Disadvantaged Black Boys Less Likely to Be Identified for Special Education by Black Teachers

By Cassandra M.D. Hart, UC Davis, and Constance A. Lindsay, UNC Chapel Hill

In a recent study[1], we explored whether Black students benefit from being matched to a Black teacher. Specifically, we examined whether it affects the likelihood of them being identified for gifted education programs or special education services.

We found that while access to Black teachers does not affect students’ likelihood of gifted identification, Black students matched to Black teachers are less likely to be identified for special education. The results were strongest for Black boys, particularly those who were also economically disadvantaged (ED).

These findings suggest that education policymakers should consider boosting efforts to recruit more Black teachers as a means of addressing the overidentification of minoritized children for special education programs.

Key Facts

- Economically disadvantaged students of color are more likely to be identified with disabilities than other students.

- Black students are less likely to be newly identified for special education services when matched to Black teachers. However, being matched to Black teachers is not associated with changes in gifted identification.

- Recruiting more Black teachers may help reduce the overidentification of minoritized and economically disadvantaged children for special education programs.

Background

One of the most persistent problems in U.S. education policy has been inequality in educational outcomes for children from different race/ethnic groups. Black and Hispanic students have lower test scores on average than their White or Asian peers and lower rates of educational attainment, such as high school graduation and college enrollment.[2,3,4] Relative to White children, Black students are under-represented in gifted programs.[5] This is problematic because gifted program participation has been shown to be associated with better short-run and longer-run academic outcomes and because benefits to gifted identification are larger for low-income and Black and Hispanic students.[6,7] Students of color are more likely to be identified with disabilities than other students. This is also concerning, because while special education is intended to improve student outcomes, some have criticized the programs as stigmatizing students and raised concerns that over-identification of Black students for special education programs may result in services for some students who do not need or benefit from them.

At the same time, compared to White peers, Black students have lower probability of being taught by teachers of their own race/ethnicity.[8] Roughly seven percent of teachers are Black nationwide, compared to 15 percent of students.[9] This is problematic because access to Black teachers is associated with better outcomes for Black students, including performance on tests, discipline, attendance, and even high school graduation and college enrollment.[10,11]

In our study, we explored whether access to same-race teachers was associated with the likelihood that Black children entered gifted programs or special education services. We also explored whether effects of exposure to Black teachers differed by student characteristics (like socioeconomic status, sex, and student grade) as well as school characteristics (e.g., school demographic composition).

Exploring the effects of access to same-race teachers

We drew on administrative data from North Carolina elementary schools in the years 2007–08 through 2012–13. The data allowed us to observe the use of gifted and special education services and to link students to the specific teachers to whom they were assigned. We also drew some school-level variables, such as charter school status, from the National Center for Education Statistics Common Core of Data files.

Our analyses of gifted services focused on Black students in grades 2–4 (who may be identified to enter gifted programs starting in grades 3–5). Our special education analyses focused on Black students in grades 1–4 (observed entering services in grades 2–5). Our sample for disability analyses—our largest sample—included 546,433 student-year observations.

To carve out the impact of being matched to a Black teacher, we used instrumental variable techniques leveraging variation across time in the teacher composition of a given grade at a given school. We focused on the effect of current-year teachers on identification for disability or gifted services by the following year.

