More Unhealthy Products Promoted at Checkouts in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods

By Samantha Marinello and Lisa M. Powell, University of Illinois Chicago; and Jennifer Falbe, University of California, Davis

Food companies pay to ensure their products are displayed at store checkouts, where they are more likely to trigger impulse purchases and child purchasing requests. These products, such as candy, chips and sugar-sweetened beverages, are mostly unhealthy. The first jurisdiction globally to implement a healthy checkout policy is Berkeley, California.

In a recent study, seeking to understand the potential for policies such as Berkeley’s healthy checkout ordinance (HCO) to promote equitable food environments, we examined associations between store neighborhood characteristics and healthfulness of foods and beverages offered at checkout. We found that neighborhoods with lower socioeconomic status (SES) and higher Black and Hispanic residential composition had a higher prevalence of foods and beverages that did not meet HCO standards.

These findings suggest, firstly, that the checkout environment may be one of many contributors to diet-related health disparities, and secondly, that healthy checkout policies may have the potential to increase nutrition equity by improving food environments across neighborhoods, particularly in areas with lower SES and higher Black and Hispanic composition.

Key Facts

- Checkout displays intended to trigger impulse purchases promote mostly unhealthy foods and beverages.

- Unhealthy products were more widely promoted at store checkouts in neighborhoods with lower socioeconomic status and larger Black and Hispanic populations.

- Healthy checkout policies like the one implemented in Berkeley, California may help to increase nutrition equity by improving access to healthier products at store checkouts, particularly in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Background

Populations disproportionately affected by diet-related diseases, including Black, Hispanic, and lower-SES communities, are also more likely to live in unhealthy food environments. These environments are characterized by lower availability of healthy foods and higher exposure to unhealthy food marketing.[1,2] In-store marketing and product placement in retail food stores has been shown to influence consumer purchases of both healthy and unhealthy foods and beverages.[3,4] Many large food companies pay “slotting fees” to place mostly unhealthy products at store checkouts.[5,6] This is concerning because nearly one-third of adults purchase items at checkout once or more per week. Those most likely to do so are Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native adults, adults with lower incomes, and parents.[7]

In March 2021, Berkeley, California implemented the world’s first healthy checkout ordinance (HCO) to ensure that food stores “offer healthy options and do not actively encourage the purchase of unhealthy foods.”[8] The HCO states that at checkout large retail food stores in Berkeley can offer non-food items, unsweetened beverages, and specific categories of foods containing low sugar and sodium. In our study, we used product facing data from food-store checkouts in Berkeley and three other Northern California cities to examine associations between neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics and the healthfulness of checkout products to describe racial, ethnic, and SES differences in exposure to unhealthy food environments.[9]

Examining Associations Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Unhealthful Checkouts

We used data about products facing consumers at checkout at 102 California food stores in Berkeley, Oakland, Davis, and Sacramento. These data were collected one month prior to the implementation of the HCO. A reliable photo-based tool was used to record information on all product facings at up to three checkouts per store. The three comparison cities were selected based on their similar urbanicity, racial and ethnic diversity, and economic indicators to Berkeley.[10] Our final sample included 26,758 facings.

Several store-level outcomes were calculated, including the percentage of food and beverage facings that did not meet HCO standards, the percentage of beverage facings that were sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), the percentage of beverage facings that were water, and the percentages of food facings that were sweets, salty snacks, and healthy foods respectively.

To analyze these data, we calculated summary statistics on checkout and neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics across all stores. To illustrate the magnitude of the associations between each outcome and explanatory variable, we used models to predict values of percentage of food and beverage facings not meeting standards for the lowest and highest quartiles (at quartile median) of poverty, percentage Black, and percentage Hispanic neighborhood characteristics.

Unhealthy Checkouts More Prevalent in Low-SES Neighborhoods

We found that 70 percent of foods and beverages in our sample did not meet HCO standards. SSBs were more prevalent than water at checkout (52 percent vs. 16 percent of beverages), and sweets were more prevalent than healthy foods (48 percent vs. 7 percent of foods). We also found that higher poverty, lower educational attainment, and higher Black and Hispanic compositions of neighborhoods were associated with a higher prevalence of non-HCO-compliant foods and beverages at checkout. In contrast, stores in neighborhoods with a higher White composition had a higher prevalence of checkout foods and beverages that met HCO standards.

Regarding beverages, higher poverty and Hispanic composition were associated with a higher prevalence of SSBs at checkout. Stores in neighborhoods with higher poverty and Multiracial composition were less likely to offer water at checkout. Regarding foods, higher poverty, lower educational attainment, and higher Black and Hispanic compositions were associated with a higher prevalence of sweets at checkout, whereas higher neighborhood White composition was associated with a lower prevalence of sweets at checkout. Neighborhoods with more children, higher poverty, lower educational attainment, and higher Hispanic composition were less likely to have healthy checkout foods, while neighborhoods with a higher White composition were more likely to have healthy checkout foods.

