Among Disadvantaged Children, Education is Largely Unaffected by Divorce

By Jennie E. Brand, University of California, Los Angeles; Ravaris Moore, Loyola Marymount University; Xi Song, University of Pennsylvania; Yu Xie, Princeton University

Parental divorce is generally associated with unfavorable outcomes for children, particularly with regard to education. But not every divorce is equally harmful for the children it affects. Why is this? In a recent study, we found that parental divorce does lower educational attainment, but only for children whose parents are statistically unlikely to separate. For these children, divorce is an unexpected shock to an otherwise privileged childhood. However, among children whose parents are, for socioeconomic and family reasons, more likely to divorce, we found no impact of divorce on their education. Indeed, disadvantaged children of high-risk marriages may actually benefit from the removal of marital discord from the home. In light of these findings, policies that promote marital stability among disadvantaged families may be less effective than policies that address the root causes of associated socioeconomic disadvantage.

Key Facts

- Children’s responses to divorce vary by socioeconomic characteristics and family wellbeing.

- Divorce is less disruptive to educational attainment for disadvantaged and minority children, whose parents are more likely to divorce.

- Policy should attend to socioeconomic and family conditions in which adverse events such as divorce become expected.

Parental divorce is, on average, associated with unfavorable outcomes among children, including their ability to complete high school and to attend and complete college.[1,2] But families differ in their expectation of, and ability to adjust and respond to, marital disruption. Families expecting marital stability may experience considerable adjustment difficulties when divorce occurs, leading to worse outcomes for children. By contrast, divorce among families who have come to expect disadvantage and instability may not incur the same negative consequences. Nonetheless, policymakers continue to promote marital stability among disadvantaged and minority families. For example, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (TANF) lists “the formation and maintenance of two-parent families” as one of its goals, while the Healthy Marriage and Responsible Fatherhood initiative (HMRF) seeks to “secure households and communities for the well-being and long-term success of children and families.”[3,4]

The focus on family stability, especially among disadvantaged families, is misguided. Children’s response to parental divorce varies by socioeconomic characteristics and family wellbeing. While children of more advantaged parents and white children experience considerable negative effects of parental divorce, children of married parents with high levels of conflict are no better off, and in fact may fare worse in some respects, than children of single parents.[5,6]

On average, white children and children of more advantaged parents are less accustomed to negative disruptive events and underprivileged circumstances than racial and ethnic minority children and children of less advantaged parents.[7] More advantaged children thus experience greater negative effects of a parental divorce than children growing up in less favorable socioeconomic circumstances. In our study[8], we sought to investigate how these greater or lesser negative effects play out with regard to educational attainment.

Measuring Likelihood and Effect of Divorce

To study the differential impact of parental divorce, we used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), which is a nationally representative sample of 12,686 respondents who were 14 to 22 years old when first surveyed in 1979 conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. These individuals were interviewed annually through 1994 and biennially thereafter. In 1986, the National Longitudinal Survey began a separate survey of the children of NLSY women, the NLSCM. Data have been collected every two years since 1986.

We linked data on women from the NLSY with data on children from the NLSCM (n = 11,512 children and n = 4,931 mothers). We constructed measures of whether and when a child under the age of 18 experienced a parental divorce. We restricted our sample to 8,319 children who were born to 3,940 married mothers. This restriction focused on a relatively homogenous population of children who were all at risk for a parental divorce from the time of birth. We further restricted the sample to those who were at least 18 years old by 2012 (n = 7,258 children). Over a third of the sample (n = 2,420 children) experienced a parental divorce over the course of childhood.

We include an extensive set of variables to predict the likelihood of divorce, including parental family background, socioeconomic status, cognitive and psychosocial skills, and family formation and wellbeing, and use these factors to compare children whose parents had a similar likelihood of divorce. Our measures of children’s educational attainment included high-school completion by age 18, college attendance by age 19, and college completion by age 23.

