Food-Bank Donors Motivated by Social Responsibility and Financial Benefits

By Alana Haynes Stein, Creighton University, and Catherine Brinkley, UC Davis

In a recent study, we explored the dependencies between community food security and local food movements. We analyzed 2.97 million pounds of food-bank donations from 296 organizations, conducted network analysis of the local food system with 77 farms and 439 market connections, and carried out interviews with food-bank donors and staff.

We found strong ties between the food bank and local food producers, particularly organic producers selling directly to the public. Even when the food was decommodified, however, producer motivations for donating were not purely based on social responsibility to feed the hungry. Rather, they also acknowledged the financial and marketing benefits of donating in terms of receiving tax credits, participating in procurement programs, and improving public relations.

Our findings suggest that policymakers focused on local food systems and food security should consider these factors and their implications for food banks.

Key Facts

- Across the U.S., more than 60,000 food assistance organizations serve over 46 million people annually.

- Food producers are motivated to donate to local food banks by a variety of factors ranging from social responsibility to tax credits and other financial benefits.

- To better address food insecurity, policymakers should focus on the right to food rather than relying on the interests of donors.

Background

Despite its rich history, the local food movement—and the transparent food networks (TFNs) that contribute to it—has often failed to address issues of hunger and inequality, disproportionately serving affluent consumers in both food and branding narratives.[1] Meanwhile, U.S. food banks have multiplied in recent years, now including a network of more than 60,000 food pantries serving more than 46 million people annually.[2] However, accessing food bank program structures can be more difficult for clients with the greatest needs.[3] The implications of these limitations are important as the government invests increasing amounts of money in food banks and as food banks are upheld by governments and the public as a solution to hunger.[4] As food banks localize responsibility for the poor, they further disadvantage the most vulnerable populations and communities which may be better served by broader programs.[5]

While food banks supplement the social welfare system, they also contribute to corporate welfare. Food waste regulations direct surplus, undesirable, and unsold food to food banks, saving corporations from landfill fees, qualifying them for charitable tax donations, and improving their image.[6] Though charitable food donations are often characterized as gifts, there are many economic incentives for donating food waste to food banks.[7]

In our study, we explored the market of charitable food. Specifically, we explored if and how the relationships between the local food movement and a rural food bank reinforced the existing globalized food system and/or fostered an alternative food movement attuned to issues of social inequality and the environment, with special attention to how economic interests motivate these relationships.

Examining food networks and food-bank donations

We focused on Yolo Food Bank, a partner distribution organization of Feeding America located in California’s Central Valley. The food bank serves Yolo County along with approximately 77 nonprofit distribution partners. Yolo Food Bank is part of Feeding America’s network of approximately 277 food banks, which comprises about three quarters of the known 371 food banks in the United States.[8] During Fiscal Year 2016-17, Yolo Food Bank distributed about 4 million pounds of food to Yolo County, California.

We used a mixed methods design that employed geospatial network analysis of Yolo Food Bank’s donation records, network data of the local, transparent food system, and in-depth interviews with two food-bank staff members and 25 people from 22 local producer donors. To identify producer donors, we analyzed Yolo Food Bank’s food donation records from the period of July 2016–June 2017, examined its 2016–2017 annual report, and interviewed members of its staff. The food bank’s local producer donors were cross-referenced with Yolo County’s TFN.[9] The Yolo County TFN had 399 total contributors (including 77 farms) with 439 markets. Our interviews focused on the formation and maintenance of relationships between Yolo Food Bank and local producer donors and provided detailed information about donors’ backgrounds and how donations fit into their organizations’ operations.