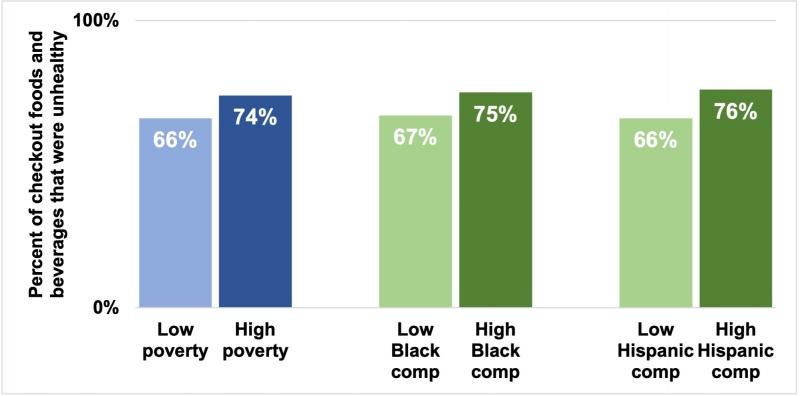

Stores in neighborhoods with a high vs. low poverty rate had a 12 percent relative higher prevalence of foods and beverages not meeting HCO standards (see Figure 1). Stores in neighborhoods with a high vs. low Black and Hispanic composition had a 12 percent and 15 percent, respectively, relative higher prevalence of non-HCO-compliant food and beverage facings.

Figure 1: Unhealthy foods and beverages at checkouts in different neighborhoods

Improve Food Environments Across All Neighborhoods to Increase Nutrition Equity

Across all neighborhoods, most foods and beverages at checkout were unhealthy. However, neighborhoods with lower SES and a higher percentage of Black and Hispanic residents had a higher prevalence of unhealthy foods and beverages, particularly sweets and/or SSBs, at checkout. These neighborhoods were also associated with a 12-15 percent relative higher prevalence of foods and beverages that did not meet HCO standards. Neighborhoods with more children, lower SES, and a higher percentage of Hispanic residents had a lower prevalence of healthy checkout foods.

Our findings suggest that checkout environments may be one of many contributors to nutrition and health disparities by SES, race, and ethnicity. It follows that healthy checkout policies have the potential to increase nutrition equity by improving food environments across neighborhoods and especially in areas with a lower SES and higher Black and Hispanic composition.

Samantha Marinello is a postdoctoral research associate in the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois Chicago.

Lisa M. Powell is a Distinguished Professor and Director of the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois Chicago.

Jennifer Falbe is an associate professor of nutrition and human development at the University of California, Davis.

References

1. Zenk S.N., Powell L.M., Rimkus L., Isgor Z., Barker D.C., Ohri-Vachaspati P., Chaloupka F. Relative and absolute availability of healthier food and beverage alternatives across communities in the United States. Am. J. Public Health. 2014. 104(11):2170–2178. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302113

2. Powell L.M., Wada R., Kumanyika S.K. Racial/ethnic and income disparities in child and adolescent exposure to food and beverage television ads across the U.S. media markets. Health Place. 2014. 29:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.06.006

3. Hecht A.A., Perez C.L., Polascek M., Thorndike A.N., Franckle R.L., Moran A.J. Influence of food and beverage companies on retailer marketing strategies and consumer behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020. 17(20):7381. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207381

4. Almy, J., & Wootan, M. G. Temptation at checkout: the food industry’s sneaky strategy for selling more. 2015. Accessed 12/1/2022. https://www.cspinet.org/temptation-checkout

5. Cohen D.A., Babey S.H. Contextual influences on eating behaviours: heuristic processing and dietary choices. Obes. Rev. 2012. 13(9):766–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01001.x

6. Falbe J., Marinello S., Wolf E.C., Solar S.E., Schermbeck R.M., Pipito A.A., Powell L.M. Food and beverage environment s at store checkouts in California: mostly unhealthy products. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2023. 7(6) doi: 10.1016/j.cdnut.2023.100075

7. Falbe J., White J.S., Sigala D.M., Grummon A.H., Solar S.E., Powell L.M. The potential for healthy checkout policies to advance nutrition equity. Nutrients. 2021. 13(11):4181. doi: 10.3390/nu13114181

8. Berkeley, CA Ordinance 7734-NS, 2020

9. Marinello S., Powell L.M., Falbe J. Neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics and healthfulness of store checkouts in Northern California. Prev Med Rep. 2023. Aug 22; 35:102379. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102379

10. U.S. Census Bureau. 2016-2020 5-Year American Community Survey. Accessed 11/3/2022. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/