Disruption Less Severe When Divorce More Likely

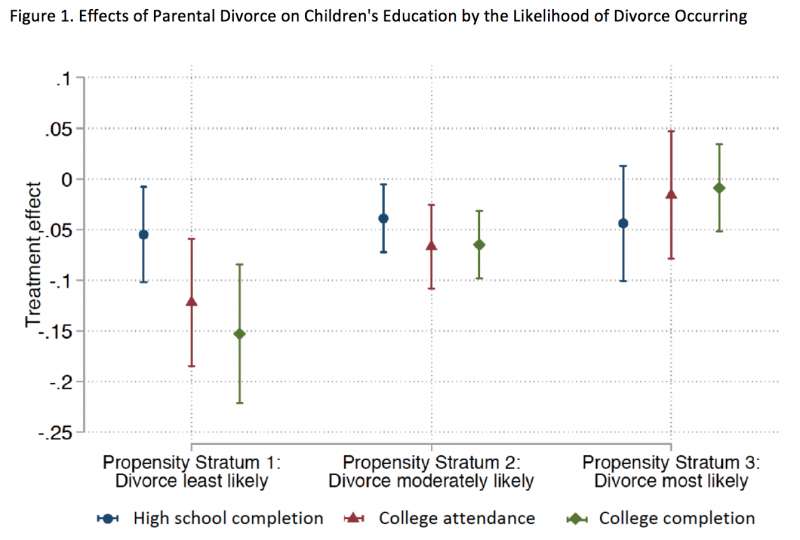

As shown in Figure 1, we found a significant negative effect of parental divorce on educational attainment, particularly college attendance and completion, among children whose parents were unlikely to divorce. Families expecting marital stability, unprepared for disruption, may experience considerable adjustment difficulties when divorce occurs, leading to negative outcomes for children. By contrast, we found no effect of parental divorce among children whose parents were likely to divorce.

Taking the sample as a whole, we found that divorce was associated with an 8 percent lower probability of children’s high school completion, a 12 percent lower probability of college attendance, and an 11 percent lower probability of college completion. Among children with a low propensity for parental divorce, we found a 6 percent lower level of high school completion, a 12 percent lower level of college attendance, and a 15 percent lower level of college completion. Among children with a moderate propensity of parental divorce, we observed a 4 percent lower level of high school completion, and a 7 percent lower level of college attendance and completion. We found no significant effect of parental divorce among children with a high propensity for parental divorce.

Divorce a Symptom of Educational Disadvantage, Not a Cause

The degree of disruption caused by divorce varies by the likelihood and corresponding expectation that events such as divorce will occur. Children of high-risk marriages, who face many social disadvantages in childhood irrespective of parental marital status, may anticipate or otherwise accommodate to the dissolution of their parents’ marriage. In other words, parental divorce may not furtherimpede the educational attainment of children who have grown accustomed to adverse events in their lives via high levels of socioeconomic instability and family conflict.

This is telling. Clearly, given that the likelihood of family instability generally declines with socioeconomic status and family wellbeing, a simple distinction between children with divorced and nondivorced parents oversimplifies how parental marital status impacts children’s educational attainment. Indeed, we found that educational outcomes differ far more by the propensity to divorcethan by parental divorce status.

While the effect of divorce is seemingly greatest among more advantaged children who may not anticipate disruption, we should not shift attention away from children who expect disadvantage. On the contrary, rather than promoting marital stability among disadvantaged families, social policy should address the underlying causes of family instability, such as socioeconomic and family conditions, which depress children’s educational attainment to the point that parental divorce has no additional effect.

Jennie E. Brand is Professor of Sociology and Statistics at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Ravaris Moore is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Loyola Marymount University.

Xi Song is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Yu Xie is Bert G. Kerstetter ’66 University Professor of Sociology at Princeton University.

This policy brief was supported by funding from the UC Office of the President Multicampus Research Programs and Initiatives, Grant MRI-19-601054.

References

[1] McLanahan S, Tach L, Schneider D (2013) The causal effects of father absence. Annu Rev Sociol 39:399–427.

[2] Bernardi F, Boertien D (2016) Understanding heterogeneity in the effects of parental separation on educational attainment in Britain: Do children from lower educational backgrounds have less to lose? Eur Sociol Rev 32:807–819.

[3] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2002) State Policies to Promote Marriage. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/state-policies-promote-marriage

[4] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2015) Healthy Marriage and Responsible Fatherhood. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/healthy-marriage

[5] Bernardi F, Radl J (2014) Parental separation, social origin, and educational attainment: The long-term consequences of divorce for children. Demogr Res 30:1653–1680.

[6] Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A (2003) Life with (or without) father: The benefits of living with two biological parents depend on the father’s antisocial behavior. Child Dev 74:109–126.

[7] Amato PR (2001) Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. J Fam Psychol 15:355–370.

[8] Brand et al (2019) Parental divorce is not uniformly disruptive to children’s educational attainment. PNAS 116(15): 7266-7271.