Greater Financial Supports Could Improve Household Economic Wellbeing around a Birth

By Alexandra B. Stanczyk, University of Chicago

Household economic security contributes to child and family wellbeing, and is especially important during the rapid developmental periods of infancy and early childhood.[1] My new study shows that, on average, the economic wellbeing of U.S. households falls in the months before and after a birth, especially among parents with low levels of education and single mothers who live without other adults. Timely and more generous income supports and policies facilitating mothers’ employment could boost economic wellbeing during this critical period.

Pregnancy and the arrival of an infant bring new expenses such as healthcare, childcare, clothing and other supplies for the baby. At the same time, mothers’ earnings tend to decline, as almost all U.S. mothers take at least some time off in the months leading up to and following birth.[2] Economic insecurity and instability can increase parents’ stress, reducing the quality of parent-child interactions. It can also interfere with families’ ability to provide adequate housing, good nutrition and safe childcare that promote child health and development.

Key Facts

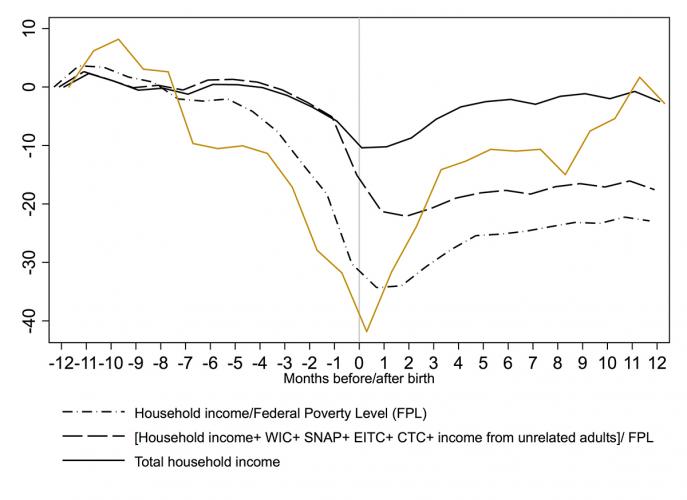

- From pre-pregnancy to the birth month, on average, U.S. households experience a 30.2% decline in income as a share of the Federal Poverty Level and a 10.4% decline in total income.

- Single mothers who live without other adults face significantly larger drops in household income as a share of the Federal Poverty Level (64.8%), and in total income (41.8%).

- Social safety net programs lessen but do not eliminate reductions in household economic wellbeing around a birth.

- More generous and timely income support as well as policies facilitating mothers’ employment could boost household economic wellbeing during this critical period.

Reductions in mother’s earnings may be greater for less-educated new mothers who are unlikely to have access to paid leave. For single mothers living without other adults, earnings declines may have a particularly large impact on household finances, as these mothers cannot rely on another earner. Additionally, low savings and assets among less-educated and single-mother households may make a new birth especially financially difficult.

On the other hand, pregnancy and the growth in household size may trigger an increase in public program eligibility and benefit levels among less-advantaged households. The Special Supplemental Nutritional Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) targets in-kind nutritional assistance to low-income pregnant women, new mothers and children under six.

Many other major U.S. safety net programs including the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC) increase in generosity with the addition of a new child to the assistance unit. However, it is not clear if this rise in assistance around the time of a birth compensates for drops in mothers’ earnings and the additional resources needed.

In a new study, I find that, on average, U.S. households experience significant declines in economic wellbeing around a birth, especially among households with lower levels of education and single mothers who live without other adults. Public programs help, but could do more.

Measuring Changes in Economic Wellbeing

This study is based on monthly information on the level and sources of household income from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). The sample includes births between 1995 and 2013, where the infant’s biological mother is present in the birth month (N=11,615).

I consider results separately by mothers’ educational attainment[3] and by household structure, a major determinant of household financial circumstances. For the full sample and for each subpopulation, I estimate the average percent change in household economic wellbeing from pre-pregnancy (one year before the birth) to each of the 12 months before and after birth month.

I measure household economic wellbeing in three ways. I first calculate household income as a percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). The FPL increases with household size to reflect greater demands on resources, so declines in this measure around the time of a birth reflect both decreases in household income and increased resource needs.

Next, I add income not included in the official poverty measure, such as safety net programs including WIC, SNAP, the EITC and the CTC, as well as income from unrelated household adults. Research shows that not all SIPP respondents report income from these sources, but underreporting is less severe in SIPP than in other major U.S. surveys. Finally, I look at total household income, which includes all income but not as a share of the FPL.

This study considers only cash and near-cash income, as these are most vulnerable to changes around a birth. Subsidized housing, public medical insurance, and in-kind donations from private organizations, friends or family are not included, but may buffer declines in income for some households.

Economic Wellbeing Falls around Birth

On average, U.S. households experience 30.2-percent declines in income as a share of the FPL, and 10.4-percent declines in total household income from pre-pregnancy to the birth month. Total household income recovers to pre-pregnancy levels around the infant’s fourth month, while household income as a share of the FPL does not recover in the year following birth.

Households in which the birth mother has only a high school degree experience significantly greater drops in household income as a share of the FPL than families in which the mother has a bachelor’s degree or above (35.6% and 13.9%, respectively). Single mothers who live without other adults are particularly vulnerable to declines in economic wellbeing around a birth. This group, on average, experiences 64.8-percent declines in household income as a share of the FPL and 41.8-percent declines in total household income from pre-pregnancy to the birth month.

Across all subpopulations, drops in household income as a share of the FPL are smaller–but still significant–after I add income sources not included in the official poverty measure. This finding suggests that these income sources, which include benefits from several major social safety net programs, bolster household economic wellbeing in the time around a birth. Still, they do not fully compensate for reductions in earnings and increases in demands on resources associated with the arrival of an infant.

Supporting Families and Infants

This study shows that all U.S. households-and particularly low-educated households and single mothers who live without other adults-face heightened risk of declines in economic wellbeing during pregnancy and following birth. Cash and near-cash safety net programs buffer these declines but households still come up short.

Increasing the generosity of these programs, could boost economic wellbeing in this critical period. Timeliness may also be an issue. Households may not receive EITC and CTC benefits until tax time, which may be well after a birth. A child benefit policy, common in other industrialized nations, could provide timely income support.

Additionally, policies supporting employment, such as paid family leave and more generous childcare subsidies, could increase household economic wellbeing around a birth.

Alexandra B. Stanczyk is a Ph.D. candidate in Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago. She was a Center for Poverty Research Visiting Graduate Scholar in 2014.

1 Magnuson, K., et al. 2009. “Enduring influences of childhood poverty.” Changing Poverty, Changing Policies. Russell Sage Foundation.

2 Laughlin, L. 2011. “Maternity leave and employment patterns of first-time mothers: 1961-2008.” U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Reports.

3 A common proxy for household socioeconomic status in studies of work and income around birth.

#povertyresearch