Lessons Learned from Implementing a Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax in Berkeley, California

By Jennifer Falbe, UC Davis; Anna H. Grummon, Harvard University; Nadia Rojas, ChangeLab Solutions; Suzanne Ryan-Ibarra, Public Health Institute; Lynn D. Silver, Public Health Institute; and Kristine A. Madsen, UC Berkeley

In 2014, Berkeley, California became the first US jurisdiction to tax distribution of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs). In a recent study, we interviewed city stakeholders and SSB distributors and retailers and analyzed records in order to identify lessons learned from the implementation of this tax. Our findings emphasized the importance of investing tax revenues back into the community through programs that advance health equity. Other findings include the need for thorough and timely communications with distributors and retailers, adequate lead time for implementation, advisory commissions for revenue allocations, and funding of staff, communications, and evaluation before tax collection begins. We concluded that the policy package, context, and implementation process facilitated translating policy into public health outcomes, and that the Berkeley example could, and should, inform the success of future taxes. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need to fund public health and food security is more pressing than ever. SSB taxation not only contributes to reducing risk factors for severe COVID-19 illness, such as type 2 diabetes, but also generates revenues that can support the families and communities hit hardest by the pandemic.

Key Facts

- Policymakers and public health experts have argued that the sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) industry should be taxed for the health-harms their products cause, and that revenues should fund public health programs, especially ones that address health disparities.

- Berkeley’s SSB tax ordinance generated more than $9 million, which was allocated for public health and equity from 2015 to 2021.

- Within one year, SSB consumption declined in Berkeley’s lower-income neighborhoods, and SSB purchasing dropped 10 percent in supermarkets.

- Key lessons include the importance of thorough and timely communications with business, adequate lead time for implementation, and the need to immediately fund new staff, communications, outreach, and evaluation before implementation.

The Berkeley ordinance, which garnered 76 percent of the vote in a 2014 referendum and was implemented the following year, levied a $0.01 per ounce excise tax on SSB distribution. Although SSB taxes evoke higher support when revenues are designated for health or education, Berkeley’s measure appropriated revenues to the general fund. This was a strategic decision made by SSB tax proponents and City Council to keep the vote threshold at a simple majority, since California requires a two-thirds vote for earmarked taxes.[1] However, to promote revenue allocations aligned with public health, the ordinance established an SSB Product Panel of Experts (SSBPPE) to advise the city on funding “programs to further reduce [SSB] consumption. . . [and its] consequences.”

Within one year, SSB consumption declined in Berkeley’s lower-income neighborhoods,[2] and SSB purchasing dropped 10 percent in supermarkets.[3] These results are consistent with findings of lower consumption and sales of taxed beverages following enactment of beverage taxes in Mexico (in 2013), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (2016), and Seattle, Washington (2017). With eight further US jurisdictions now having implemented such taxes, the evidence base for SSB taxation has strengthened. Given this, it is critical to use implementation science to identify barriers, facilitators, and resources required to translate taxation policy into public health outcomes.[4]

Support, Simplicity, and Synergy

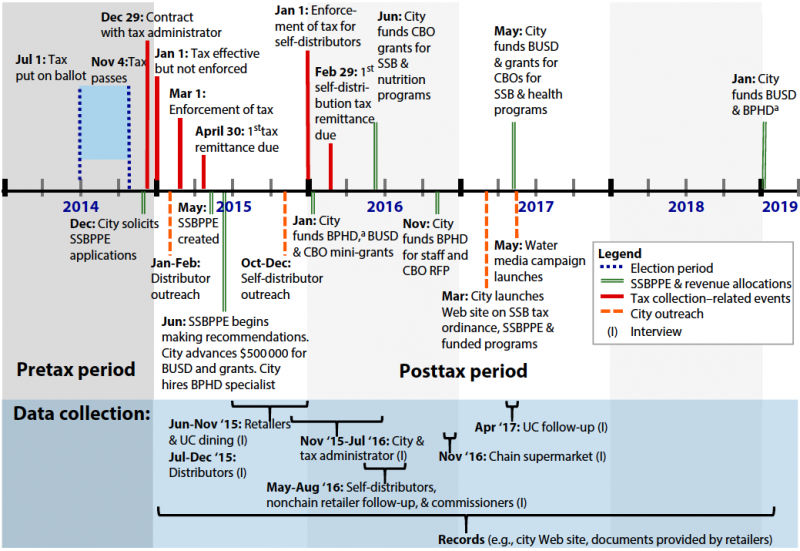

From June 2015 to April 2017, we conducted 48 semi-structured interviews with city staff, its tax administrator, SSB distributors, Berkeley retailers, and SSBPPE commissioners. We audio-recorded interviews and transcribed them verbatim, or took detailed notes when subjects declined recording, and used both deductive and inductive analysis to interpret our results. We analyzed these data using implementation science frameworks.

In our study[5], we identified three policy characteristics that facilitated implementation of Berkeley’s SSB tax. The first was the legitimacy of the policy source, based on the emphatic referendum result plus support for the tax from a diverse coalition including parents, health professionals, the Berkeley NAACP, Latinos Unidos, and others. The second was the simplicity of the tax calculation ($0.01/oz) when compared with, for example, tobacco tax rates, which vary from one product to the next. The third was the policy “package” that combined a tax with a community and expert advisory commission tasked with identifying the best uses for the revenue. These two components worked synergistically: the excise tax reduced SSB consumption while generating revenue which the commission directed to new public health programs.

