Affirmative Action in Local Elections Associated With Improved Children’s Health

By Priyanka Pandey, UC Davis; K G Sahadevan, Indian Institute of Management Lucknow; and Paul D. Hastings, UC Davis

Structural and social inequalities are determinants of poor human development outcomes in low-and middle-income countries. In a recent study of a historically marginalized group in India, we examined the effects of affirmative action in local elections on children’s health and education.

We found that village clusters with a mandate for affirmative action in the 2021 local elections showed better health outcomes in the years following the elections than did villages clusters without. Specifically, mandated clusters had lower infant mortality rates (IMR) and higher odds of two prenatal visits, two tetanus vaccinations, and prenatal supplement received by the second trimester. Mandated clusters did not, however, see improved test scores, and leaders elected in part via affirmative action reported more discrimination and more difficulty in working with teachers relative to health workers. Overall, affirmative action in local governments in India predicted greater infant survival and improved prenatal health services.

In the context of poverty and inequality in the U.S., these findings suggest that addressing structural inequities at the local level can help to improve health outcomes among children from disadvantaged households.

Key Facts

- In local government elections in India, states must reserve a fraction of seats for historically disadvantaged groups such as Scheduled Caste.

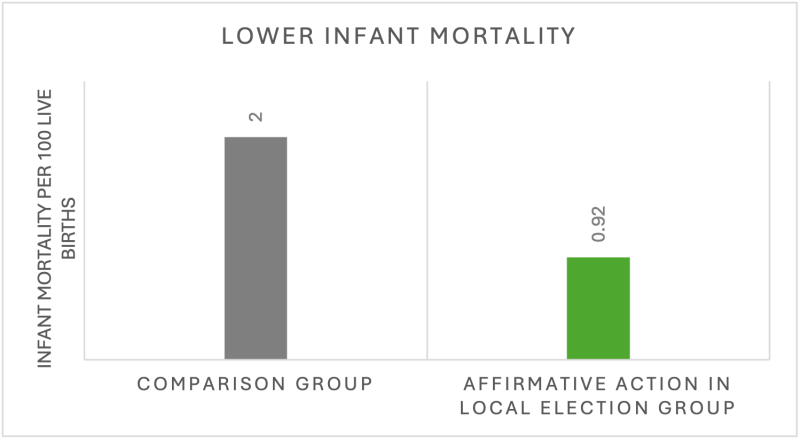

- Infant mortality rate was 54 percent lower in village clusters with affirmative action than in those without in the high-poverty state of Uttar Pradesh.

- Addressing structural inequities at the local level can help improve health outcomes.

Background

India accounts for 26 percent of infant deaths in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) globally, or 0.59 million annually. Eighty-five percent of these deaths are deemed preventable. Though on average children in India complete 11 years of schooling by the age of 18, their learning is equivalent to just seven years. Children in India can expect to be only 49 percent as productive in adulthood as they could be if they enjoyed full health and complete education.[1]

Structural and social inequalities of caste, endemic poverty, and a 26-percent illiteracy rate weaken individual and collective agency to ensure quality services.[2] Marginalized and minoritized groups such as scheduled caste (SC), historically at the bottom of India’s caste and social hierarchy, have poorer outcomes due to discrimination and lower socioeconomic status.[3] SC lag in multiple outcomes of human development such as education, health, and income. Compared to others in India, they depend more on public services, particularly in rural areas, where 69 percent of the Indian population live, with greater illiteracy and poverty.[4]

Indian states are divided into districts, blocks and village clusters for administrative purposes. A village cluster directly elects a local head and council members every five years. In 1993, through efforts to decentralize governance, India established a policy rule mandating states to reserve a fraction of seats in local government leadership for historically disadvantaged groups such as SC.[5] The policy rule assigns ‘SC reservation’ in local leader seats to village clusters based on their SC population.

In our study,[6] we examined the association of affirmative action for SC in local government with local health and public school outcomes in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh is India’s most populous state, with a population comparable in size to that of Brazil. It is also among the four poorest states in India, with 23 percent of its population being multidimensional poor.[7]

Examining the effects of affirmative action

Our study covered 120 village clusters across ten blocks. Local elections involving affirmative action for SC took place in May 2021. Recruitment of participants and primary data collection took place from October to December 2023. We collected administrative data from April 1st until October 31st, 2023.

In each sample village cluster, we obtained data from local health records on total births and infant deaths. In unannounced visits to local public schools, we tested students on basic competencies in language and mathematics. We also recorded teacher presence and activity to measure teacher engagement in school, as well as student and teacher gender and caste. To aid in interpretation of the findings, we collected qualitative data in local leader interviews on leader governance, experiences of domination and discrimination, and perceived stress.

