Prosperity or Hardship: Equity-Driven Education Funding in the Era of COVID-19

By Patti F. Herrera, School Services of California, Inc., and Heather Rose, UC Davis

COVID-19 has created a $54 billion budget deficit for California. This has significant implications for K-12 school districts. It also has the potential to harm high-poverty districts more severely. To balance the budget while averting draconian education cuts, the state’s recently enacted 2020-21 budget defers nearly $11 billion of school district state aid. This forces districts to borrow in order to maintain staffing and educational programs. If not for the mitigating measures of recent federal relief programs, districts relying more heavily on state aid (such as those with larger shares of students who are low income, English learners, or foster youth) would be impacted more.

Key Facts

- California’s 2020-21 education budget defers nearly $11 billion of state aid payments to K-12 school districts, causing them to borrow funds to maintain educational programs.

- Districts with larger shares of students who are low-income, English Learners, or foster youth are more impacted by these deferrals.

- Federal aid programs help mitigate these distributional impacts, but not entirely.

The lion’s share of California’s school district revenue comes from Proposition 98’s guaranteed minimum spending level, which the state must meet each year. Proposition 98’s complex formulas are intended to protect education funding as a state budget priority. Prior to COVID-19, the 2019-20 budget enactment allocated $71.2 billion for K-12 education. However, falling state revenue from the ensuing economic shutdown caused the state’s K-12 education spending requirement to decline by $2.6 billion in 2019-20.[1] An even steeper decline is expected for the 2020-21 fiscal year, falling to $61.6 billion—13.5 percent less than the original 2019 budget.

What choices do lawmakers have when the minimum guarantee drops precipitously? The 2020-21 state budget, signed by Governor Newsom, recognizes the existing and growing costs that districts face in the wake of a learning crisis. This budget averts deep funding cuts and instead plans to defer over $11 billion in state aid. These deferrals shift state education spending from one fiscal year to the next (allowing the state to spend only $61.6 billion in 2020-21), while districts account for and budget the additional $11 billion in 2020-21, thus avoiding programmatic cuts. To meet monthly obligations, districts will likely borrow money, using the promise of late payments as collateral, incurring administrative and interest costs to do so.

The Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) determines how most Proposition 98 funding is allocated across the state’s nearly 1,000 K-12 districts. It is also, at 76 percent, the largest revenue source of district general fund revenue. Through supplemental and concentration (S&C) grant funding, LCFF explicitly allocates more per-pupil revenue to districts educating larger shares of students who are low-income, English learners, or foster youth, which we call LI/EL students.[2] While the LCFF determines every district’s entitlement, the mix of local property taxes and state aid differs across districts. After accounting for the local property taxes that districts receive, any balance of their LCFF funding entitlement is filled by aid from the state’s general fund. About $9 billion of deferrals apply to this state aid.[3]

Districts with larger shares of LI/EL students tend to rely more heavily on state aid and could be disproportionately impacted by deferrals. To mitigate this, the budget directed $5.3 billion in federal Learning Loss Mitigation (LLM) funds to school districts. The largest share, $2.86 billion, is distributed proportional to the S&C funding received by districts. Another $1.5 billion is based on the number of students with disabilities (SWD), and $0.98 billion is allocated proportional to a district’s LCFF funding. Additionally, the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) fund provides districts $1.5 billion, allocated according to the number of students qualifying for federal Title 1 funds.[4] This brief examines the distributional impact of deferrals and how the allocation of federal funding may offset these impacts.

Examining the Impact of Budget Deferrals

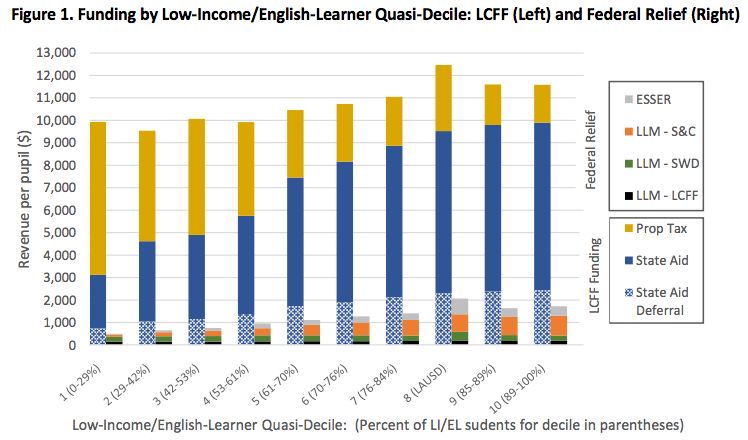

We ranked all California school districts according to the percentage of LI/EL students and divided them into ten groups, each containing roughly 10 percent of students.[5] Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) enrolls over 8 percent of statewide students, so was in its own group. Each quasi-decile below LAUSD enrolls roughly 10.5 percent of the state’s students; each quasi-decile above LAUSD enrolls about 9 percent of students. We used the last year of available Standardized Account Code Structure Data (2018-19) to plot average LCFF funding, broken down into property tax revenue and general state aid (Figure 1).[6] To provide an idea of the differential impact of a $9 billion deferral to 2018-19 LCFF funds, we shaded the portion of LCFF funding subject to the deferral. We also plotted the average expected funding from each of the federal relief programs.[7] Funding for each quasi-decile comprises total funding for all the districts in that decile divided by total students (Average Daily Attendance) in those districts.

