In Housing Crisis, Rural Californians Need Greater Legal Protections and Access to Legal Aid

By Zach Newman and Lisa R. Pruitt for the California Commission on Access to Justice (CalATJ)

California’s housing crisis stems from an inadequate supply of affordable housing coupled with insufficient legal protections for renters and homeowners. The resulting access-to-justice challenge for low-income and modest-means residents is aggravated in rural areas by the underfunding of legal-aid organizations and the state’s rural lawyer shortage. All of these factors contribute to recent increases in the state’s homeless population. Free, high-quality Legal Aid is needed urgently. We recommend the passing of new laws that protect rural low-income renters and homeowners. We also suggest that policymakers act to fund Legal Aid robustly, in a geographically equitable fashion, in order to support legal services organizations in rural areas.

Key Facts

Rural homelessness in California is rising, sometimes more quickly than its urban equivalent.

High rural eviction rates are caused in part by inadequate access to legal assistance in rural communities.

New laws protecting renters and homeowners are needed urgently, as is the provision of free, high-quality Legal Aid to low-income Californians in rural communities.

Most low-income people face at least one civil legal issue in a year.[1] For rural Californians, however, their nearest legal services provider is rarely nearby, because the vast majority of the state’s attorneys are based in metropolitan areas.[2] This leaves rural residents without access to a lawyer who can help them challenge their evictions or foreclosures, or navigate the other legal issues they face. Their meaningful participation in the justice system is thus impeded, and they may be effectively denied a legal resolution that could keep them housed. Meanwhile, although rural communities are widely assumed to be less expensive than metropolitan ones, some of California’s rural communities feature the least affordable housing in the state and nation. Consequently, many rural households face threats of eviction and foreclosure without access to the legal assistance they need.

Housing Instability and Eviction Rates

Nationally, rural households spend a quarter of their income on housing.[3] In California, some 36 percent of rural households spend upwards of 30 percent of their income in the same way. Given this fact, it is perhaps unsurprising that California’s poverty rate is the highest in the nation when housing costs and other cost-of-living metrics are taken into account. Poverty rates in California’s nonmetropolitan counties are sometimes as high as, or even higher than, those in metropolitan counties. As a result, rural homelessness is on the rise in the state, in some places on an upward trajectory sharper than that of urban homelessness.[4]

When it comes to evictions, 90 percent of landlords are represented by counsel nationally, while the figure for tenants is just 10 percent.[5] The situation in California is similarly imbalanced. On average, 160,000 renter households across California face eviction lawsuits annually. However, the eviction crisis is likely much worse than this number indicates given the fact that (1) eviction records are sealed in California and (2) many evictions proceed informally outside of the court system. Estimates suggest that around one million Californians are displaced each year, regardless of whether or not a lawsuit is filed.[6] Furthermore, the rate of evictions (as opposed to the number) can be much higher in rural areas than in urban ones. For example, Lake County experienced fewer than half as many evictions as San Francisco (255), but that rural county’s eviction rate was more than ten times as high, at 2.63 percent. The prevalence of high-eviction zones in rural places is likely caused in part by inadequate legal assistance in those communities.

Homelessness and Disaster

Rural housing challenges are often aggravated by disasters, and can contribute to the rise in individuals experiencing homelessness in rural parts of the state. California’s recent disasters have destroyed thousands of housing units and led to significant displacement and rising rents. Wildfires, for example, have hit rural areas hard, including Butte, Sonoma, Calaveras, Amador, and Shasta counties. When disasters destroy California housing, displaced families can be forced into a downward spiral. One result is an increase in homeless rural youth. The number of homeless youth rose by 20 percent statewide from 2014 to 2016, and this rise has been even steeper in rural counties, doubling in some places.

Compared with metropolitan areas, rural regions facing such increases typically have less developed infrastructure and capacity to support those facing housing instability and homelessness. In the face of such systemic disadvantages, rural Legal Aid organizations actively work to prevent low-income Californians from becoming homeless. Such organizations are integral parts of the communities they serve, protecting the interests and rights of those who need an attorney but cannot afford one. In collaboration with social services agencies, Legal Aid lawyers also provide critical services to homeless populations. But these lawyers are in short supply in rural California.

Legal Aid Invaluable but Greater Access Needed

Access to Legal Aid can have a big impact in housing matters, including eviction defense.[7] Data gathered pursuant to the 2009 Sargent Shriver Civil Counsel Act indicated that most people who need Legal Aid often experience multiple, intersecting vulnerabilities. When Shriver legal assistance was provided, it resulted in both procedural benefits and outcomes that favored long-term housing stability. In short, legal assistance generally helps people stay housed.

