Economic and Public-Health Benefits of Easing Restrictions on Street-Food Vending

Kaniyaa Francis and Catherine Brinkley, University of California, Davis

Disparities in access to healthy food can be partially alleviated by street-food vending. California’s 2018 Safe Sidewalk Vending Act mandates that ordinances cannot regulate street food vendors for reasons beyond public health concerns. In a recent study exploring the overlooked potential of street-food vending, we reviewed municipal ordinances for 58 counties and 213 cities in California. We found that the majority are out of compliance and will need to update regulations. Eighty-five percent of the California cities we reviewed, and 75 percent of the counties, include street-food vending regulations that go beyond public health rationale and include labor laws and restrictions on time and hours of operation. Such restrictions negatively impact the health of street food vendors while also potentially jeopardizing the health of vending customers. Our study highlights the need for policy change, and suggests that broader legalization of street-food vending offers a unique opportunity to reassess the health benefits associated with it.

Key Facts

- The Safe Sidewalk Vending Act mandates that California municipalities cannot determine where street-food vendors can operate unless there is a health, safety, or welfare concern.

- 85% of the cities we reviewed, and 75% of counties, include street food-vending regulations that go beyond public health rationale and include labor laws and restrictions on time and hours of operation.

- Improving local street food-vending policy will allow vendors to operate more safely while also opening opportunities for better diet-related health.

Small-scale mobile retailers such as farmers’ markets, produce trucks and healthy street food offer locally owned, culturally relevant, cost-effective healthy food access in many parts of the world.[1,2] Nationwide, revenue for food trucks alone increased by 9.3% from 2010 to 2015, with an estimate of $1 billion in sales in 2019.[3] Passed in 2018, the Safe Sidewalk Vending Act (SB 946) mandates that California municipalities cannot determine where vendors can operate unless there is a health, safety, or welfare concern, nor can municipalities require permission from adjacent businesses to operate. Nevertheless, many cities and counties have existing code that restricts vending based on locations of operation, times of operation, and labor laws that go beyond those required in other food sectors.

The potential for positive diet-related impacts of street food have been well-documented.[4] Reasons for these positive impacts include the affordability of the produce sold, the cultural relevance of the offerings, and sales compatibility with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Electronic Benefit Transfer. Put simply, street-food vendingincreases local access to and consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, but city- and county-level permit and license requirements present significant barriers to entry. For instance, the costs of permits can sometimes be too high for vendors and their clients.[5] This can lead to unlicensed operations that lack public health oversight. Given that the consumption of street-food is common especially where unemployment is high, wages are low, job opportunities and social programs are limited, added scrutiny related to regulation also has the effect of urging an increase in policing of low-income neighborhoods.[6]

Policies to encourage healthy street-food vending present a low-cost public health intervention approach that builds upon existing vending practices in many low-income communities. In our study, we gathered municipal ordinances in California in order to explore the variation in city and county-level street food regulations, and to better understand policy barriers faced by street food vendors.[7]

Exploring Street Food-Vending Regulations in California

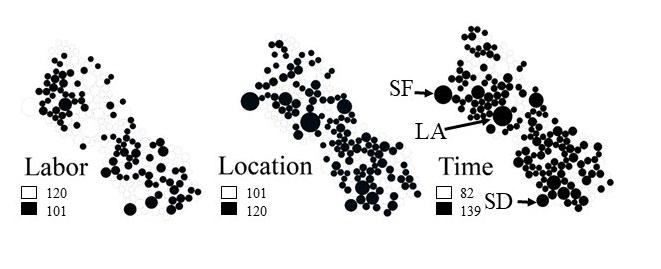

We queried the publicly available Municode library for California municipalities using the search terms: food, vendor, peddling/peddler, cart, vegetable, and fruit. In this way, we gathered street vending ordinances for 213 of the 485 California cities. Where the Municode database did not cover counties, we queried county websites for code in order to assemble a complete code database for all 58 California counties. We qualitatively coded the ordinance sections pertaining to street food based on allowance or prohibition of street-food vending, land use restrictions, labor requirements, and time restrictions (see Figure 1). We noted the date that the ordinance was passed or modified, and mapped results using ArcGIS and GeoDA.

Figure 1. Bubble map of city-level street-food vending regulation where bubble size correlates to city population, and dark shading indicates restrictions on labor, location or time. Large cities are labelled for spatial reference: San Francisco (SF), Los Angeles (LA), and San Diego (SD).

