Administrative Burden Causes Cyclicality and Inconsistency in WIC Benefit Redemptions

By Marianne Bitler, UC Davis; Jason Cook, University of Utah; Seojung Oh, UC Davis; and Paige Rowberry, University of Utah

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) provides EBT benefits redeemable for healthful foods for low-income, nutritionally at-risk pregnant/postpartum women and young children. In a recent study, we found evidence of a new form of benefit redemption cycle in WIC, different from that seen with Food Stamps.

We found that WIC redemptions peaked at both the beginning and the end of the month. Beginning-of-the-month excess redemptions were concentrated among more fully redeemed items such as infant formula, while end-of-the-month excess redemptions were concentrated among less fully redeemed items such as infant meats. We also found that many WIC beneficiaries went at least one month without redeeming anything. This cyclicality and inconsistency were likely due in part to administrative burden, which policymakers should seek to reduce.

Key Facts

- WIC provides access to healthful foods to low-income, nutritionally at-risk pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding women, infants, and children under five years old.

- Administrative burden likely contributes to cyclicality in WIC redemptions; this cyclicality may mean inconsistent use among recipients.

- Reducing administrative burden in WIC may enable recipients to redeem benefits more consistently.

Background

WIC provides low-income, nutritionally at-risk pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding women, infants, and children under five years old access to foods that are high in nutritional value. In fiscal year 2019, 6.4 million individuals participated in WIC, with total federal food spending reaching $3.1 billion. There is established evidence of cyclicality in the redemption of public assistance benefits, where benefits are used much more intensely right after disbursement. In addition to being largely for specific food items and redeemable only at certain vendors, WIC benefits are only available for distinct one-month periods. Together, these factors mean that, on average, not all items in the WIC food package are redeemed.

A WIC benefit cycle may affect downstream outcomes, as has been shown for other safety-net programs. For example, in the case of SNAP, the monthly benefit cycle leads to excess expenditures and calorie consumption at the start of the benefit disbursal month, [1,2,3] negatively affecting other outcomes such as health outcomes, crime, test scores, and school suspensions.[4] The presence of WIC redemption cycles could be due in part to the administrative burden on recipients. Administrative burden has been defined as “the costs associated with applying for, receiving, and participating in government benefits and services,” something that “can be a significant obstacle to individuals accessing support to which they are entitled.”[5] For instance, if redeeming WIC necessitates visiting a special store, then beneficiaries may be more likely to lump redemptions into a single trip to reduce travel costs. In our study[6], we leveraged rich administrative data on WIC redemptions in Nevada to explore the WIC cycle, its connection to administrative burden, and consider its implications.

Exploring WIC redemptions

Our data included redeemed benefits in WIC from July 2018 through December 2020 for Nevada. Our data provided extensive details on WIC redemptions, including the redemption date, benefit category, and quantity of items redeemed, as well as the UPC where available. In addition, we had basic information on household characteristics such as household size. We started with 13,637,170 UPC-level redemption instances and dropped a small share of observations with missing redemption dates (38) or duplicated records (7,779). We also used state-aggregated data on the share of items redeemed by month, sorting our food categories according to which foods had the highest redemption rate in July 2019. We explored the cyclicality of WIC through a series of graphical analyses and regressions.

