Incarceration and Childhood Disadvantage

By Siobhan Montgomery O'Keefe, UC Davis

Incarceration in the United States has a serious impact on families and on children. Incarcerated adults have children at nearly the same rates as the non-incarcerated population, and children living in families with an incarcerated parent are more likely to experience certain hardships.

The adult incarceration rate in the United States was 0.86 percent in 2016, down from a high of one percent in 2008.[1,2,3]

The U.S. incarcerates more people than any other country in the world. Current incarceration rates in the U.S. are about five times higher than in the early 1970’s.

Incarceration is most common among young men, particularly black men, and men without high school diplomas.

Over half of those incarcerated in 2012 had no earnings before entering prison, and the average earnings for those who were working was $12,780 (just above the poverty threshold for a single person).

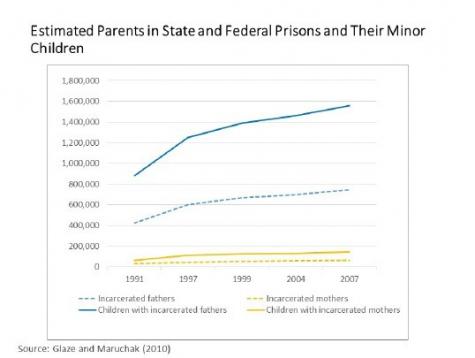

As incarceration has increased, so has the number of minor children who have an incarcerated parent.[4,5]

Incarcerated adults report having children at almost the same rate as the non-incarcerated population. In 2007 (the last year a survey was conducted), approximately 2.3 percent of children (0.9 percent of white children and 6.7 percent of black children) in the U.S. had a parent in prison.

Children who experience the incarceration of a parent tend to be socio-economically disadvantaged prior to the incarceration.[6]

Mirroring patterns for adults, children in families with incomes below the poverty line are three times more likely to experience parental incarceration. Non-white children and children whose parents did not finish high school are also at higher risk of having a parent incarcerated. Over the course of their childhood, approximately one in four black children and one in 25 white children (among a cohort born in 1990) experienced parental incarceration at some point during their childhood.

Incarceration of a parent is often a substantial shock to the child’s home and family life.[4]

35.5 percent of incarcerated fathers and 55.3 percent of incarcerated mothers in state and federal prisons reported living with their children before their incarceration. More than four in ten incarcerated mothers were single parents. About half of all incarcerated parents were previously the primary financial support for their minor children.

Paternal incarceration is associated with worse outcomes for children on average.[5]

Incarceration of a father inhibits his ability to financially contribute to the household. Families with an incarcerated parent are more likely to experience homelessness and food insecurity, and they are more likely to receive public assistance. Children of incarcerated fathers exhibit increased attention difficulties and decreased cognitive skills, which contribute to lower levels of school readiness. One exception is children whose fathers are incarcerated due to a violent offense. For these children there are no observed increases in behavioral problems.

Maternal incarceration is less common, less studied, and we know less about its effects on children.[2]

Unlike children of incarcerated fathers, children whose mothers are incarcerated usually end up living with a non-parent family member or in foster care. These children may be at increased risk of grade retention, but there is little evidence that maternal incarceration affects children’s standardized test scores.

Major surveys do not include the incarcerated or ask about former incarceration, making it difficult to understand the full extent of the impacts of incarceration.

Few surveys ask about incarcerated parents outside of smaller surveys or case studies.

References

1. Danielle Kaeble and Mary Cowhig. “Correctional Populations in the United States, 2016.” Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, 2018.

2. Jeremy Travis, Bruce Western, and Steve Redburn. “The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Causes and Consequences.” Washington, D.C., National Academies Press, 2014.

3. Adam Looney and Nicholas Turner. “Work and Opportunity Before and After Incarceration.” Washington, D.C., The Brookings Institution. 2018.

4. Lauren E. Glaze and Laura M. Maruschak. “Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children.” Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, 2010.

5. Sarah Wakefield and Christopher Wildeman. “Children of the Prison Boom: Mass Incarceration and the Future of American Inequality.” Oxford University Press, 2014.

6. Anna R. Haskins and Kristin Turney. “The Demographic Landscape and Sociological Perspectives on Parental Incarceration and Childhood Inequality.” In, When Parents Are Incarcerated: Interdisciplinary Research and Interventions to Support Children. Eds. Christopher Wildeman, Anna R. Haskins, and Julie Poehlmann-Tynan. Washington, D.C., American Psychological Association, 2018. Pages 9-28.