ACA Policies Aimed at Adults Also Help Low-Income Families with Children

By Lauren E. Wisk, UC Los Angeles; Alon Peltz and Alison A. Galbraith, Harvard Medical School

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) sought to improve access and affordability of health insurance. Most ACA policies targeted childless adults; the extent to which these policies also positively impacted families with children has been unclear. In a recent study, we aimed to examine changes in health care-related financial burden for US families with children before and after the ACA, based on income-eligibility for ACA policies. Using a difference-in-differences design in a cohort of U.S. families with children, we found that, following the ACA, low- and middle-income families with children who were eligible for key ACA policies experienced greater reduction in out-of-pocket costs compared to higher-income families who were ineligible. Thus, although many ACA policies were adult-focused, low- and middle-income families with children have substantially benefitted from reduced financial burden. Policy makers and child health advocates should work to preserve and improve policies that increase coverage and affordability for parents, as well as those that directly address children’s health care coverage.

Key Facts

- Affordable Care Act (ACA) policies directed at adults may improve health care-related financial burden for families with children by directly increasing affordable coverage both for children and for their parents.

- Following the ACA, reductions in out-of-pocket costs have been greatest for low- and middle-income families.

- Policy makers and child-health advocates should work to preserve and improve ACA policies that have increased coverage and affordability for all parents and their children.

The ACA implemented several policies to improve insurance-coverage access and affordability. These included Medicaid expansion for those with incomes ≤138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and the creation of the ACA Marketplaces. Marketplaces allow those without access to affordable employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) to purchase insurance, often with assistance of premium subsidies known as Advanced Premium Tax Credits (APTCs), for those with incomes ≤400 percent FPL, and cost-sharing reductions (CSRs), for those with incomes ≤250 percent FPL.[1] These policies have reduced out-of-pocket (OOP) health care costs, problems paying medical bills, and financial burden for adults.[2]

Facilitating parental coverage through Medicaid expansion has increased the likelihood that eligible but unenrolled children will obtain Medicaid or CHIP coverage (“welcome mat” effects).[3] It has also improved preventive care use for previously eligible and covered children.[4] Thus, ACA policies directed at adults may improve health care-related financial burden for families with children by directly increasing affordable coverage both for children and for their parents.[5] Reductions in health care-related financial burden for families could further confer benefits by reducing overall family financial strain and allowing more money for other important needs.[6] This is all the more important during periods of public health and economic disruption such as the COVID-19 pandemic.[7]

Importantly, the mechanism by which the ACA impacts families with children may vary by income. In our study, we sought to evaluate financial burden, both from annual OOP health care costs and health insurance premiums, for families with children.[8] We then sought to determine the extent to which family health care-related financial burden was reduced after the implementation of the Medicaid expansion and Marketplace provisions of the ACA.

Measuring Changes in Health Care-Related Financial Burden

We used data from the 2000-2017 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), a nationally representative survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized population that collects data on health care spending and detailed sociodemographics. Our sample included 92,165 annualized families with at least one child (ages ≤18) and at least one adult parent/guardian (ages ≥19). This sample includes 51,815 unique families, of whom 77.9 percent contribute two years of data. Although we did not include families with only young adult (ages 19-25) children, our sample included 16,708 annualized families with both a child ≤18 years as well as a young adult dependent.

We included families with any insurance type, including no insurance. Respondents provided detailed data on annual OOP costs and income, which were adjusted for inflation. Respondents with private insurance provided detailed data on their insurance plans, including their annual premium contributions from 2001 on. We defined OOP costs as all payments for health care expenses for all family members in a given calendar year, excluding insurance premiums. Family income included income from all sources from all family members, with a $100 floor to account for zero or negative incomes. We defined high financial burden using income-based thresholds, for example,as OOP costs exceeding 3.45 percent of income for families with income <$20,000 or OOP costs exceeding 8.35 percent of income for families with income at $75,000, and extreme financial burden as OOP costs ≥10 percent of family income. We examined the prevalence of OOP and premium burden pre- vs post-ACA and by eligibility groups, using a difference-in-differences estimator to assess the post-ACA change for each eligibility group compared to reference families (those not targeted by ACA policies).

Greatest Reductions for Low-Income Families with Children

Across all years, 13.9 percent of families experienced high OOP burden, 5.1 percent experienced extreme OOP burden, and 12.1 percent experienced premium burden. The prevalence of high and extreme OOP burden decreased significantly from the pre- to post-ACA period overall (14.9 percent to 10.2 percent and 5.5 percent to 3.6 percent, respectively). The prevalence of premium burden increased significantly from 11.6 percent pre- to 13.9 percent post-ACA.

