Longer WIC Participation Contributes to Healthier Diets Among Young Children

By Lauren E. Au, UC Davis; Hannah R. Thompson, UC Berkeley; Lorrene D. Ritchie, UC ANR; Brenda Sun, Thea P. Zimmerman, Westat; Shannon E. Whaley, PHFE WIC; Amanda Reat, Westat; Kavitha Sankavaram, USDA; and Christine Borger, Westat

In a recent study, we examined the extent to which foods and beverages available in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Food Package help to improve the quality of young children’s diets.

To do so, we used diet quality from Healthy Eating Index-2020 scores in conjunction with data related to WIC participation among children aged 2 to 5.

We found that children with high WIC duration had higher total HEI-2020 scores compared with children with low WIC duration.

Our findings suggest that when young children participate in WIC for longer, their diets are better aligned with national dietary guidelines.

Policymakers should consider how WIC participation contributes positively to dietary quality when contemplating potential changes to the program.

Key Facts

- The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) serves more than 6.7 million low-income people in the U.S. each year.

- Longer participation in WIC contributes to higher diet quality among infants and young children.

- By aligning WIC food packages with the latest Dietary Guidelines for Americans, policymakers can maximize the availability of healthy foods for disadvantaged children.

Background

WIC is the third largest federal nutrition assistance program in the US, serving more than 6.7 million people in the U.S. each year.[1] It has been widely recognized as a cost-effective program that supports healthier pregnancies, better diets, and stronger links to social services for families with limited income.[2]

One of its core benefits is a monthly package of nutrient-rich foods designed to meet the specific needs of infants and young children. While these packages do not provide all of a participant’s dietary needs, they play a major role in improving nutrition.[3] Congress requires that WIC food packages be updated once every decade.[4] The last major revision came in 2009, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture adjusted them to match national dietary guidelines, adding whole grains and low-fat or non-fat dairy. A cash-value benefit for the purchase of fruits and vegetables was also added.[5,6]

WIC offers nutrition education, tailored to families and based on the latest Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA).[7] Studies show that children in WIC have higher diet quality, greater food security, and better health than similar children who do not participate. Research also suggests that the longer a child participates in WIC, the better their diet quality. For example, WIC-approved foods often make up nearly half of young children’s calories and nutrients. Our study[8] aimed to build on that evidence by examining how WIC participation and food choices shape the diets of children aged 2 to 5, and how well these diets align with national nutrition goals.

Examining the effects of WIC participation on diet quality

We analyzed data from the WIC Infant and Toddler Feeding Practices Study-2 (WIC ITFPS-2), a nationally representative study that collected 24-hour dietary recall and sociodemographic information on young children at repeated intervals over the first 5 years of life, between 2013 and 2019. Participants for WIC ITFPS-2 were recruited from 80 locations across 27 WIC state agencies. Our sample for analysis comprised 980 infants and young children. We assessed the duration of their WIC participation, and used the HEI-2020—which stipulates healthy foods like greens and beans, while also highlighting unhealthy ones like sodium—to assess participants’ dietary quality between the ages of 2 and 5.

Longer WIC participation contributed to higher HEI scores

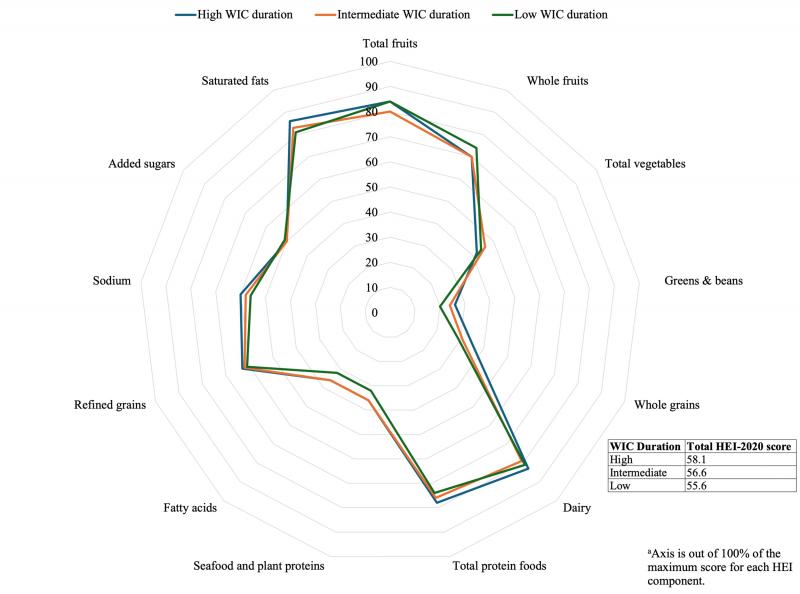

We found that 43 percent of the study sample participants were in the high duration group, 47 percent were in the intermediate duration group, and 10 percent were in the low duration group. The high-duration group had significantly higher total HEI-2020 scores compared with the low-duration group (58.1 vs 55.6), although the differences in total HEI-2020 component scores did not differ between groups.

