Increase Awareness and Enforcement of ‘Reporting Pay’ Policies to Mitigate Impacts of Precarious Work

By Ryan Finnigan and Savannah Hunter, University of California, Berkeley

Precarious work schedules, including last-minute cuts to workers’ shifts, undermine well-being for millions of workers and their families in the United States. In a recent study, we evaluated the extent to which labor regulations can moderate this precarity and its impacts.

We looked in particular at “reporting pay” policies, which require employers to pay workers for some portion of their shift if they report to work but the employer ends their shift much earlier than scheduled. To evaluate these policies, we surveyed hourly workers to measure self-reported and actual policy coverage, the frequency of “shift cuts”, and receipt of reporting pay following cut shifts.

We found compliance with reporting pay policies to be partial at best. We also found awareness of these policies to be extremely low among workers covered by them. More encouragingly, we found that providing information about reporting pay policies significantly increases recommendations that a hypothetical worker should push for compensation for a shift cut.

We conclude that state labor agencies should increase their proactive awareness and enforcement efforts, and that partnerships with key stakeholders could help deter violations of reporting pay and other labor laws.

Key Facts

- Intended to offset the impacts of precarious work schedules, “reporting pay” policies require employers to pay workers for some portion of their cut shifts.

- Compliance with reporting pay policies was partial at best, while awareness among workers covered by them was low.

- Proactive efforts should be made by state labor agencies to increase enforcement of these important policies.

Background

Precarious work schedules are increasingly common for workers in the US, particularly for low-wage workers in industries faced with volatile demand.[1,2] One facet of such schedules is “cut shifts”, which can substantially reduce hourly workers’ total earnings and increase earnings instability. In retail and food service, for example, unpredictable and unstable work schedules are the norm, with managers frequently sending employees home without pay when business is slow.[3,4]

Though the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) does not regulate schedule stability or predictability nationally, “reporting pay” policies do currently exist in eight states plus Washington, DC. These policies, and labor laws more broadly, rely on “bottom-up enforcement”, requiring workers to recognize their rights and advocate for themselves, either to their employer or to the state.[5] However, many workers are unaware of detailed labor regulations or how to file complaints, and many justifiably fear retaliation from employers.[6]

In our study[7], we sought to evaluate compliance with reporting pay policies and their enforcement processes; to assess workers’ awareness of and willingness to recommend enforcing reporting pay policies following a hypothetical violation; and to identify potential improvements in labor-policy enforcement.

Surveying Precarious Workers

We surveyed currently employed workers from across all 50 US States plus Washington, DC. Our sample included 1,233 hourly workers, with 14 percent covered by a reporting pay policy. Respondents answered questions about job characteristics, work schedules, experiences with cut shifts and wage theft, awareness of local reporting pay and minimum wage policies, and hypothetical scenarios involving cut shifts, underpayment and how they would recommend a worker respond. If respondents said they “sometimes” or “often” experienced shift cuts, we also asked how many times they experienced shift cuts in the last month. If respondents said they “sometimes” or “often” experienced shift cuts and they “sometimes” or “usually/often” received reporting pay, we also asked if they received reporting pay following their most recent shift cut. We also sought administrative data on complaints or citations for reporting pay violations from state labor departments.

Low Awareness and Enforcement Among Workers and Supervisors

We found that shift cuts were common but compliance with reporting pay policies was mixed. 32 percent (1,233) of all respondents experienced shift cuts at least sometimes. Among the 434 workers who self-reported experiencing cut shifts, 55 percent said they never received compensation, and only 23 percent said they usually or always received it. Overall, we found the probability of receiving compensation for shift cuts was much greater for workers covered by reporting pay policies than those not covered, but only when it came to receiving pay “sometimes”. This suggests partial compliance with reporting pay policies among employers. We also found that the probability of receiving compensation for shift cuts was greater for workers with higher amounts of required reporting pay by their state’s policy. However, we did not find that reporting pay policies disincentivized employers from cutting shifts, finding minimal evidence that shift cuts were less common among covered v. non-covered workers.