Being matched to a Black teacher affects special-education identification

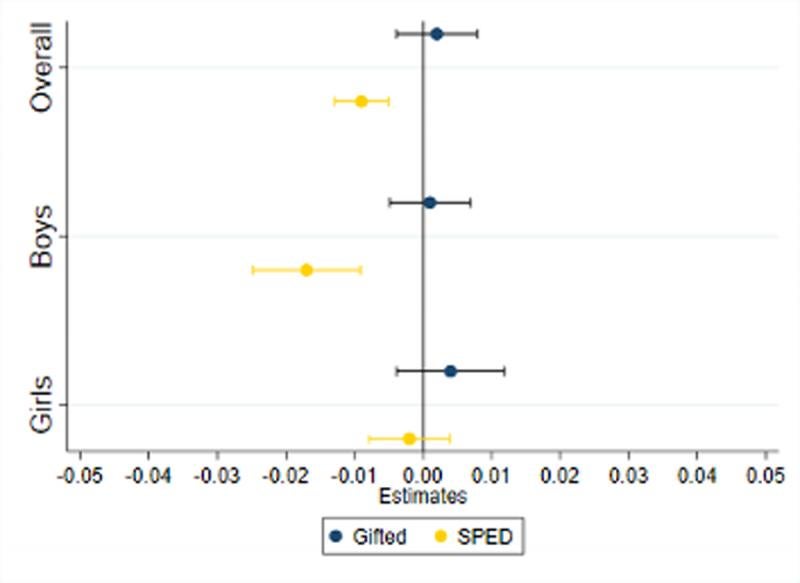

We found little evidence that being matched to a Black teacher translates into heightened likelihood of being identified for gifted services for Black students. However, there was stronger evidence that being matched to a Black teacher affects special education identification. Black students matched to Black teachers were nearly one percentage point less likely to be identified for special education services the following year. The relationship was driven primarily by boys. While the relationship between teacher race and special education identification was nonsignificant for Black girls, Black boys saw a significant reduction of about 1.7 percentage points in the likelihood of being identified with a disability if they were matched to a Black teacher.

Figure 1. Change in Probability of Identification for Gifted and Special Education (SPED) Programs if Matched to a Black Teacher, for Black Students

We found that the relationship between access to a Black teacher and disability identification was especially strong for ED Black boys. ED Black boys not previously identified with disabilities who were matched to Black teachers had roughly a two-percentage-point reduction in being newly identified with disabilities compared to their peers matched to non-Black teachers. For non-ED Black boys, Black teachers were also associated with a significant decrease in identification with disabilities, but the change was closer to one percentage point.

We observed interesting patterns based on disability type. The relationship between being matched to Black teachers and identification for disabilities among Black boys was driven by identification for “high-incidence” disabilities such as specific learning disabilities and “other health impairments”, a classification that includes attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. These high-incidence disabilities tend to have a more subjective component in their identification, meaning that teacher influence in identification may be especially strong.

Recruiting more Black teachers likely beneficial for economically disadvantaged Black boys

Though exposure to Black teachers was not related to the probability of gifted identification for Black students, on average, we found that Black students matched to Black teachers had a reduced likelihood of being newly identified with disabilities. This relationship was especially pronounced for Black boys, particularly those facing economic disadvantage. We also found that this relationship was stronger for disability categories, such as specific learning disabilities, that had a more discretionary component in their identification.

Our study points to teacher race as a potentially important contextual factor in the identification of students for special education. Policymakers and other stakeholders should consider pursuing educator diversity—specifically, recruiting more Black teachers—as one potential strategy to address overidentification of minoritized children for special education programs. Districts may also want to provide more guidance to teachers regarding when they should recommend screening for high-incidence disabilities to minimize the role of teacher discretion in the identification process.

Cassandra M.D. Hart is a professor of education policy at UC Davis.

Constance A. Lindsay is an assistant professor of education at UNC Chapel Hill.

References

1. Hart, C.M.D. & Lindsay, C.A. (2024). Teacher-Student Race Match and Identification for Discretionary Educational Placements. American Education Research Journal, 61(3): 474-507. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312241229413

2. Hanushek, E., Peterson, P., Talpey, L., & Woessmann, L. (2020). Long-run trends in the U.S. SES-achievement gap. National Bureau of Economic Research (#26764). https://doi.org/10.3386/w26764

3. National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2022, February 9). NAEP achievement gaps dashboard. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/dashboards/achievement_gaps.aspx

4. Ma, J., Pender, M., & Welch, M. (2016). Education pays 20116: The benefits of higher education for individuals and society. The College Board. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED572548.pdf

5. Office of Civil Rights. (2020a). 2017-18 State and national estimations: Gifted and talented. Office of Civil Rights Data Collection. https://ocrdata.ed.gov/estimations/2017-2018

6. Bhatt, R. (2009). The impacts of gifted and talented education. Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Research Paper Series No 09-11. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1494334

7. Card, D., & Giuliano, L. (2016). Can tracking raise the test scores of high-ability minority students? American Economic Review, 106(10), 2783–2816. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150484

8. Lindsay, C., Blom, E., & Tisley, A. (2017). Diversifying the classroom: Examining the teacher pipeline. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/features/diversifying-classroom-examining-teacher-pipeline

9. U.S. Department of Education. (2022). Percentage distribution of enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools, by race/ethnicity and state or jurisdiction. Digest of Educational Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_203.70.asp?current=yes

10. Gershenson, S., Holt, S., & Papageorge, N. (2016).Who believes in me? The effect of student-teacher demographicmatch on teacher expectations. Economics of Education Review, 52, 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.03.002

11. Lindsay, C. A., & Hart, C. M. D. (2017). Exposure to same-race teachers and student disciplinary outcomes for Black students in North Carolina. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(3), 485–510. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373717693109e