Prejudice and Supervisors’ Race May Impact Wages for Black Workers

By Timothy Bond, Purdue University Krannert School of Management and Jee-Yeon K. Lehmann, Analysis Group, Inc.

During a job interview, workers cannot tell whether an employer is prejudiced. However, they can observe the race of a potential supervisor. In a new study of racial inequality in the labor market, we tested a model of Black and White workers’ wages and job stability using a unique dataset that includes the race of the worker’s supervisor and state-level measures of prejudice. Our findings suggest that higher levels of prejudice in the state may cause Black job applicants to accept lower wages in exchange for the security of working for a Black supervisor. This could lead to lower average wages for Black workers.

Fifty years after major civil rights legislation, a significant economic gap between Black and White Americans remains. Differences in family structure, geography, education and health can explain a significant portion of this disparity. However, many Black families’ inability to rise above poverty is undoubtedly related to persisting racial gaps in jobs and income, particularly among low-skilled workers.

Key Facts

- Black workers earn 4.3% less in firms that have a Black supervisor than in firms without one despite individual worker and employer characteristics, differences in occupation and industry and economic shifts from year to year.

- Black workers are about 6 percentage points less likely than White workers to remain employed after 1 year when working in firms without a Black supervisor.

- An increase in state-level measures of prejudice of one standard deviation leads to an 11% decrease in the wages that Black workers will accept when working with Black supervisors.

- These results suggest that the inability to identify prejudiced employers may help explain Black workers’ lower wages.

These disparities have implications for families in poverty. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 27 percent of Blacks in the U.S. live in poverty. This rate is nearly three times the rate for non-Hispanic Whites. Black workers also lag significantly in jobs and wages. A 2011 study[1] found that Black men experience 176 percent more weeks unemployed than White men. From 2000-10, year-round full-time employed Black men earned less than 80 percent of the income earned by White men.[2]

Some of the wage gap can be attributed to differences in skill,[3] but this alone does not fully explain these disparities, especially for blue-collar workers. Persistent racial disparities suggest varying frictions in the labor market, including prejudice.

Measuring Prejudice and Employment

In a new study,[4] we explored these frictions with an economic model of how Black workers’ perceptions of prejudice can affect their wages and job stability. We then tested this model’s predictions using longitudinal data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 cohort (NLSY97) and the 1998-2010 waves of the General Social Survey (GSS).5

The NLSY97 provides data on workers’ wages and employment, as well as their supervisors’ race. The GSS is a nationally representative annual survey of social attitudes in the U.S. From GSS data, we estimate levels of prejudice by state.

Our sample includes 34,123 observations, 31,666 of which have a valid state-level measure of prejudice. The average wage for White workers in the sample is $15.41/hour, while Black workers earn $12.84 on average. Twenty-eight percent of Black workers earn below $9/hour, while only 16 percent of White workers earn below that wage.

To further account for differences in ability, we controlled for workers’ ASVAB test scores. The test is a multiple-aptitude battery that helps predict academic and occupational success in the military.