Excessive Regulations and Restrictions Go Beyond Health or Welfare Concerns

We found that the majority of cities (85 percent of those reviewed) and counties (75 percent) include street food-vending regulations that go beyond public health rationale and include labor laws and restrictions on time and hours of operation. Only 15 percent of cities we reviewed allow street-food vending without restrictions in the municipal ordinance; for counties, the figure rises to 25 percent. Most cities and counties required vendors to apply for (and display) city permits. Yet, only sixty-three cities and thirteen counties linked city permits to public health offices in their municipal ordinance, thereby calling attention to requirements for a public health official to inspect vendors’ vehicles and make sure that they followed the current health standards. Thus, restrictions for street-food vending focus less on public health and more on regulating operation time, location and vending operators.

Over 65 percent of the cities reviewed allow vending with time restrictions. The most common time limit required vendors to stop no longer than 10 minutes, a period of time too short to enable vendors to prepare and wrap food, or deliver food to a line of customers. Such restrictions effectively ban the practice of street-food vending. Another prevalent regulation is related to land-use. For example, 73 cities and 5 counties prohibited or restricted vending near schools and 36 cities and 4 counties restricted vending in public parks. However, the Safe Sidewalk Vending Act expressly prohibits local regulations from banning vending in public parks.

Labor restrictions were prevalent in cities (43 percent, 91 cities) and counties (43 percent, 25 counties). Many cities and counties had legislation in place to prohibit undocumented individuals from operating mobile food facilities. For example, sixteen cities required a Social Security number to be listed on the application, making it impossible for undocumented workers to legally operate. Such regulations were not in place for brick-and-mortar restaurant owners or workers. Fourteen cities and one county prohibited pushcarts and human-powered devices, the vending vehicle most often used by immigrant farmers. Yet, these sites allowed food trucks, demonstrating discrepancies in public health regulations along the lines of socioeconomic status.

Changing Regulations Both Necessary and Beneficial

Our results show that the majority of California’s surveyed cities and counties place restrictions on street-food vending that go beyond public health considerations and may exacerbate health disparities or produce negative health outcomes. The high cost of regulations, limited business times, restrictions on locations near highly trafficked areas, and requirements for criminal background checks and social security numbers are all impediments to the street food-vending model. In many cases, such restrictions effectively ban the practice. Such restrictions on street-food vending are common in urban areas, where street-food vending is particularly well adapted as both a means of earning a living and in serving low-income consumers. Overly restrictive street food-vending ordinances are detrimental to public health by virtue of both limiting vending opportunities and spurring the informal economy, as vendors may not seek formal permits and are more vulnerable to policing.

In order to comply with the Safe Sidewalk Vending Act, many California cities and counties will need to change their regulations. For some cities, the policy intervention may be as simple as removing a time restriction. For others, easing location restrictions would broaden the populations mobile vendors can reach and could create new economic opportunities as well as improving health. Expanding ordinances to allow pushcarts and vending from bicycles could extend the reach of healthy food options and decrease fumes, greenhouse gas emissions and noise associated with vending from vehicles. Further, county-to-county reciprocity agreements for inspections can cut costs for vendors who operate over several jurisdictions

Improving street food-vending policy will allow vendors to operate more safely while also improving diet-related health through increasing the supply of low-cost fruits and vegetables and their consumption. Policymakers would do well to review their local street food-vending ordinances in light of public health concerns for customers, vendors, and neighborhoods. The push for outdoor dining during the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that cities can quickly change food regulations for brick-and-mortar restaurants. Acting with similar urgency on reforms related to street food would help support lower-income small businesses and customers alike.

Kaniyaa Francis is an associate program manager at Public Health Advocates.

Catherine Brinkley is an Associate Professor of Human Ecology, Community and Regional Development at UC Davis.

References

[1] Yasmeen, G. (2001). Stockbrokers turned sandwich vendors: the economic crisis and small-scale food retailing in Southeast Asia. Geoforum, 32(1), 91-102.

[2] Brinkley, C., Raj, S., & Horst, M. (2017). Culturing food deserts: Recognizing the power of community-based solutions. Built Environment, 43(3), 328-342.

[3] IBIS (2020). Food Trucks Industry in the US – Market Research Report https://www.ibisworld.com/united-states/market-research-reports/food-trucks-industry/. Accessed Jan 16, 2020.

[4] AbuSabha, R., Namjoshi, D., & Klein, A. (2011). Increasing access and affordability of produce improves perceived consumption of vegetables in low-income seniors. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(10), 1549-1555.

[5] Okumus, B., & Sonmez, S. (2019). An analysis on current food regulations for and inspection challenges of street food: Case of Florida. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, 17(3), 209-223.

[6] Meneses-Reyes, R. (2018). (Un)Authorized: A study on the regulation of street vending in Latin America. Law & Policy, 40(3), 286-315.

[7] Francis, K., & Brinkley, C. (2020). Street Food Vending as a Public Health Intervention. Californian Journal of Health Promotion, 18(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.32398/cjhp.v18i1.2450