Public Insurance Covers Children When Parents Lose Their Jobs

By Jessamyn Schaller and Mariana Zerpa, the University of Arizona

During the most recent economic recession in the U.S., many parents lost their jobs. When a parent loses a job, it can impact their child’s well-being in complex ways. In a new study, we sought to understand how a parent losing a job affects their children’s health. We found that after a job loss, an increase in public coverage offset much of the decrease in private coverage. In addition, we found almost no effects on children’s use of routine health care services and no evidence that job loss negatively affects children’s physical health in the short run. However, we do find that parental job loss results in a deterioration of mental health for some children, which may have negative implications for child health in the long run.

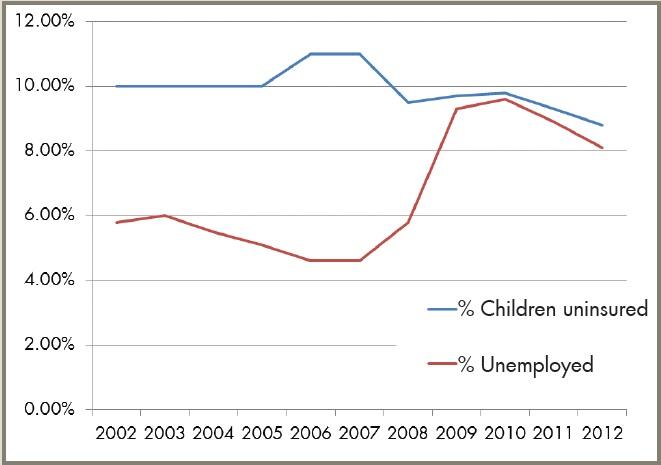

During the most recent recession (2007-10), 8.7 million workers lost their jobs. It was the worst recession since Great Depression in the 1930s. Compared to previous post-war recessions, not only was this recession’s rate of job loss significantly higher, but the rate of re-employment was lower and the average duration of unemployment was longer.

Key Facts

- Public health insurance programs such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) appear to provide an effective safety net for children by effectively mitigating the effects of parental job loss on children’s health insurance coverage.

- After parental job loss, children’s likelihood of health insurance coverage falls by only four percentage points, and their likelihood of receiving routine medical care is unaffected.

- There is no evidence that parental job loss has detrimental effects on child physical health in the short run, though it does have negative mental health effects for some subgroups.

- Parental job loss is associated with a reduction in the incidence of infectious disease among young children, which may be related to a reduction in daycare attendance.

Children are affected when parents lose their jobs. Parents’ stress might cause their children to experience more stress themselves. It might even affect the quality of care a parent can provide. The stress mechanism may be stronger in families for whom displacement is an especially large or sudden shock, and for disadvantaged families who have fewer resources to help them absorb it.

Often, parents pass down their socioeconomic status to their

children, and part of this may be linked back to child health.

Loss of income can affect parents’ investments in nutritious food

and preventive health care. Previous studies have shown that a

child’s physical health also influences their adult health, and

that mental health problems during childhood can negatively

influence future education and earnings.[1]

Measuring Child Health

An important aspect of our study was to understand how a parent losing a job affects their children’s health. We analyzed data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) covering 1996-2012. This large-scale, representative survey collects detailed information on parent-reported health status, health conditions and health care and prescription drug utilization.

To study the effects of parental job loss on children’s health,

we used a large sample of children with displaced parents by

combining data from 16 waves of the MEPS. We limited our sample

to children who were 0 to 16 years old who had at least one

parent employed at the first interview.

In our sample of 54,791 children, 7,900 of them had at least one

parent who lost their job after the first round of the survey. We

focused on involuntary displacements, defining job loss as the

result of a job ending, a business closure or a layoff.

Compared to children whose parents were never displaced, the

children of displaced workers were on average slightly younger,

more likely to be either Black or Hispanic and less likely to

have parents with a college education. These children were also

less likely to have private insurance.

To determine the impact a parent’s job loss had on their

children’s health, we considered changes in health outcomes

before and after a job loss. We considered three categories of

outcome variables:

- Whether the child is covered by any insurance, and the source of insurance (private or public).

- Whether the child visited a doctor and the purpose of the visit, as well as prescription drug purchases.

- Children’s physical and mental health as reported by their parents, as well as any reported medical conditions.

Job Loss and Child Health

While parental job loss does result in a 14.4-percent decline in private insurance coverage, this effect is largely counteracted by a 12.4-percent increase in the likelihood of public coverage through public insurance programs such as Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). As a result, the likelihood that children will have insurance coverage from any source following a parent’s displacement falls by only four percent.

Our analysis suggests that overall parental job loss has no significant effects on reported general health and mental health in the short run. We do see reductions in the incidence of ear infection and infectious diseases. These effects are concentrated among maternal job losses and for children aged 0-4, which suggests that they may be related to a reduction in daycare attendance.

We find only a marginally-significant increase in the likelihood of mental disorders after a parent’s job loss among Black children and among the children of less advantaged parents. These groups on average have fewer family resources with which to buffer the negative effects of a job loss. We do not find these effects among White or Hispanic children or the children of college-educated parents.

It appears that family income shocks and changes in insurance coverage do not substantially affect the use of routine medical care. Meanwhile, we find a significant reduction in the likelihood of a diagnostic doctor visit for children aged 0 to 4, which may reflect the reduction in the incidence of infectious illnesses for this age group. We also find reductions in prescription drug use that mirror the declines in infectious diseases.

Controlling for the local unemployment rate has almost no effect on our displacement coefficients. Meanwhile, we find that increases in the state unemployment rate are independently associated with lower likelihood that parents report that a child to be in excellent physical or mental health and a higher likelihood of a child experiencing asthma and infectious disease.

Importance of Public Health Coverage

Our findings suggest that changes in how displaced parents use their time outweigh the short-run negative health effects on children of a lost job, income and insurance, as well as increased stress. The impact includes the nature of their childcare arrangements while out of work.

Our findings are perhaps surprising in light of existing research demonstrating that job loss has negative effects on adult health and mental health outcomes. One possible reason why the effects on children’s health are less negative than comparable estimates for adults is that public health insurance programs such as Medicaid and CHIP mitigate the effects of job loss on children’s health insurance coverage. As the share of the population eligible for Medicaid is expanded through the Affordable Care Act, this safety net may become larger still.

Jessamyn Schaller is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Arizona.

Mariana Zerpa is a Ph.D. candidate in Economics at the University of Arizona.

This project was supported in part by the Center for Poverty Research Small Grants program.

[1] Currie, J. 2009. “Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: Socioeconomic Status, Poor Health in Childhood, and Human Capital Development,” Journal of Economic Literature.

#povertyresearch