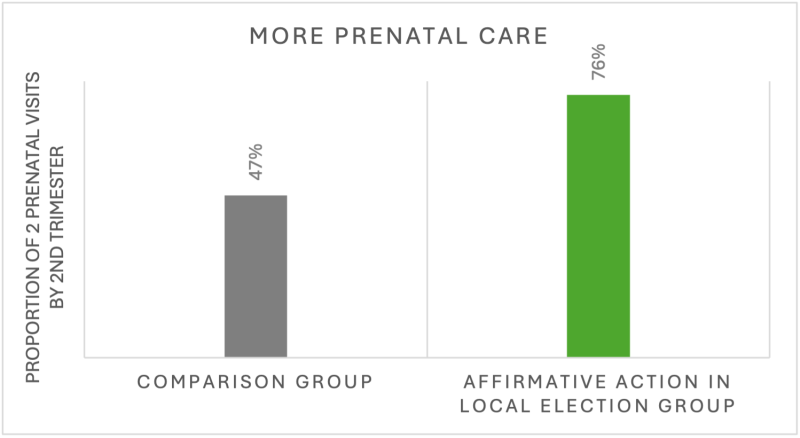

Affirmative action associated with lower infant mortality

In village clusters with affirmative action, infant mortality rate was 54 percent lower than in those without (Figure 1). Pregnant women in clusters with SC reservation were about eight times more likely to have at least two prenatal checkups. They were also about five times more likely to get two tetanus shots during pregnancy, and about four times more likely to receive a prenatal supplement by the second trimester (Figure 2). Test scores, however, were not improved by affirmative action, and teacher engagement at school (present and teaching) was lower in clusters with SC reservation. Compared to leaders in clusters without SC reservation, leaders in village clusters with affirmative action reported experiencing more discrimination and had more difficulty working with teachers than with local health facilitators.

Figure 1: Lower infant mortality rates in village clusters with reserved elected seats for Scheduled Caste 2.5 years after the 2021 elections, versus adjacent village clusters.

Figure 2: Higher proportions of pregnant women having 2 prenatal clinic visits by second trimester in village clusters with elected seats reserved for Scheduled Caste 2.5 years after the 2021 elections, versus adjacent village clusters.

Address structural inequities to improve children’s health

Our findings indicate that addressing structural inequities by allocating authority to historically marginalized groups in local governments may confer health benefits to expectant mothers and infants. Our study provides evidence of local affirmative action’s associations with health outcomes in an LMIC context. This replicates patterns observed in high-income countries like the US. Indeed, studies in the US indicate that after the implementation of other forms of affirmative action, all mortality and IMRs declined for structurally and socially disadvantaged and minoritized groups, such as African Americans.[8]

Though our study focused on the Uttar Pradesh region of India, our findings have clear implications for U.S. policy. Firstly, electoral affirmative action can improve health outcomes such as infant mortality—a key indicator of population health8—and maternal care. Secondly, local-level efforts to address structural inequities are likely to help to improve health outcomes among socioeconomically disadvantaged children.

Priyanka Pandey is a PhD student in human development at UC Davis.

K G Sahadevan is a professor of economics at the Indian Institute of Management Lucknow.

Paul D. Hastings is a professor of psychology at UC Davis.

References

1. World Bank, Human Capital Country Brief, India (2023). https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/64e578cbeaa522631f08f0cafba8960e-0140062023/related/HCI-AM23-IND.pdf. Accessed 15 October 2024.

2. NITI Aayog, National multidimensional poverty index: Baseline report (Government of India, India, 2021). https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2021-11/National_MPI_India-11242021.pdf. Accessed 12 October 2024.

3. V. Patel, K. Mazumdar-Shaw, G. Kang, P. Das, T. Khanna, Reimagining India’s health system: A Lancet Citizens’ Commission. Lancet 397, 1427–1430 (2021), DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32174-7

4. NITI Aayog, Social inclusion (Development Monitoring and Evaluation Office (DMEO), Government of India, 2022). https://dmeo.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-10/Thematic-report_Social-Inclusion_14102022-%20Final.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2024.

5. Ministry of Panchayati Raj (Local Governance), 73rd constitutional amendment act (Government of India, 1992). https://panchayat.gov.in/document/73rd-constitutional-amendment-act-1992/.

6. P. Pandey, K G Sahadevan, P.D. Hastings. Association of affirmative action with health and education outcomes and services in India. PNAS 122, 41 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2502290122

7. NITI Aayog, India—National Multidimensional Poverty Index: A Progress Review (Government of India, India, 2023).

https://ophi.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-03/India_National_MPI_2023.pdf. Accessed 15 October 2024.

8. N. Krieger, Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: An ecosocial approach. Am. J. Public Health 102, 936–944 (2012), DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544.