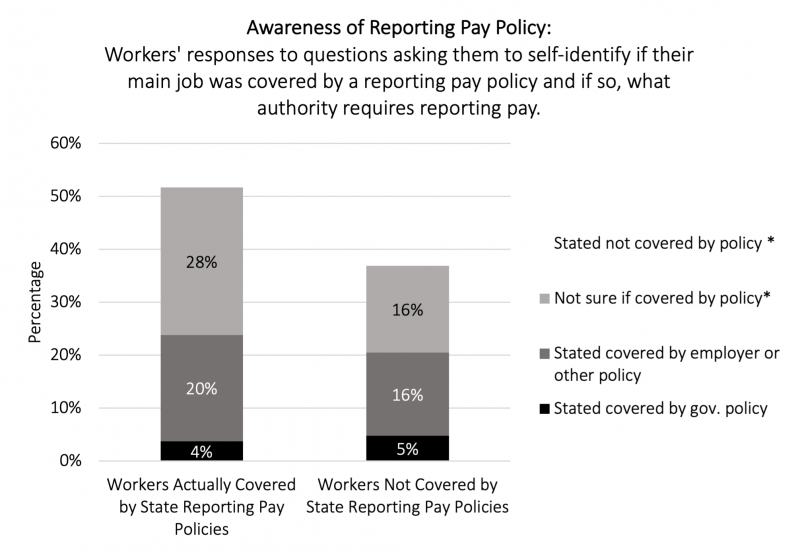

Note: Figured adapted from figure 3 in Finnigan and Hunter (2022).

We found explicit awareness of state reporting pay policies among workers to be very low, with only 4 percent of covered workers expressing knowledge of their coverage (see figure). Among supervisors, only 17 percent working in covered states knew about the presence of a state reporting pay policy. This level of awareness was lower than workers’ knowledge of the minimum wage, which one-third identified correctly.

Increase Policy Awareness and Bottom-Up Enforcement

Our results suggest only partial compliance with state reporting pay policies among employers. We also found no evidence that reporting pay policies discourage employers from cutting workers’ shifts short. Many covered workers reported uncertainty about their coverage, potentially indicating latent awareness of these policies—awareness that could be increased by proactive efforts from state labor agencies. Indeed, we found that workers’ recommendations to seek reporting pay owed after a shift cut were responsive to policy information, a precursor to changes in enforcement behavior. Raising awareness of reporting pay policies among employers and workers is an important first step toward improving enforcement.

Evidence from the ground is encouraging. For example, awareness and compliance are relatively high in Seattle, and workers’ schedule predictability and well-being there have improved.[8] In light of this, future awareness campaigns should include reporting pay and inform workers about the process for filing formal complaints to limit bureaucratic hurdles and encourage workers to pursue enforcement informally working with their employer or filing a complaint with a state department of labor.

Additionally, recognizing that workers face an imbalance of power relative to their employers and fear the consequences of speaking up, governments need to do more to empower workers to exercise their rights. Labor unions, worker centers, non-profits, and other worker-centered organizations are critical allies for empowering workers in pursuing enforcement [9] and could help deter violations of reporting pay and other labor laws, particularly given labor departments’ budgetary and capacity limitations. Given that reporting-pay-covered workers are disproportionately workers of color, immigrants, and in service occupations, more effective reporting pay policies could partly address related economic disparities.

Ryan Finnigan is a senior research associate at the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley.

Savannah Hunter is an associate research and policy specialist at the UC Berkeley Labor Center Low-wage Work Program.

References

1. Finnigan, R. 2018. Varying Weekly Work Hours and Earnings Instability in the Great Recession. Social Science Research. 74: 96–107

2. LaBriola, J. and Schneider, D. 2019. Worker Power and Class Polarization in Intra-Year Work Hour Volatility. Social Forces. 98 (3):973–99.

3. Schneider, D. and Harknett, K. 2019. Consequences of Routine Work-Schedule Instability for Worker Health and Well-Being. American Sociological Review. 84(1):82–114.

4. Halpin, B. 2015. Subject to Change without Notice: Mock Schedules and Flexible Employment in the United States. Social Problems. 62:419–38.

5. Charlotte, A. and Prasad, A. .2014. Bottom-Up Workplace Law Enforcement: An Empirical Analysis. Indiana Law Journal. 89(3):1069–132.

6. Bernhardt, A., Spiller, M.W. and Polson, D. 2013. All Work and No Pay: Violations of Employment and Labor Laws in Chicago, Los Angeles and New York City. Social Forces. 91(3):725–46.

7. Finnigan, R. and Hunter, S. 2022. Policy Regulation of Precarious Work Schedules and Bottom-Up Enforcement: An Evaluation of State Reporting Pay Policies. Social Forces. soab164. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soab164

8. Haley-Lock, A., Harknett, K., Harper, S., Lambert, S., Romich, J. and Schneider, D. 2019. The Evaluation of Seattle’s Secure Scheduling Ordinance: Year 1 Findings.” University of Washington West Coast Poverty Center. https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/CityAuditor/auditreports/SSO_EvaluationYear1Report_122019.pdf (Accessed February 20, 2021)

9. Fine, Janice and Jennifer Gordon. 2010. “Strengthening Labor Standards Enforcement through Partnerships with Workers’ Organizations.” Politics & Society 38(4):552–85.