Access to Food Stamps Improves Children’s Health and Reduces Medical Spending

By Chloe N. East, University of Colorado Denver

The Food Stamp Program (FSP, known since 2008 as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP) is one of the largest safety-net programs in the United States. It is especially important for families with children. However, the FSP eligibility of documented immigrants has shifted on multiple occasions in recent decades. When I studied the health outcomes of children in documented immigrant families affected by such shifts between 1996 and 2003, I found that just one extra year of parental eligibility before age 5 improves health outcomes at ages 6-16. This suggests that expanding food-stamp access for such families has lasting long-run benefits for their children and may help to reduce public medical expenditures in the medium term.

Key Facts

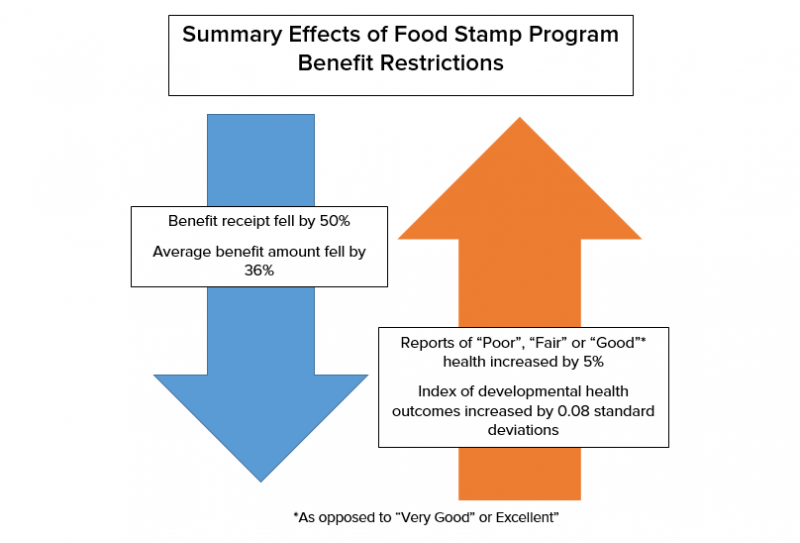

- Immigrants’ loss of eligibility reduced participation in the Food Stamp Program among U.S.-born children of immigrants by 50%, and reduced the average benefits they received by 36%.

- Loss of parental food-stamp eligibility before age five has clear negative effects on developmental health outcomes and on parental reports of the child’s health in the medium-run.

- An additional year of food-stamp access in early life reduces medical expenditures in the medium-run by roughly $140 per child.

In 2011, 25 percent of all children in the U.S. and nearly 15 percent of the total population received benefits from the FSP.[1] Measured as their cash equivalent, FSP benefits reduced the poverty rate among participants by 16 percent that year.[2] For policymakers and economists, the program’s positive contributions to family nutrition and well-being must be squared with its direct costs. Concerns over increased spending resulted in several cuts to food-stamp generosity in the past several years[3], with potentially larger cuts on the horizon—especially for immigrants.[4,5]

Before 1996, children of immigrants made up 20 percent of all children receiving food stamps and 30 percent of all children in poverty. But the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996 made many documented immigrants ineligible for food stamps. Between 1998 and 2003, some had eligibility restored to them. Nonetheless, welfare reform caused immigrants’ participation in the FSP to decline significantly.[6] In this study, I examined the extent to which the children of immigrants were affected by these food-stamp eligibility changes, in terms of their access to FSP benefits and their overall health.

Examining Health Outcomes

To measure medium-run health outcomes over this period, I used the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) from 1998 to 2015. I focused on children of immigrants, born in the U.S. between 1989 and 2005—U.S. citizens, therefore—and observed at ages 6-16. This age range begins after early-life changes in FSP eligibility and ends before children might choose to leave home. To measure overall health status, I used parent-reported child health, overnight hospitalizations, number of school days missed, and number of doctor visits. I also examined outcomes related to developmental conditions and mental health. Together, these measures enabled me to develop a clear picture of the health of children whose food-stamp eligibility changed after PRWORA passed in 1996.

Calculating Costs and Benefits

Changes in parental eligibility brought about by PRWORA led to large changes in program receipt among U.S.-born children of immigrants. Loss of parental eligibility reduced participation by 50 percent, and reduced the average benefits received by 36 percent. Among children whose mothers have a high-school education or less, an additional year of parental food-stamp eligibility in early life improved health in the medium-run. There were statistically significant improvements in parent-reported health measures and a decrease in negative developmental health outcomes, such as autism, learning disabilities, ADHD, or developmental delays.

To get a sense of the significance of these health gains, I considered the average annual health care costs for children with differing health reports. A child who is reported to be in “Poor”, “Fair”, or “Good” health has average annual health care costs of $2450. For a child in “Excellent” or “Very Good” health, that cost goes down to $1462. Using these cost differences, I take present discounted values and calculate the effects of program eligibility. I estimate an additional year of parental FSP eligibility in early life leads to about $140 in benefits, roughly 42 percent of the program’s direct costs. There may be other benefits from and costs of the program, but this does suggest that net costs of the program may be substantially below direct outlays. This reduction in medical costs may benefit families directly. It may also represent government savings as these children go on to participate in Medicaid and SCHIP.

Expanding Access to Food Stamps Would Have Lasting Positive Effects

After PRWORA made immigrants ineligible to receive Food Stamps in 1996, the number of U.S.-born children of immigrants benefiting from the program was cut in half. My study shows that for a child under the age of five, loss of parental eligibility has clear negative effects on the child’s health in the medium-run.

These findings confirm that changes in nutrition and resources in the first few years of life can have lasting effects on children’s health. They also suggest that access to the Food Stamp Program in early life can significantly reduce medical expenses, both for families and for government institutions.

Chloe N. East is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Colorado Denver and a Research Affiliate at IZA – Institute for the Study of Labor. Dr. East received her PhD in Economics from the University of California, Davis, in 2016.

References

[1] Moffitt, Robert A. 2013. “The Great Recession and the Social Safety Net.” Russell Sage Foundation and the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality.

[2] Food Research and Action Center. 2012. “The SNAP Effect: Lifting Households Out of Poverty.”

[3] Dean, Stacy, and Dottie Rosenbaum. 2013. “SNAP Benefits Will Be Cut for Nearly All Participants in November 2013.” The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities.

[4] Dewey, Caitlin, and Tracy Jan. 2017. “Trump’s Plans to Cut Food Stamps Could Hit His Supporters Hardest.” Washington Post.

[5] Parrott, Sharon, Shelby Gonzales, and Liz Schott. 2018. “Trump “Public Charge” Rule Would Prove Particularly Harsh for Pregnant Women and Children.” The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[6] Haider, Steven J, Robert F Schoeni, Yuhua Bao, and Caroline Danielson. 2004. “Immigrants, Welfare Reform, and the Economy.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 23(4): 745-764.