In terms of outer setting, characteristics of Berkeley’s history, institutions, and residents were conducive to public support for SSB tax enactment and implementation. Meanwhile, the inner setting—City officials—placed a high priority on implementation. This took the form of early leadership engagement across multiple city departments, especially Finance, the City Attorney’s Office, and, later, Public Health, with leadership from the City Manager’s Office. A lesson learned in this area was the importance of funding and hiring personnel in advance of implementation.

Regarding implementation, Berkeley’s tax collection was divided into phases focusing on (1) distributors (e.g., Pepsi and Coca Cola bottling companies) and (2) self-distributors (e.g., retailers that make their own SSBs or buy SSBs from wholesale stores). City officials and the tax administrator perceived successful execution of the first phase, noting a wide-reaching communication strategy, high attendance at education sessions, and timely execution of tax collection.

The second phase (self-distributors) began in January 2016, 10 months after enforcement for distributors began. Though the city and the administrator engaged potential self-distributors in November 2015 through a mailing and phone call, inviting them to attend two education sessions. Although few attended, those who did found the sessions useful. Most self-distributors did not recall receiving mailed session notifications and said that e-mail and in-person visits were preferable modes of communication. Overall, a lesson learned from this phase was the need for more widespread outreach.

Retailers and Revenue

Although SSB distributors could assume the costs of the excise tax, most raised prices to retailers, according to interviews. When asked if and how retailers were making up for these costs, most reported raising SSB prices only, with some absorbing or delaying beverage price increases. No retailers reported raising food prices, indicating that beverage industry claims that SSB taxes are “grocery taxes” are false and deceptive . Many retailers regretted the lack of early retailer-specific outreach from the city, which contributed to some confusion about whether artificially sweetened drinks and sugar-sweetened coffee and fruit drinks were taxable. Many retailers were highly supportive of the tax, mentioning benefits for children or health. Approval was lower, however, among small retailers bordering other cities. Several of these wanted the tax to cover a larger jurisdiction, such as the whole state of California, so that they were not at a competitive disadvantage on price.

Regarding SSBPPE and revenue allocation, commissioners recommended getting money quickly to the community (which the City Council did by advancing funds before revenues accrued), and quickly funding a robust media campaign. Both actions would facilitate widespread understanding of the rationale for the tax and disseminate information on programs funded, which can sustain public support. Commissioners noted the importance of advisory commissions for making revenue allocations consistent with the intent of the law, ensuring that funded programs are within the scope of the ordinance and that new funding not replace existing funding.

Lessons for Future Implementations

Berkeley’s SSB tax ordinance generated more than $9 million in funding allocated for public health and equity from 2015 to 2021, facilitated by the SSBPPE Commission, which represented community and expert voices and provided accountability over revenue allocations. Key lessons from Berkeley include the importance of thorough and timely communications with business, adequate lead time for implementation, and the need to immediately fund new staff, communications, outreach, and evaluation before implementation. Early and robust outreach to the public and retailers about the tax and programs funded may promote public support, correct misinformation, educate residents about healthy beverage consumption, reduce friction, and facilitate any beverage price increases only on SSBs.

These lessons provide a starting place for other jurisdictions considering SSB taxes. The policy package, context, and implementation process, including stakeholder engagement, were key for translating tax policy into public health behavioral outcomes. However, more research is needed to understand the long-term facilitators and barriers to sustaining the public health benefits of Berkeley’s SSB tax, and also how those differ from facilitators and barriers in other jurisdictions, such as Philadelphia and Cook County, which faced aggressive industry-funded repeal campaigns.

Jennifer Falbe is Assistant Professor of Nutrition and Human Development at the University of California, Davis.

Anna H. Grummon is a David E. Bell Fellow at the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies and a research fellow at the Division of Chronic Disease Research Across the Lifecourse (CoRAL).

Nadia Rojas, formerly a research associate at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, is a Policy Analyst at ChangeLab Solutions.

Suzanne Ryan-Ibarra is a Principal Investigator and Senior Research Scientist at Survey Research Group, a program of the Public Health Institute.

Lynn D. Silver is a pediatrician and public health expert who serves as senior advisor at the Public Health Institute.

Kristine A. Madsen is Associate Professor at the School of Public Health and the Faculty Director for the Berkeley Food Institute.

References

[1] Hagenaars LL, Jeurissen PPT, Klazinga NS. The taxation of unhealthy energy-dense foods (EDFs) and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs): an overview of patterns observed in the policy content and policy context of 13 case studies. Health Policy. 2017;121(8):887–894.

[2] Falbe J, Thompson HR, Becker CM, Rojas N,McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Impact of the Berkeley excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1865–1871.

[3] Silver LD, Ng SW, Ryan-Ibarra S, et al. Changes in prices, sales, consumer spending, and beverage consumption one year after a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages in Berkeley, California, US: a before-and-after study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(4):e1002283.

[4] Global Food Research Program, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Multi-country obesity prevention initiative: resources. 2019. Available at: http://globalfoodresearchprogram.web.unc.edu/multi-country-initiative/resources. Accessed February 25, 2019.

[5] Falbe J, Grummon AH, Rojas N, Ryan-Ibarra S, Silver LD, Madsen KA. Implementation of the First US Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax in Berkeley, CA, 2015–2019. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(9):1429-1437. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305795