3

[6] Cicchetti, D. (2013). Annual Research Review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children-past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 402–422. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x

[7] Masten, A. S., & Narayan, A. J. (2012). Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: Pathways of risk and resilience. Annual Reviews Psychology, 63, 227–257.

[8] Miller, G. E., Chen, E., & Parker, K. J. (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 137(6), 959–97.