Release From Detention Reduces Stress and Improves Health Among Detained Immigrants

By Caitlin Patler, UC Davis; Altaf Saadi, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; Maria‑Elena De Trinidad Young, UC Merced; and Konrad Franco, UC Davis

The USA maintains the world’s largest immigration detention system. In two recent studies, we examined the health of detained immigrants in California during detention and following release.

In the first study, we examined confinement conditions (including sleep deprivation, social isolation from family via barriers to visitation, witnessing or experiencing abuse or harassment, and barriers to needed physical and mental health care) and found that each condition increased the likelihood of deleterious physical and/or mental health conditions among study participants.

The second study followed a group of participants after their release from detention and found that participants reported fewer physical, psychological, and overall symptoms of stress, as well better overall general health, compared to while they were detained.

Our findings suggest that while policies seeking to improve specific conditions in immigration prisons may address some risks of harm, ending the use of imprisonment in immigration law is likely to be most effective in mitigating the harmful health consequences of immigration detention.

Key Facts

- Conditions of confinement in immigration prisons negatively impacted detained immigrants’ physical and mental health.

- Following their release, former detained immigrants reported fewer physical, psychological, and overall symptoms of stress, as well as better general health, compared to while they were detained.

- Policies that prioritize an end to the use of imprisonment in immigration legal proceedings are likely to be most effective in mitigating the harmful health consequences of this system.

Stress and Worsening Health During Detainment

Our first study examined the association between conditions of confinement in immigration prisons and physical and mental health conditions among study participants.[1] We drew on data from the Rodriguez Study, the only existing survey of detained people in the U.S. that captures information about health and conditions of confinement.[2] We assessed (1) the prevalence of exposure to six conditions of confinement (sleep deprivation, social isolation from family via barriers to visitation, witnessing or experiencing abuse or harassment, and barriers to needed physical and mental health care); (2) the extent to which each condition of confinement was associated with physical and psychological stress, diagnosed mental health conditions, overall health, and perceived declines in general health, accounting for control variables; and (3) the cumulative impact of the confinement conditions on these outcomes, also accounting for control variables.

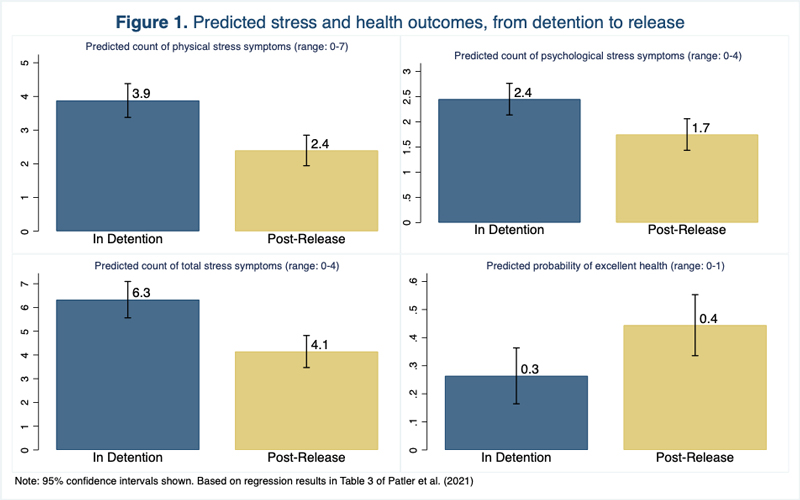

Participants experienced an average of three confinement conditions while detained. Each condition of confinement was independently associated with one or more negative health outcomes. For example, sleep deprivation, difficulty accessing medical services, and difficulty accessing mental health services were associated with higher stress, poorer overall health, and worse perceived health while in detention. There was also a cumulative effect to these conditions: For each additional confinement condition, the odds of reporting good health decreased by 24 percent, the odds of worsening general health rose by 39 percent, the odds of having had a mental health diagnosis increased by 25 percent, and reports of stress rose by 15 percent (see Figure 1).

Improved Health Following Release

The second study assessed the association between release from immigration prison and health outcomes including stress and overall health, compared to during detention. In this study, we analyzed two waves of Rodriguez Study from a subset of 79 study participants who were released on bond in the United States.[3] We compared physical and psychological stress, and overall physical health during detention and post-release.

Following their release, study participants reported lower stress and better overall health, compared to during detention (see Figure 1). Seventy percent of study participants reported fewer stress symptoms after release, compared to during detention. The predicted count of physical, psychological, and overall stress symptoms fell by 38 percent, 29 percent, and 35 percent, respectively, after release, compared to during detention. The predicted probability of having excellent health rose by 69 percent, compared to during detention.

To assess potential mechanisms influencing participants’ experiences of the benefits of release, we also examined responses to the open-ended question, “What is the best part about being out of detention?” Released participants overwhelmingly described the importance and positive impact of being reunited with family, being “free,” having “freedom” or “autonomy,” or being free from the controlled environment of detention as mechanisms for reduced stress and improved overall health. Other released immigrants described how being free enabled them to better fight their deportation cases and advocate for themselves.

Policy Focus: To Reduce Health Harms, Prioritize an End to Immigration Imprisonment

Our first study documented individual and cumulative associations between poor conditions of confinement and worsening general health, greater likelihood of mental health condition diagnosis, and increased stress symptoms. These findings provide evidence of the detrimental and cumulative impact of immigration prisons on health and indicate that detention can harm health via multiple potential pathways. Our second study found that release from immigration prison was associated with lower levels of psychological and physical stress and better general health. Given that anti-immigrant policies and immigration enforcement are associated with poor health outcomes,[4] understanding the health impacts of immigration prisons is critical to advancing health equity for immigrants.

Taken together, our results strongly support policies that end the use of imprisonment in immigration legal proceedings. Adjusting individual confinement conditions cannot adequately mitigate the multiple and cumulative harms of immigration prisons. However, we note that policy makers should not simply replace physical imprisonment with electronic surveillance, which other research suggest may invoke additional health harms.[5] To prioritize the health and wellbeing of detained immigrants, policy makers should release detained immigrants as their immigration legal proceedings are adjudicated.

Caitlin Patler is an associate professor of sociology at UC Davis. Altaf Saadi is an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. Maria‑Elena De Trinidad Young is an assistant professor of public health at UC Merced. Konrad Franco is a PhD candidate at UC Davis.

References

1. Saadi, A., Patler, C., & De Trinidad Young, M. 2022. Cumulative Risk of Immigration Prison Conditions on Health Outcomes Among Detained Immigrants in California. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 9, 2518–2532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01187-1

2. Patler C and Saadi A. 2021. Risk of poor outcomes with COVID-19 among U.S. detained immigrants: a cross-sectional study. J Immigr Minor Health. 23, 863–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01173-z

3. Patler, C., Saadi, A., De Trinidad Young, M., & Franco, K. 2021. Release from US immigration detention may improve physical and psychological stress and health: Results from a two-wave panel study in California. SSM – Mental Health. Volume 1, Article 10035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100035

4. Perreira KM, Pedroza JM. 2019. Policies of exclusion: implications for the health of immigrants and their children. Annu Rev Public Health. 40(1):147–66. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044115

5. Mirian G. Martinez-Aranda. 2022. Extended punishment: criminalising immigrants through surveillance technology. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 48:1, 74-91, DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1822159