Employment and Poverty

By Ann Huff Stevens, UC Davis

For the past two decades, U.S. anti-poverty policy has coalesced around the idea that work should be at the center of anti-poverty programs. Bi-partisan welfare reform in the 1990s focused on work requirements and time limits. The growth of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which increases after-tax income for those working at the bottom of the wage distribution, has also emphasized the importance of work. This brief summarizes facts about how many of the poor are able to work, why many cannot work, and what poverty rates are among those who work.

Of the 40.6 million Americans living in poverty in 2016, 56.1 percent were working-age adults, aged 18 to 64.[1]

Children and adults aged 65 and older also make up an important part of those in poverty (32.6 percent and 11.2 percent respectively, in 2016).[2]

Among the poor aged 18 to 64, 40.8 percent worked for some part of the year, and many of those not working reported barriers to paid work or engagement in other productive activities in 2014.

18.9 percent of the poor aged 18 to 64 did not work due to disability, 10.6 percent were in school, and 5.9 percent were unemployed and looking for work, based on tabulations from the Current Population Survey.[3]

The poverty rate among those who work for more than half of the year is much lower than for the population as a whole.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the working poverty rate was 5.6 percent, compared to a total poverty rate of 13.5 percent in 2015. This means that an estimated 8.6 million people were working poor or had income below official poverty thresholds despite working (or looking for work) for more than half the year.[4]

Among families with children, the working poverty rate is substantially higher, reflecting the higher poverty thresholds associated with larger families.

In 2015 the working poverty rate was 11.1 percent for households with children under age 18. For single-female headed families with children, the working poverty rate was 24.8 percent. (The official U.S. poverty measure takes into account a household’s pre-tax income based on household size. In 2016, a family of four earning less than $24,300 would be considered poor).[5]

Official poverty thresholds do not take into account childcare costs, which have a large impact on disposable family income.

Childcare costs can make up a substantial fraction of household expenses for low-income families. Among families who paid for any childcare, average annual childcare spending from 2012-2015 was $6,558, or 8.8 percent of total income. Among poor families who paid for childcare, spending was $2,547 and accounted for nearly 20 percent of total income.[6]

Part-time (and part-year) employment, common among the working poor, is driven by both economic and non-economic factors, including family and health needs.

In 2016 approximately 17 percent of part-time workers reported working only part-time due to economic reasons. Non-economic reasons for part-time work included caring for children or family obligations (17 percent), health or medical limitations (3 percent), and school enrollment (18 percent).[7]

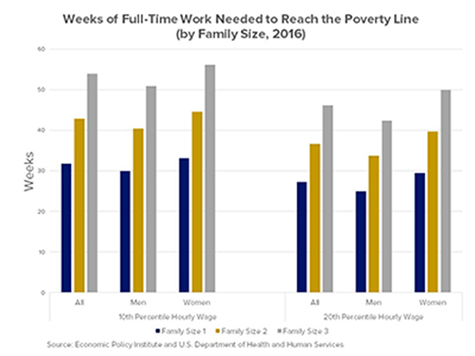

Being in low-wage jobs, working less than full-time, and working less than year-round increase the risk of poverty.

For the bottom 10 percent of wage earners, 30 weeks of full-time work per year would be needed to reach poverty line earnings for an individual. For a family of three in the bottom 10 percent, 50 or more weeks of full-time work would be required to reach the poverty line (see chart).

References

1. U.S. Census Bureau, 2017. “Demographic Makeup of the Population at Varying Degrees of Poverty: 2016.”

2. Semega, J.L. et al., 2016. “Income and Poverty in the United States”, U.S. Census Bureau.

3. Author’s calculations, Current Population Survey, 2015.

4. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017. “A Profile of the Working Poor, 2015”. Report 1068.

5. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 2016. “Computations for the 2016 Poverty Guidelines”.

6. Mattingly, M. et al., 2016. “Childcare Costs Exceed 10 Percent of Family Income for One in Four Families.” University of New Hampshire, Issues Brief 109.

7. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017. “Persons at Work 1 to 34 hours in all and in Non-Agricultural Industries by Reason for Working Less than 35 Hours and Usual Full or Part-Time Status”.