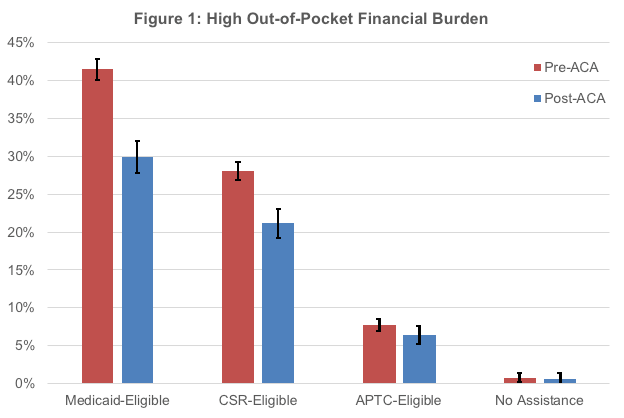

Adjusted difference-in-differences estimates revealed that the ACA’s effect on reducing high financial burden was largest for Medicaid-eligible families, with a change in burden compared to no assistance families of -11.4 percent, followed by CSR-eligible families (-6.8 percent) and APTC-eligible families (-1.2 percent) (see Figure 1). The ACA also reduced extreme financial burden for Medicaid-eligible families (-6.0 percent) and CSR-eligible families (-2.0 percent) compared to families ineligible for assistance.

We identified substantial reductions in health care-related OOP burden for US families with children after the implementation of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and Marketplace CSR and APTC subsidies (Figure 1). These ACA policies, which primarily targeted low- and middle-income adults who were most vulnerable to experiencing high financial burden before the ACA, have likely indirectly benefited children by reducing financial burden in their families. However, despite these gains, financial burden in low- and middle-income families remains markedly higher than that of high-income families following the ACA.

We found that families with children and income-eligibility for Medicaid expansion and/or Marketplace plans with CSRs were most likely to benefit from the ACA’s moderating effect on financial hardship. However, concurrently, we found that, at modestly higher incomes (>250 percent of FPL), the benefits of the ACA appear to be less marked. Although modest reductions in high (but not extreme) financial burden were noted, many of these middle-income families may still experience financial burden from high-deductibles and other out-of-pocket requirements in Marketplace plans without the benefit of CSRs.

Preserving or Increasing Coverage Is Important for Reducing Financial Strain

Extending Medicaid expansion to other states could indirectly benefit children by increasing coverage for parents/family members and improving access to affordable health care. Streamlining Medicaid/CHIP enrollment for children via “no wrong door” policies in state and federal ACA Marketplaces can enhance the impact of ACA policies targeted at adult coverage to increase coverage for eligible but previously unenrolled children. Revising the definition of “affordable coverage” as it pertains to eligibility for Marketplace credits may also be warranted.

Threats to the ACA and its components could directly negate the improvements to family financial burden demonstrated in this study and have other indirect negative effects on children. Such threats are particularly worrisome in situations like COVID-19 or other economic downturns if parents lose job-related coverage and need to turn to Medicaid or the Marketplaces for insurance coverage. Policy makers and child-health advocates should work to preserve and improve policies that increase coverage and affordability for parents, in addition to policies that directly address children’s health care coverage. Doing so can reduce health care-related financial strain in families with children that can lead to delayed and /or forgone care due to cost, with the goal of improving children’s access to needed care and family wellbeing.

For further details, please read the full study: JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(11):1032-1040. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3973

Lauren E. Wisk is an Assistant Professor in the Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research at UCLA, Lecturer of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, and a Research Associate in the Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital. Alon Peltz is a pediatrician and health services researcher at Harvard Medical School. Alison Galbraith is an Associate Professor in the Department of Population Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

References

[1] Explaining Health Care Reform: Questions About Health Insurance Subsidies. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; Jan 16 2020.

[2] Blavin F, Karpman M, Kenney GM, Sommers BD. Medicaid Versus Marketplace Coverage for Near-Poor Adults: Effects On Out-Of-Pocket Spending And Coverage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(2):299-307.

[3] Hudson JL, Moriya AS. Medicaid Expansion For Adults Had Measurable ‘Welcome Mat’ Effects On Their Children. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1643-1651.

[4] Venkataramani M, Pollack CE, Roberts ET. Spillover Effects of Adult Medicaid Expansions on Children’s Use of Preventive Services. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6).

[5] DeVoe JE, Tillotson CJ, Angier H, Wallace LS. Predictors of children’s health insurance coverage discontinuity in 1998 versus 2009: parental coverage continuity plays a major role. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(4):889-896.

[6] Wisk LE, Witt WP. Predictors of delayed or forgone needed health care for families with children. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):1027-1037.

[7] Karpman M, Gonzalez D, Kenney GM. Parents Are Struggling to Provide for Their Families During the Pandemic: Material Hardships Greatest among Low-Income, Black, and Hispanic Parents. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; May 2020.

[8] Wisk LE, Peltz A, Galbraith AA. Changes in Health Care-Related Financial Burden for US Families with Children Associated with the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Sep 28;e203973. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3973. Online ahead of print. PMID: 32986093 PMCID: PMC7522777.