Certain Districts Are at Risk of Greater Strain

Districts with more LI/EL students receive more LCFF funding, with a much higher percentage coming from general state aid rather than property tax. Districts in the lowest decile receive about $9,900 per pupil of LCFF; districts in the highest decile receive over $11,500 per pupil. General state aid comprises nearly 85 percent of LCFF funding for districts in the highest two deciles and less than 50 percent in the lowest two deciles. This composition of LCFF funding puts districts with higher shares of LI/EL students at risk of fiscal strain due to state aid deferrals.

Some of the disproportionate strain may be mitigated by federal relief funds. Most notably, districts with higher shares of LI/EL students will receive more per-pupil funding primarily from the ESSER and Learning Loss Mitigation funds allocated based on S&C funding. These latter funds provide nearly $900 per pupil in Decile 10 districts and only $100 per pupil in Decile 1. The ESSER funds provide over $400 in Decile 10 and only about $40 in Decile 1. The other two federal programs are allocated more equally per pupil.

Deferring Now Will Have Fiscal Repercussions Later

The state’s use of deferrals has, at least temporarily, partially immunized school districts from the COVID-19-induced budget cuts. Nonetheless, districts with more LI/EL students are at risk of being more impacted by these deferrals, which come at a time when local budgets are already strained. In 2015-16, only 14 districts were identified as struggling to meet their financial obligations within three years. Today, that number has nearly tripled.[8] Major cost drivers include the historic declines in student enrollment that reduce revenues for many districts and growing pension obligations that have increased by 68 percent since 2013.[9] The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened existing problems, sending districts scurrying to prevent deep learning losses from school closures and a systemwide migration to online learning, both of which have been unevenly implemented across and within districts.

Federal relief funds may partially offset deferrals, but several conditions may diminish their usefulness. Firstly, the federal relief funds have more strings attached. Secondly, they may just make up for costs already incurred by districts. Finally, they are subject to tighter spending deadlines than general state aid. The fiscal gymnastics of deferrals can certainly help districts temporarily. But if the state’s recession is prolonged and funding is eventually cut rather than deferred, districts may ultimately need to lay off staff and cut educational programs. If, as state finances improve, the state decides to pay down deferrals, doing so won’t translate into increased district spending. Rather, it will equate to paying off debt borrowed from districts. Although districts regularly engage in short-term borrowing to manage cash flow—a process made more palatable by historically low interest rates—borrowing costs and their distributional impact must be scrutinized going forward to ensure that state fiscal decisions do not undo the equity progress California has made since the Great Recession.

Patti F. Herrera is Associate Vice President at School Services of California, Inc. She completed her Doctorate in Education at the University of California, Davis.

Heather Rose is an Associate Professor in the School of Education at the University of California, Davis. Her research focuses on school finance policy.

Notes and References

[1] The 2019-20 and 2020-21 Proposition 98 revenue revisions come from the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

[2] The state does not double-count students if they are in more than one category and often refers to this group as the unduplicated pupil count. Low-income refers to students eligible for the free- or reduced-price meals program. All foster youths qualify for this program.

[3] Deferrals apply to principal apportionment funds from the state. About 81 percent of those are LCFF funds, so we attributed that share of the total deferral to LCFF state aid. (About 11 percent of apportionment funds go to charter schools; and 8 percent are special education funds.)

[4] Title 1 is a federal program that allocates funding based on the number of low-income students in a district.

[5] We used the 2018-19 Unduplicated Pupil Count (UPC) Source File data from the California Department of Education. We excluded charter schools and districts from this analysis.

[6] Property tax includes object codes 8021-8099; general aid includes object codes 8011-8019. The deferral applies only to the state apportionment (8011) of that general aid and is 29% of that apportionment. We computed the deferral for each district as 29% of its state apportionment. (State apportionment is about 80 percent of general state aid.)

[7] We thank Dave Heckler at School Services, Inc. for providing these federal data. We set SWD funding to zero if a district receives less than $18,867 in total SWD funds.

[8] Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team, Certifications of Financial Reports, California School Districts and COEs – 2007 to Present, https://www.fcmat.org/PublicationsReports/Certification-of-Budgets-chart-4-23-2020.pdf

[9] Legislative Analyst’s Office, The 2020-21 Budget: School District Budget Trends, https://lao.ca.gov/reports/2020/4136/school-district-budget-012120.pdf