COVID-19 Recession Highlights Need for Expansion of Social Safety Net

By Marianne P. Bitler, UC Davis; Hilary W. Hoynes, UC Berkeley; and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, Northwestern University

The COVID-19 crisis has hit low-income families especially hard. Unemployment rates have risen highest for those with lower levels of education, and for Black and Hispanic individuals. In response, the Families First Coronavirus Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act have made important provisions in response. Still, many are suffering, and tremendous need remains unmet. Food insecurity rates have increased almost three times over pre-COVID rates. We attribute this to delayed payments; modest benefit levels for programs other than unemployment insurance (UI); holes in coverage; and, more structurally, a U.S. social safety net focused closely on work which does not function well when work is not available. What could be done now? Policies—including the emergency policies expanding UI and SNAP and replacing missed school meals—could be extended and adapted to the ongoing crisis. SNAP benefits could be increased by 15 percent. Another round of stimulus payments, potentially targeted at low-income families, could provide relief. Broad changes to our work-based social safety net could enable it to function more effectively in economic downturns.

Key Facts

- The recession brought about by COVID-19 has hit low-income families especially hard.

- Federal relief efforts have eased hardship, but there remains tremendous unmet need, and food insecurity is spiking.

- With some of these provisions having expired at the end of July, unmet need is likely to increase until economic conditions improve.

- A restructured safety net with automatic stabilizers could better allow for boosts during future downturns.

COVID Recession Hitting Disadvantaged Hardest

Many households and individuals are struggling financially due to COVID-19. The labor market shock, which by April 2020 saw a 14.1 percentage-point increase in the share unemployed or with a job but not at work or not in the labor force, has been significantly greater for those with lower levels of education. The increase in April unemployment was 17.8 percentage points for those with high school or less compared to 8.8 percentage points for those with a college degree or more. These striking inequalities across education groups, which continue through May and June 2020, are a recurring feature of U.S. business cycles.[1]

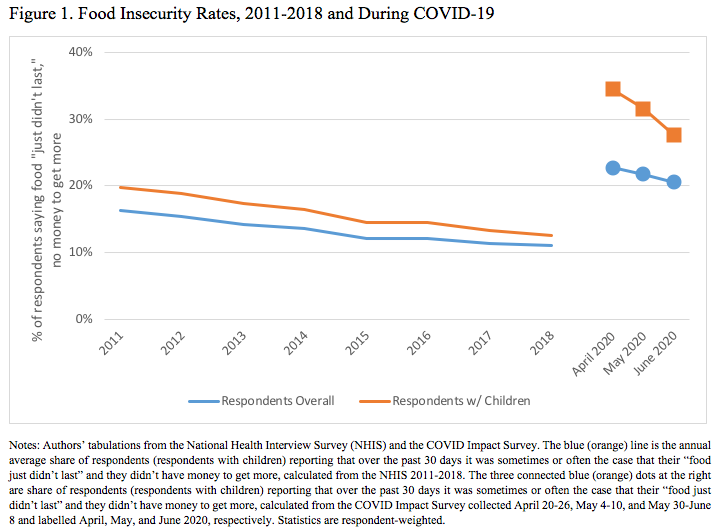

When we compared the COVID Impact Survey[2] to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), we found that rates of food insecurity increased sharply from 11 percent in 2018 (the latest available NHIS estimate) to 23 percent in April 2020. Figure 1 shows historical food insecurity rates measured as the share reporting that their food “just didn’t last and they didn’t have money to buy more” from the NHIS for respondents (blue line) and respondents with children (orange line) from 2011 through 2018. Analogous rates from the COVID Impact Survey are shown in blue circles (respondents) and orange rectangles (respondents with children). This figure shows the very large increase in food insecurity when COVID-19 hit, with a small reduction across the three COVID months. Even before the CARES Act expirations, there are clear levels of hardship.

Low-income families with children have been hit particularly hard: we saw greater elevation in food insecurity among respondents with children, from 13 percent in 2018 to 34 percent in April 2020. Reliance on food banks or similar has spiked, with weekly receipt of free food jumping to above its previous peak monthly rate.

The pandemic has also had serious repercussions for mental health. The share of adults reporting mental health problems has doubled compared with rates from 2017-18. Rates are generally higher among those with lower levels of education, and this gradient persists during COVID-19. Contributing to this distress is the fact that, in May, more than half of respondents indicated they are not “very confident” in their ability to pay for the food they need in the next four weeks, with 9 percent indicating they are “not at all confident.” These rates are uniformly higher among respondents with children and with lower levels of education.

Relief Efforts Have Eased Hardship

Between the Families First Coronavirus Act and the CARES Act, more than $1.8 trillion dollars have been allocated in relief and assistance nationally. Four elements are particularly important and represent direct payments to families: expansions to SNAP (less than $20 billion in new spending); the new Pandemic-EBT (P-EBT) program that provides payments to compensate for missed school meals; expansions to UI (almost $360 billion); and the one-time Economic Impact Payments (EIP; $216 billion).

SNAP is structured to respond quickly to increased need. Under the Emergency Allotment provision, states can award all SNAP participants the maximum benefit during state and federal health emergencies. However, to date there has been no benefit increase for the most disadvantaged SNAP recipients who were already receiving the maximum benefit pre-COVID. Relative to February, SNAP participation increased by 12 percent in April, and by 17 percent by May. By the end of July, SNAP spending has more than doubled compared to February. About 20 percent of the increase is explained by increases in participation, 40 percent is due to paying all participants the maximum benefit, and 40 percent is from P-EBT payments. Much of this increase is slated to end soon.