Donors motivated by both social responsibility and economic incentives

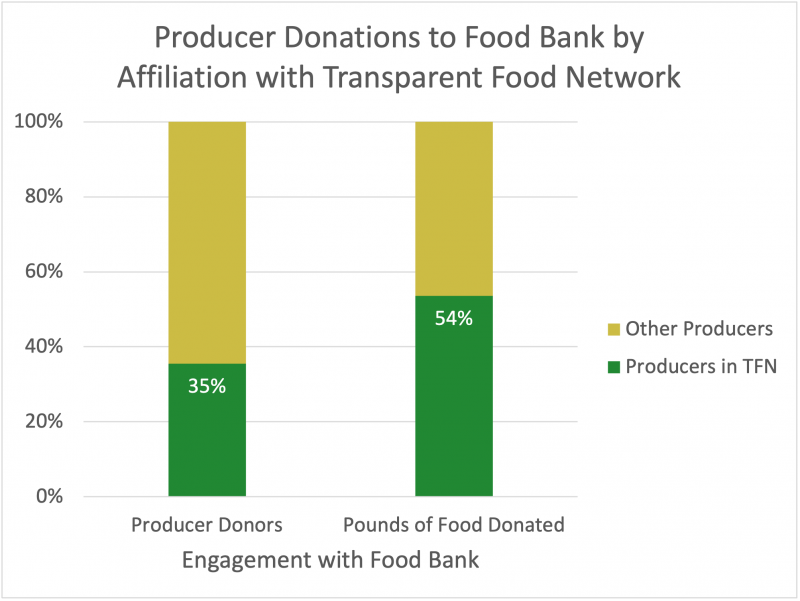

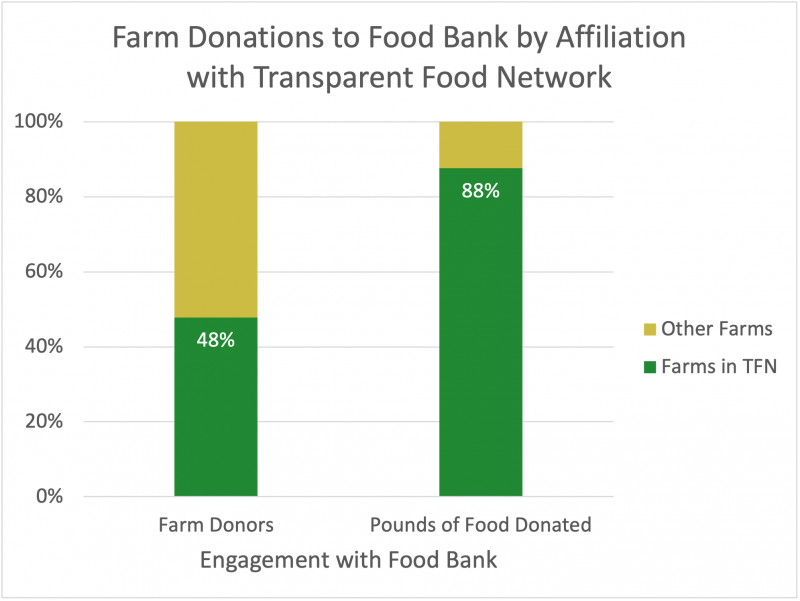

During Fiscal Year 2016-17, Yolo Food Bank received almost 3 million pounds of food donated in-kind. It received food donations from several sources, with 62 local producers contributing 552,273 pounds of food. Farms in the TFN donated the majority (54 percent) of locally produced food (296,090 pounds) that the food bank received. Yolo County TFN members comprised 22 of the 46 (48 percent) local farm donors. Farms comprised the majority of donations both in terms of number of donors (73 percent) and weight of donations (61 percent). Agricultural research companies comprised 15 percent of donors. Many well-known agricultural companies were listed as food donors on Yolo Food Bank’s annual report, including companies such as Bayer/Monsanto, Dos AgroSciences/DuPont, and HM Clause.[10] Nonprofit organizations were also important donors of locally produced food, donating a higher percent by weight (12 percent) than percent of donors (10 percent).

Most respondents (77 percent) donated food that was already being produced. A much smaller portion of donors interviewed (23 percent) grew food that was specifically intended to be donated. A third of respondents (33 percent) had also sold food to the food bank or been compensated by others for providing food to Yolo Food Bank. For small farms to donate to the food bank, cost benefits were important for making the relationship sustainable. For 75 percent of the small farms interviewed, food-bank donations, tax write-offs, and sales were able to provide a safety net amid the uncertainty of the commodified food system. One small farm both donated and sold to the food bank.

