Long-acting Reversible Contraceptives Reduced Teen Pregnancies, Especially in Higher-poverty Areas

By Jason Lindo and Analisa Packham, Texas A&M University

Despite a near-continuous decline over the past 20 years, the teen birth rate in the United States continues to be higher than in other developed countries. Many have advocated for long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), which are more effective at preventing pregnancy than more commonly used contraceptives. In a new study, we analyze Colorado’s Family Planning Initiative, the first large-scale policy intervention to improve access to LARCs in the U.S. We find that the program reduced the teen birth rate by about five percent, and these effects were concentrated among Colorado counties with higher rates of poverty.

Efforts to reduce unintended pregnancies in the U.S., particularly among teens, typically involve attempting to delay or reduce sexual intercourse and/or increasing the use of contraception. While the teen pregnancy rate has been declining, it remains unclear precisely which specific types of policy interventions, if any, contribute to this trend.

Key Facts

- Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) include intrauterine devices (IUDs) and sub-dermal implants and can protect against pregnancy for up to 12 years. Their “typical use” success rate is 99.9% versus 91% and 82% for oral contraceptives and condoms, respectively.

- Colorado’s Family Planning Initiative (CFPI), which increased access to LARCs, is estimated to have reduced teen birth rates by 5% across its first four years, and 7% in its second through fourth years, over and beyond the nationwide downward trend in teen births.

- In higher-poverty counties, the CFPI reduced teen birth rates by an estimated 8% in its first four years, and 10% in its second through fourth years.

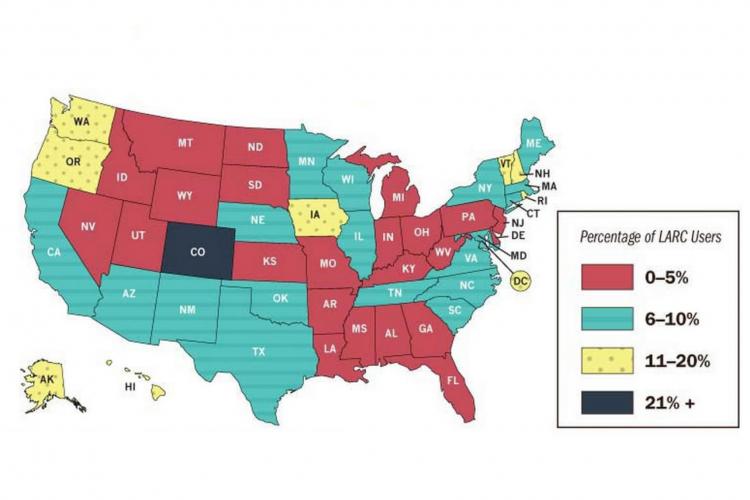

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), include both implants and intrauterine devices (IUDs), and are extremely effective at preventing pregnancy. LARCs have failure rates of less than one percent because they do not require anything of the user for at least three years after the initial procedure. Despite these benefits, only 8.5 percent of all women using contraceptives in the U.S. used a LARC in 2013.[1]

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics state that LARCs should be “first-line recommendations” for all adolescents. They were the focus of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s April 2015 report, “Preventing Teen Pregnancy.” Even so, only five percent of U.S. teens using contraceptives are using a LARC.[2]

In January 2009, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (DPHE) implemented the Colorado Family Planning Initiative (CFPI) with $23 million in provisional funding from an anonymous donor to provide free LARCs to low-income women in Title X clinics. All of Colorado’s 28 agencies accepted funding, which was distributed to Title X clinics in 37 counties through June 2015, when funding for the program ran out.

Title X clinics are federally funded centers providing family planning and preventive health services for low-income women and men. At Colorado Title X clinics, anyone at or below 100 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) pays nothing for care, and patients who earn between 101-250 percent of the poverty level pay a discounted rate. In Colorado, 90 percent of Title X clients have incomes at or below 100 percent of the FPL.

In the years following the CFPI, teen birth rates in Colorado fell by approximately 40 percent. The State of Colorado used that as evidence of the program’s success. However, teen birth rates fell significantly all across the U.S. over the same time period. In a new study, we separate out the effects of the CFPI from these other factors and find that the program did reduce the teen birth rate, though not by as much, and these effects were concentrated in Colorado counties with the highest rates of poverty.

Measuring Change in Teen Birth Rates

To separate the effects of the CFPI from the nationwide downward trend, we compare changes in teen birth rates in Colorado counties with Title X clinics to the change in other U.S. counties with Title X clinics. We focus on teens aged 15 to 19. We additionally control for county-specific and year-specific characteristics, including changes in demographics and the unemployment rate, state-specific trends, and state-level policy controls for insurance mandates and emergency contraception.

The locations of Title X clinics in Colorado come from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment’s Directory of Family Planning Services. We geocoded counties with Title X clinics outside of Colorado by addresses listed in the Department of Health and Human Services’ 340B Drug Pricing Database, which contains over 90 percent of U.S. Title X clinics. In total, the analysis includes 72 percent of U.S. counties, accounting for 93 percent of teenage girls in the U.S.

Data on teen births comes from 2002-2013 restricted-use natality files from the National Center for Health Statistics. These data consist of a record of every birth taking place in the country over this period, including the mother’s age and the county of the birth. We use these data in conjunction with population counts from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER).

Larger Impact in Higher-poverty Counties

The CFPI led to significant reductions in teen birth rates. Our estimates indicate that it reduced teen birth rates across participating Colorado counties by five percent across four years. The magnitude of these effects imply that the program prevented over 900 teen births through 2012.

These effects were concentrated among counties with the highest rates of poverty. We separately estimated effects for counties with poverty rates above the median of counties with Title X clinics.[3] Colorado is a relatively low-poverty state and, thus, that the median being used here at 12.2 percent is lower than the 15.6 percent in counties with Title X clinics outside Colorado.

In higher-poverty counties, the CFPI reduced teen birth rates by six to eight percent over four years. These effects are concentrated in the second through fourth years of the program, at nine to ten percent across these years. Among Colorado counties with lower poverty rates, the initiative reduced birth rates by roughly half as much.

Reducing Unintended Teen Pregnancies

This study shows that programs which promote and subsidize the cost of LARCs, such as the CFPI, can reduce unintended teen pregnancies. Sexually active teens have unintended pregnancies at twice the rate of older women.[4]

Affordable Care Act provisions for preventative health are expected to reduce LARC costs for many women. However, the uninsured cost of LARCs, typically over $500, will remain relevant to women who continue to be uninsured, on grandfathered or exempted plans and to teens concerned that their parents will find out they are sexually active if they obtain contraceptives through their insurance.[5] The newly approved IUD Liletta is also expected to lower costs for insured women and for Title X health clinics.

The results of this study indicate that increasing the availability of LARCs and decreasing their cost could significantly reduce the number of unintended pregnancies, especially among low-income teens. Policies aimed at reducing unintended pregnancies have the potential to improve teenagers’ welfare while reducing challenges associated with teenage childbearing.

Jason Lindo is an Associate Professor at Texas A&M University.

Analisa Packham is a Ph.D. candidate in Economics at Texas A&M University.

1 Guttmacher Institute. 2014. “Contraceptive Use in the United States.” Fact Sheet.

2 Authors’ calculation using the 2011-2013 Survey of National Survey of Family Growth.

3 Average of each county’s 2002-12 poverty rate for a balanced panel.

4 Finer, L. B. 2010. “Unintended Pregnancy Among U.S. Adolescents: Accounting for Sexual Activity.” Adolescent Health.

5 68% of teens report the primary reason to not use birth control is fear their parents will find out (The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy 2015).

#povertyresearch