Nationally, three quarters of low-income people in rural places faced at least one civil legal issue in a year, while nearly a quarter dealt with six or more such issues. At the same time, the vast majority (86 percent) of issues rural people face get inadequate legal attention or, worse still, warrant no legal assistance at all. Among low-income rural residents, only 22 percent even look for legal assistance for their civil legal issues.

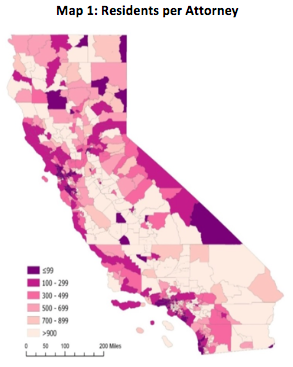

One reason for this is that too few attorneys live and work in rural places. While about a fifth of the U.S. population resides in rural areas, just two percent of small law practices exist there. In California, just over three percent of the state’s 200,000 attorneys have rural addresses. Among them, few provide free or financially accessible services. While the ratio of attorneys to residents in urban areas is 1:175, it drops to 1:626 in rural areas and 1:738 in frontier areas (see Map 1). High poverty rates in regions like the Central Valley and far northern California, where limited cell service and broadband make matters worse, amplify this lack of access.

Another problem is the uneven distribution of Legal Aid resources. Among California’s 28 rural counties, 25 were below the state average of $21.37 per poor person in expenditures on legal services. Many violations or concerns therefore do not get expert legal attention, forcing many Californians to appear without an attorney before the state’s courts. Indeed, rural residents may not know their rights or recognize the legal components of the challenges they face, thus making them less likely to consider the possibility of legal solutions.

Protect Homeowners and Renters with Statewide Housing Laws

Legal protections of renters and housing go hand-in-hand with access to Legal Aid. We suggest reforms to better protect California’s low-income and modest-means residents—with particular attention to rural areas. Statewide laws should be codified to protect rural low-income renters and homeowners. Such laws should cover rent control, just-cause evictions, and the right to counsel. While the Right to Counsel movement has yet to reach a rural jurisdiction, Governor Newsom signed into law a statewide rent cap (with just-cause protections too) that will have implications for rent prices and tenants’ rights in rural as well as urban parts of the state. This is the type of statewide law that must be put into place to bring legal protections to rural areas.

Legal Aid should be funded robustly and in a geographically equitable fashion, with rural funding increased without diminishing the urban equivalent. Relatedly, minimum-access guidelines should be created to define the baseline for funding. California needs a funding stream that ensures, on a per-capita basis, that each rural resident has access to legal services funded on par with services available to their urban counterparts. The state’s Legal Aid system should be funded with sensitivity to rural needs so that it is equipped to deliver adequate Legal Aid to all Californians, wherever they reside.

The California Commission on Access to Justice (CalATJ) is an independent nonprofit benefit corporation. Established in 1996, it explores ways to improve access to civil justice for Californians living on low and moderate incomes.

Zach Newman is a Research Attorney at the Legal Aid Association of California.

Lisa R. Pruitt is Martin Luther King Jr. Professor of Law at the UC Davis School of Law.

This policy brief is based on California’s Rural Housing Crisis: The Access to Justice Implications, published in December 2019 by CalATJ.

References

[1] The Legal Services Corporation (LSC), The Justice Gap 48 (2018), https://www.lsc.gov/sites/default/files/images/TheJusticeGap-FullReport.pdf.

[2] California Commission on Access to Justice, California’s Attorney Deserts: Access to Justice Implications of the Rural Lawyer Shortage (2019)

[3] The State of the Nation’s Housing 2018, Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University (JCHS),http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_State_of_the_Nations_Housing_2018.pdf

[4] Why California’s Rural Areas are Seeing a Surge in Homeless Youth, EdSource (June 12, 2018), https://edsource.org/2018/why-californias-rural-areas-are-seeing-a-surge-in-homeless-youth/598983. See also Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development, The 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress 2, https://www.novoco.com/sites/default/files/atoms/files/hud_2017_ahar_p1_120617.pdf.

[5] LSC Briefing to Highlight Legal Aid’s Importance to Americans Facing Eviction, LSC (Sept. 4, 2018), https://www.lsc.gov/media-center/press-releases/2018/lsc-briefing-highlight-legal-aids-importance-americans-facing.

[6] Aimee Inglis & Dean Preston, California Evictions are Fast and Frequent, Tenants Together (2018), http://www.tenantstogether.org/sites/tenantstogether.org/files/CA_Evictions_are_Fast_and_Frequent.pdf

[7] The Center for Community Solutions, Securing Stability: Legal Aid’s Lasting Impact (Executive Summary), https://www.legalaidimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Security-Stability-Executive-Summary-061019-1.pdf