Figure 1: Percentage of all producer donors to Yolo Food Bank by their affiliation with the Transparent Food Network.

Figure 2: Percentage of farm donors (excluding nonprofit and agricultural research donors) to Yolo Food Bank by their affiliation with the Transparent Food Network.

Four donors described tax benefits as an influence on their farm donations. One small farm owner said that she donates a significant portion of her product to the food bank, sometimes all of it, because she prefers the tax write-off to the time that she would have to otherwise spend trying to market and sell her fruit. For agricultural research organizations, the costs to donate were quite low since they were already producing food and would not otherwise be able to sell their food on the market. Four of the five nonprofits interviewed did not sell any produce, and 23 percent of donors reported donating food that was grown or collected specifically to donate for people in need of food.

Many interviewed donors (90 percent) considered how their donations could reduce hunger and inequality. Most interviewed donors (65 percent) also emphasized the health and nutrition benefits of their donations. A smaller proportion (35 percent) specifically considered how their own donations addressed issues of the equitability of access to produce, local food, and/or organic food. Donors also situated their own donations of healthy food within broader contexts of societal inequality. Some small farmers recognized the contradiction of their own necessity for high prices and the inaccessibility of local, organic food for people with lower incomes.

Align producers’ interests with food-bank donations to address food insecurity

Our findings show that locally produced food can be a viable source of food for food banks, making up nearly one-fifth of the food sourced at Yolo Food Bank. However, many local food producers donated instrumentally or with market-centered objectives outside the typical charitable framework. Furthermore, the pressures on both food security and alternative food movements are growing. Our study suggests that the ‘marketness’ of ties would indicate a strong intention for the local food system to interface with the commercialized food system. An approach based on the right to food rather than reliant on the interests of donors may better address food insecurity. Stronger policy is needed to ensure that access to food is recognized as a right rather than relying on charity and the alignment of food producers’ interests with donating to food banks. Since the pandemic, declines in food bank donations across the U.S. alongside rising rates of food insecurity underscore the precarity of relying on donations to fulfill a basic human right.

Alana Haynes Stein is an assistant professor of sociology at Creighton University.

Catherine Brinkley is an associate professor of human ecology, community and regional development at UC Davis.

References

[1] Conrad, Allison. 2020. Identifying and Countering White Supremacy Culture in Food Systems. Durham, NC: Duke Sanford World Food Policy Center.

[2] Fisher, Andrew. 2017. Big Hunger: The Unholy Alliance between Corporate America and Anti-Hunger Groups. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[3] Haynes Stein, Alana. 2022. “Barriers to Access: The Unencumbered Client in Private Food Assistance.” Social Currents: 23294965221129572. https://doi.org/10.1177/23294965221129572

[4] USDA. 2022. USDA Announces Its Local Food Purchase Assistance Cooperative Agreement with California. Release No. 0163.22. United States Department of Agriculture.

[5] Strong, Samuel. 2020. “Food Banks, Actually Existing Austerity and the Localisation of Responsibility.” Geoforum 110:211–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.025

[6] Tarasuk, Valerie and Joan M. Eakin. 2005. “Food Assistance through ‘Surplus’ Food: Insights from an Ethnographic Study of Food Bank Work.” Agriculture and Human Values 22(2):177–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-004-8277-x

[7] Lohnes, Joshua. 2021. “Regulating Surplus: Charity and the Legal Geographies of Food Waste Enclosure.” Agriculture and Human Values 38(2):351–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10150-5

[8] Costanzo, Chris. 2020. “How Many Food Banks Are There?” Food Bank News. Retrieved September 16, 2020 (https://foodbanknews.org/how-many-food-banks-are-there/)

[9] Fuchs-Chesney, Jordana and Catherine Brinkley. 2020. Community Food Guide for Yolo County. Davis, CA: University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources.

[10] Yolo Food Bank. 2017. 2016-2017 Annual Report. https://yolofoodbank.org/2016-2017-annual-report/