Many of the WIC-eligible foods contributing to HEI-2020 component scores were higher in the high-duration group compared with the low-duration group, including higher intake of dried beans and peas (14 percent vs 5 percent), not presweetened breakfast cereals (24 percent vs 10 percent), and low-fat milk (24 percent vs 3 percent). The high-duration group also demonstrated lower average intake of sweetened breakfast cereals (15 percent vs 26 percent) and reduced-fat milk (11 percent vs 29 percent) compared with the low-duration group.

Figure 1. Radar plot showing the Healthy Eating Index (HEI)-2020 component scores by WIC duration in the Infant Toddler Feeding Practices Study-2.[a]

Promote WIC participation to improve the diets of disadvantaged children

WIC-eligible foods contributed to differences in overall HEI-2020 scores, showing a greater contribution in the high-duration group compared with the low-duration group. Participants in the high-duration group consumed more dried beans and peas, unsweetened breakfast cereals, whole-grain breads, and low-fat milk; and had lower intake of sweetened breakfast cereals and reduced-fat milk. These findings illustrate how WIC-eligible foods are driving higher overall diet-quality scores. These differences may be attributable to access to healthier foods in the WIC food package and nutrition education provided by WIC.

Differences in dietary intakes over a large population for a relatively long period of time may result in substantial differences in health outcomes.[9] In addition, WIC is a supplemental program and does not provide all foods needed for children to meet dietary guidelines, so small differences are particularly meaningful. Although recent data suggest that economic disparities in dietary quality are increasing in the US,[10] our findings suggest that longer duration on WIC can ameliorate disparities in access to nutritious foods. Improving WIC participation, by potentially targeting both WIC enrollment and continued participation in the program, may improve diet quality over time.

When participants stay with WIC longer, their diets are better aligned with the DGA. In addition, this study highlights how the specific nutrient-dense foods provided in the WIC food packages are consumed considerably more by children who continue to receive them through their ongoing participation in the program. Together, these findings provide evidence for policymakers about the importance of consistently aligning WIC food packages with the DGA to maximize the availability of healthy foods for children in households with low incomes.

Lauren E. Au is an associate professor in the Department of Nutrition at UC Davis.

Hannah R. Thompson is an assistant research professor in the Department of Public Health at UC Berkeley.

Lorrene D. Ritchie is a cooperative extension nutrition specialist emeritus at UC Agriculture and Natural Resources.

Brenda Sun is a senior analyst at Westat.

Thea P. Zimmerman is a senior study manager at Westat.

Shannon E. Whaley is director of research and evaluation at PHFE WIC.

Amanda Reat is a social science research analyst at the USDA.

Kavitha Sankavaram is an analyst at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Christine Borger is a principal research associate at Westat.

References

1. WIC data tables. US Department of Agriculture. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program

2. About WIC: How WIC helps. US Department of Agriculture. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic-how-wichelps

3. Changes to the WIC food package Q&As. Accessed July 22, 2024. US Department of Agriculture. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/foodpackages/qas

4. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Review of WIC Food Packages: Improving Balance and Choice: Final Report. National Academies Press; 2017.

5. US Department of Agriculture, US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2005. 6th ed. US Government Printing Office; 2005.

6. Background: Revisions to the WIC food package. US Department of Agriculture. Accessed July 22, 2024. www.fns.usda.gov/wic/foodpackages/background-revisions#

7. US Department of Agriculture, US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Accessed November 29, 2024. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf

8. Au LE, Thompson HR, Ritchie LD, Sun B, et al. Longer WIC Participation Is Associated with Higher Diet Quality and Consumption of WIC-Eligible Foods Among Children 2-5 Years Old. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2024. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2024.11.012

9. Herman PM, Nguyen P, Sturm R. Diet quality improvement and 30-year population health and economic outcomes: A microsimulation study. Public Health Nutr. 2021;25(5):1-9.

10. Wang Y. Disparities in pediatric obesity in the United States. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(1):23-31.