UI expansions have included a $600-per-week supplement (this expired at the end of July, and a smaller replacement program has only been approved for 30 states as of August 25th), a 13-week extension of fully federally funded benefits, and an expansion of eligibility for self-employed and gig-economy workers, among other patches to reach workers previously excluded. The number of UI participants has increased to record levels, with 34.5 million total continuing claims through the week ending July 4. Meanwhile, EIP provide $1,200 per adult ($2,400 for a married couple) and $500 per dependent under 17.

These relief efforts have achieved some decline in hardship. Unemployed workers who report receiving UI have lower levels of food insecurity than do those who unsuccessfully attempted to receive UI.

Food insecurity rates reported in the COVID Impact Survey dropped from 23 percent in April to 20 percent in June for respondents overall, and from 35 percent to 28 percent among respondents with children. The Census Household Pulse survey shows improvements in the share of respondents stating that they are “very confident” they will be able to afford to purchase the foods they need over the next four weeks, increasing from 55 percent of households at the beginning of May to 60 percent at the beginning of June. Nonetheless, these measures remain extremely elevated, and are generally worse for families with children, and for Black and Hispanic respondents.

Support Has Been Modest, Delayed, and Distributed Unevenly

Our research suggests three factors driving the unmet need despite relief payments. First, outside of UI, the payments made to low-income families—averaging $30-40 per week—were modest. Second, many relief payments were delayed due to difficulties states faced in implementing the $600 boost to UI, setting up new programs, and processing unprecedented numbers of claims. UI has been slow to reach the unemployed and there is a sizeable share—disproportionately those with low levels of education—who are not receiving benefits. Combining regular state UI and Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) first payments, we find that only 6.4 percent of the unemployed had received a first payment in March, rising to 53.9 percent in April and 84.9 percent in May.

Third, gaps in coverage persist. For workers in families with income below 100 percent of poverty in 2018, only 63 percent are estimated to be eligible for UI if they lose their jobs compared to 87 percent among all workers. Among those with income below poverty, 14 percent of the ineligible are unauthorized (not eligible to work legally), another 7 percent are ineligible due to being self-employed, and 17 percent are authorized and have wage and salary earnings, but do not meet the work history requirements. Thus, as many as 14 percent of those under the poverty level may still be ineligible under the best-case scenario.

Meanwhile, the design of the EIP scheme has left out the most disadvantaged Americans. Entire families that included an immigrant adult without an SSN were ineligible, meaning many citizen children and spouses (if not in the military) were excluded.Researchers estimate that 12 million non-filers are eligible for the relief payment but did not automatically receive it.[3] Some 59 percent of adults with income below poverty reported that they had received their EIP compared with 78 percent among those eligible with income above poverty. Even among those eligible, there is incomplete take-up of these programs, a direct result of the “application-based” policy environment.

Boosting the Safety Net During Recessions Could Protect the Most Vulnerable

In recent decades, the U.S. social safety net has been redesigned in ways that have made it more work-conditioned and less responsive to economic downturns. For example, neither the work-conditioned EITC nor cash welfare systematically change in response to the economy. The EITC is not designed to be countercyclical, with job-losers perhaps losing eligibility, and with payments for the previous year’s work coming in March. TANF is a block grant, and does not expand when times are bad without explicit actions by congress. Such a safety net may be adequate during times of low unemployment, but provides too little insurance against job loss and economic shocks. Thus, on the eve of the COVID-19 crisis, the U.S. safety net was providing uneven and incomplete protection. During the crisis, the increased payments authorized by Congress for UI, SNAP and for missed school meals have been crucial, if incomplete, responses. These policies have improved the responsiveness of the safety net and reduced suffering. But all are in danger of being discontinued as cases continue to surge, and tremendous unmet need persists.

If the policy responses in place at the end of July—in particular those applying to UI and SNAP—are not continued until the economic emergency recedes, unmet need may increase. If the goal is for the safety net to have a strong countercyclical stabilizing response, some features may need to be redesigned to be more tied to the business cycle. This could come, for instance, from automatic expansions to key programs during recessions.[4] The UI system could be redesigned to provide more insurance and to reach a larger share of disadvantaged unemployed worker during recessions, for example by making permanent the pandemic expansions to UI that extended coverage to self-employed and gig workers and to those with limited work histories in bad economic times. A harmonized federal and state data system could be built to facilitate making automated relief payments to all eligible Americans. These measures would increase protection for the most vulnerable individuals and families during recessions both current and future.

Marianne P. Bitler is Professor of Economics at the University of California, Davis.

Hilary W. Hoynes is Professor of Public Policy and Economics and holds the Haas Distinguished Chair in Economic Disparities at the University of California, Berkeley.

Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach is Margaret Walker Alexander Professor of Human Development and Social Policy at Northwestern University.

References

[1] Hoynes, Hilary; Doug Miller; and Jessamyn Schaller, 2012. “Who Suffers During Recessions?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 26, Number 3, pages 27–48. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.26.3.27

[2] Wozniak, Abigail; Joe Willey; Jennifer Benz; and Nick Hart. COVID Impact Survey: Version 1 [dataset]. Chicago, IL: National Opinion Research Center, 2020

[3] Marr, Chuck; Kris Cox; Kathleen Bryant; Stacy Dean; Roxy Caines; and Arloc Sherman. 2020. “Aggressive State Outreach Can Help Reach the 12 Million Non-Filers Eligible for Stimulus Payments,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep24767.pdf

[4] Boushey, Heather; Ryan Nunn; and Jay Shambaugh. 2019. “Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy.” Hamilton Project and Washington Center for Equitable Growth. https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/OnePager_Stabilizers_FINAL_04252019.pdf