Mothers Experience Greater Food Insecurity When Children Age Out of WIC

By Marianne Bitler, UC Davis; Janet Currie, Princeton University; Hilary W. Hoynes, UC Berkeley; Krista J. Ruffini, Georgetown University; Lisa Schulkind, University of North Carolina at Charlotte; Barton Willage, University of Colorado Denver

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) has been shown to improve birth outcomes. When they reach the age of five, however, children become ineligible to receive it. In a recent study, we examined, for both adults and children, the nutritional and laboratory outcomes of this age-related loss of eligibility. We found little impact on children who aged out of the program, but adult women experienced reduced caloric intake and increased food insecurity. This suggests that mothers protect children by consuming less themselves when WIC benefits are lost. Policymakers should consider these findings when evaluating the impact of WIC and programs like it.

Key Facts

- When children in the U.S. reach the age of five, they become ineligible to receive food vouchers through WIC.

- Aging out of WIC has no significant effect on food insecurity or caloric intake among children.

- Women in households where a child has aged out of WIC experience greater food insecurity and lower caloric intake as they protect the children in the household from the loss of WIC support.

Background

WIC is one of the most widely used U.S. food assistance programs, with nearly half of all infants participating. In 2021, the program served 6.2 million people at a cost of $5.0 billion.[1] WIC provides vouchers that can be used to purchase specific nutritious foods. It also mandates nutritional education and provides referrals to other programs.

People eligible for WIC include pregnant, post-partum, or nursing mothers/persons; infants; and children younger than five. Participants must have household incomes less than 185 percent of the federal poverty line or participate in Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Participants must also be “at nutritional risk,” but in practice, most applicants are deemed at risk. WIC participants face a “cliff”: recipients receive the full WIC package unless and until they lose eligibility. Immigrants are eligible for WIC under the same circumstances as citizens.

Some previous studies have found that food insecurity and food-bank utilization increased when children age out of WIC eligibility, while others have found no such effects.[2,3,4] In our study, we explored the spillover effects of child WIC participation on other family members’ food consumption, biomarkers, and food security. Specifically, we examined changes in these factors when the focal child aged out of WIC eligibility by turning five.[5]

Examining the Effects of Children Aging Out of WIC

Our data on consumption and health outcomes came from the NHANES III, conducted from 1988 through 1994, and from the continuous NHANES, conducted from 1999 and 2014. These nationally representative data are the main source of information about the health and nutritional status of American adults and children. In addition to interviews, these data draw on physical examinations and, for selected household members, laboratory tests providing health and nutrient measures.

We analyzed three main samples: one for “focal” children, and one each for adult women or older children who were selected for interview from the same households. To examine the magnitude of the decline in WIC participation at the 5-year cutoff, we used WIC Participant and Program Data (PC) from 1996-2016. We also used the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to examine whether participation in other means-tested assistance also changes at the end of the month when children turn five.

Loss of Eligibility Impacts Women in the Household More Than Children

Regarding the effects of aging out of WIC for children ages 3 to 7, we identified only small changes in nutrition: an increase of 9 calories relative to the mean of 1,676 calories per day. We also found the effects on food insecurity to be small and statistically insignificant. Our results strongly suggest that children were not changing their consumption of a key WIC package ingredient (milk), overall calories, or nutrients as measured by biomarkers.

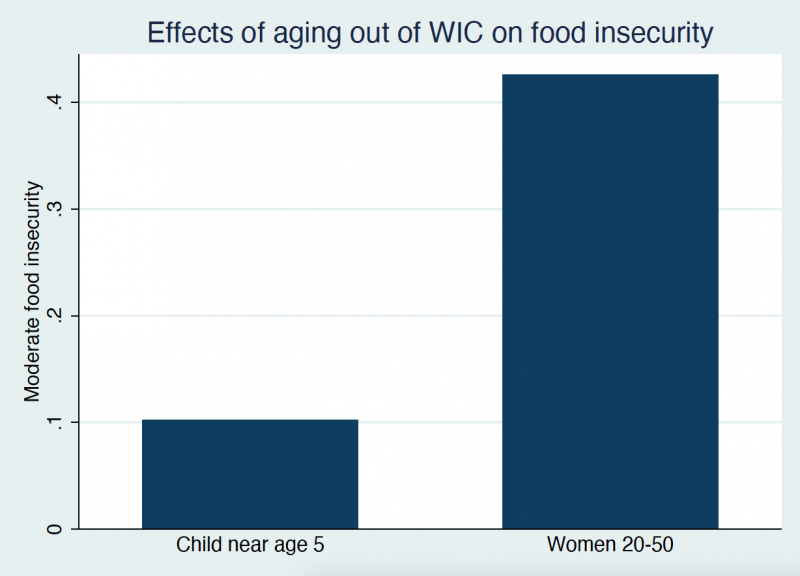

However, when we examined the impact of a child aging out of WIC on the sample of adult women 20 to 50 who live in the same household as the child, we found large increases in both severe and moderate food insecurity (see figure). We also found large and significant reductions in adult calories.

Mothers Shield Children from Consequences of WIC Eligibility Loss

We found no immediately measurable impact on the nutritional outcomes of the children who aged out of WIC. However, this may be because adult women in the household (who in many cases are their mothers) reduce their own consumption in order to buffer children from the consequences of losing access to WIC benefits.

Our results suggest that when the household loses WIC benefits, mothers ensure that children’s consumption does not suffer. They do this by consuming less themselves, thereby providing insurance to their children. There are no impacts on other demographic groups in the household such as older siblings. These results shed light on the ways households cope with the loss of resources from WIC: Mothers reduce their own consumption in a way that protects their children. Policymakers should consider these findings when assessing the impact of WIC and similar programs, since they make clear that WIC benefits entire households, not simply the children eligible to receive it.

Marianne Bitler is a professor of economics at the University of California, Davis. Janet Currie is Henry Putnam Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton University. Hilary W. Hoynes is Haas Distinguished Chair in Economic Disparities and Professor of Economics and Public Policy at UC Berkeley. Krista J. Ruffini is an assistant professor of economics at Georgetown University. Lisa Schulkind is an associate professor of economics at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Barton Willage is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Colorado Denver.

This research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Evidence for Action Program (grant #75116). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Foundation.

References

1. U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2022. WIC Data Tables. fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program. Accessed 28 March 2022.

2. Arteaga, I., Heflin, C., and Gable, S. 2016. The impact of aging out of WIC on food security in households with children. Children and Youth Services Review, 69, 82–96.

3. Si, X. and Leonard, T., 2020. Aging Out of Women Infants and Children: An Investigation of The Compensation Effect of Private Nutrition Assistance Programs. Economic Inquiry, 58(1), pp.446-461.

4. Smith, T. and Valizadeh, P. 2018. Aging out of WIC and Child Nutrition: Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design. Working paper.

5. Bitler, M., Currie, J., Hoynes, H.W., Ruffini, K.J., Schulkind, L., and Willage, B. 2022. Mothers as Insurance: Family Spillovers in WIC. NBER Working Paper 30112. DOI 10.3386/w30112.