Prejudice and Professional Segregation

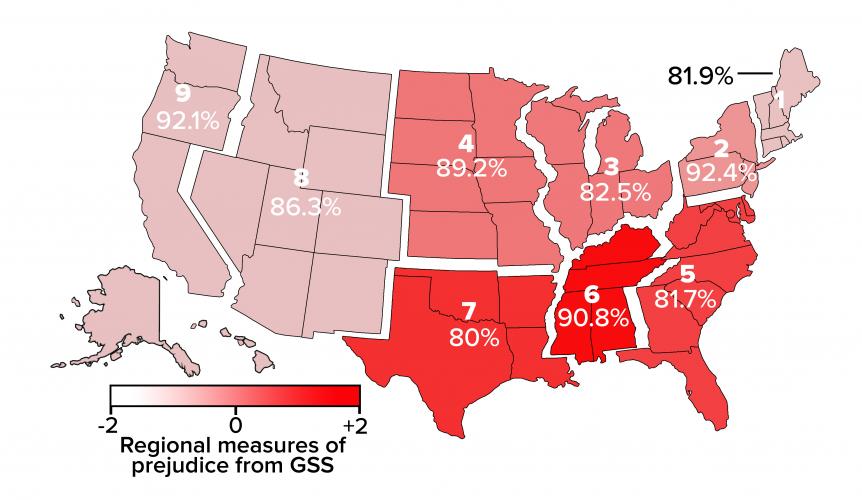

In spite of progress made over the last half century, regional differences in prejudice against Black Americans still exist based on GSS data (see Figure 1). There is also a startling amount of implied occupational segregation by supervisor’s race. In our sample, Black workers make up 76 percent of those with Black supervisors, but just 20 percent of those with White supervisors. Only eight percent of Whites work at an establishment in which they encounter a Black supervisor, compared to 54 percent of Black workers. Among both Black and White workers, those working for a Black supervisor earn less, are less educated and score in lower percentiles of the ASVAB than those who work for White supervisors.

Wages, Stability and Prejudice

Our results show that Black workers earn 4.3 percent less at firms that have a Black supervisor compared to firms with no Black supervisors. This finding includes controls for worker and employer characteristics, differences in occupation and industry, and economic shifts from year to year. Wages for White workers do not vary with supervisor race when controlling for worker characteristics.

At establishments without Black supervisors, controlling for differences in ASVAB test scores reduces the racial wage gap by half, but it has no discernible impact on wages among Black workers. This suggests that wage differences are not driven by unobservable differences in the types of firms where we observe Black supervisors.

Differences in job stability between Black and White workers depend on the race of their supervisors. Black workers at firms without a Black supervisor are about six percentage points less likely than White workers to remain employed there after one year. This difference decreases to less than one percentage point at firms with a Black supervisor.

Prejudice may also impact stability. As state-level measures of prejudice increase, White workers with Black supervisors are less likely to be laid off. Black workers, however, experience no change in job stability. Including controls for tenure, experience, industry, year and census division, a one standard deviation increase in prejudice (which roughly corresponds to moving from Census Division 1 to Division 4) leads to an 11 percent decrease in the wages Black workers will accept at establishments with Black supervisors, and a six percentage point widening of the wage gap between Black workers with White supervisors and Black workers with Black supervisors.

Lower Wages for More Stability

The continued existence of prejudice in job markets implies that policies that simply increase the number of Black supervisors and leaders in business may not necessarily increase wages for Black workers. This study suggests that Black workers will accept lower average wages for jobs with a Black supervisor in anticipation of more stable employment. As the level of prejudice increases in the state, the risk of instability from employers without Black supervisors increases and the negative wage and job stability effects are magnified.

Non-prejudiced employers may find it beneficial to invest in policies, like affirmative action, that signal their lack of prejudice. However, if a national policy, such as affirmative action, does not directly remedy prejudice, it could reduce information on prejudice in the job market. As a result, Black workers may be more willing to accept lower-wage jobs at firms they can ascertain with certainty are unprejudiced.

Timothy Bond is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics of the Krannert School of Management at Purdue University.

Jee-Yeon K. Lehmann is a Manager at Analysis Group, Inc., Boston.

This research was supported in part by a Center for Poverty Research Small Grant. It was conducted with restricted access to Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the BLS.

[1] Ritter, Joseph A. et al. 2011. “Racial Disparity in Unemployment.” Review of Economics and Statistics.

[2] Lang, Kevin et al. 2011. “Racial Discrimination in the Labor Market: Theory and Empirics.” Journal of Economic Literature.

[3] Neal, Derek A. and William R. Johnson. 1996. “The Role of Premarket Factors in Black-White Wage Differences.” Journal of Political Economy.

[4] Bond, Timothy, et al. “Prejudice and Racial Matches in Employment.” Working Paper.

[5] Some of the data are from GSS Sensitive Data Files obtained under special contractual arrangements designed to protect the anonymity of the respondents. These data are not available from the authors. Persons interested in obtaining this data should contact the GSS at GSS@NORC.org.

#povertyresearch