WIC redemptions are inconsistent and cyclical

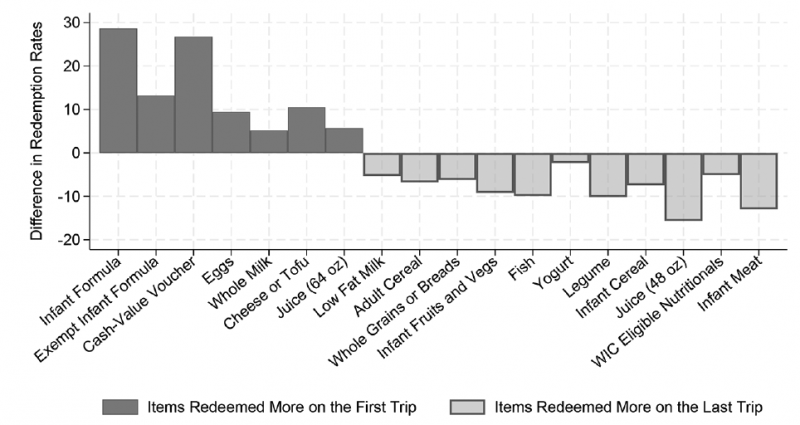

Redemptions overall were 4 percentage points higher on the first of the month relative to the middle of the month (see Figure 1). We found that some goods, if redeemed at all, were generally redeemed right away. These included infant formula, infant cereal, the cash-value voucher for fruits and vegetables, and infant fruits and vegetables. In the case of infant formula and the cash-value vouchers, this difference was more than 20 percentage points. Cheese, and eggs were also popular, while 64-oz containers of juice and whole milk were all redeemed more often on the first trip than the last one. The least popular items, or those that were hardest to find, are oddly sized juice, infant meats, legumes, fish, and infant fruits and vegetables. Cereals and whole-grain bread were also less likely to be fully redeemed.

Figure 1. Difference in redemption rates between the first and last trip in a month.

There was also an increase in redemptions at the end of the month for almost all the categories but infant formula. Goods that were primarily redeemed at the end of the month included fish, yogurt, adult cereal, an unusual juice size (48 oz), infant meats, and legumes. Every item had at least some excess redemptions on the final day of the month. This was consistent with WIC recipients redeeming the remainder of their package to avoid losing benefits that expire at the end of the month. Strikingly, the excess redemptions were much higher at the end of the benefit month than at any other point in the month for those items that were infrequently redeemed.

Roughly 50 percent of households in our sample made one or two trips a month. In addition, we found gaps in some WIC participants’ redemption patterns. Some 37 percent of households appeared in our data with redemptions for at least two months but exhibited at least one month where they did not redeem anything. Households were more likely to buy a good on their last trip.

Reducing administrative burden may enable expanded WIC redemptions

We found that WIC recipients did not redeem benefits smoothly within the benefit month. Instead, they redeemed some food items more at the beginning of the month and others more at the end. This evidence is inconsistent with the permanent income hypothesis, which presumes that the timing of anticipated income should not affect spending as long as households can smooth consumption across periods. We also found clear evidence that not all the goods were equally desired. Some items were popular, including infant formula and the cash-value voucher. Others were used up at the end of the month but not much otherwise. These included some of the least-redeemed items such as infant meats.

A large share of households had gaps in their redemptions, with 37 percent of those redeeming WIC in at least two months experiencing at least one month with no redemptions. Our finding that a substantial share of recipients had month-long gaps in their redemption patterns suggests that administrative burdens may be preventing consistent use. Further, the cyclicality that we observed both at the beginning and at the end of each month is consistent with WIC recipients being liquidity-constrained; that is, if they have insufficient disposable income to meet their needs. To ease the strain placed by this cyclicality on disadvantaged families, policymakers could seek to minimize administrative burden that may prevent WIC recipients from redeeming their benefits consistently.

Marianne Bitler is a professor of economics at UC Davis.

Jason Cook is an assistant professor of quantitative analysis of markets and organizations at the University of Utah.

Seojung Oh is a PhD candidate in the Department of Economics at UC Davis.

Paige Rowberry is a PhD candidate in the Department of Finance at the University of Utah.

References

[1] Wilde, P., and C. Ranney, 2000. “The Monthly Food Stamp Cycle: Shopping Frequency and Food Intake Decisions in an Endogenous Switching Regression Framework.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 82 (1), 200–213.

[2] Shapiro, J., 2005. “Is There a Daily Discount Rate? Evidence from the Food Stamp Nutrition Cycle.” Journal of Public Economics 89 (2–3), 303–325.

[3] Todd, J. E., 2016. “Revisiting the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Cycle of Food Intake: Investigating Heterogeneity, Diet Quality, and a Large Boost in Benefit Amounts.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 37 (3), 437–458.

[4] Seligman, H., A. Bolger, D. Guzman, A. Lopez, and K. Bibbins-Domingo, 2014. “Exhaustion of Food Budgets at Month’s End and Hospital Admissions for Hypoglycemia.” Health Affairs 33 (1), 116–123.

[5] Office of Management and Budget, 2022. “Strategies for Reducing Administrative Burden in Public Benefit and Service Programs.” Technical report, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Washington, DC.

[6] Bitler M, Cook J, Oh S, Rowberry P., 2025. New Evidence on the Cycle in the Women, Infants, and Children Program: What Happens When Benefits Expire. National Tax Journal. 77 (1):175-197. doi: 10.1086/728678