DACA Uncertainty May Undermine its Positive Impact on Wellbeing

By Caitlin Patler, Erin Hamilton and Robin Savinar, UC Davis

Young, undocumented Latino immigrants face many challenges in the United States. Undocumented Latino youth are less likely to graduate from high school and attend college than native-born youth and are more likely to live in poverty and report clinical levels of depression. Our research examines the impact of changes in legal status related to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program on Latino immigrant young adults in California, with a focus on distress and psychological wellbeing. Our results show that levels of distress for DACA-eligible young adults dropped significantly in the 2013-14 time period after DACA’s implementation. However, by 2015-16, their distress levels began to increase when many became aware of the program’s limitations and possible termination.

Key Facts

- Young Latino immigrants have reduced access to healthcare, education, employment and higher rates of clinical depression, and DACA-eligible young people face poverty rates of up to 30%.

- Our study of data from California shows that DACA-eligible young people had a significantly lower distress level in the post-DACA period (2013-14) than in the pre-DACA period (2007-11), compared to documented immigrants.

- By 2015-16 initial improvements in psychological wellbeing declined, perhaps due to uncertainty about the program’s future.

The United States is home to 11 million undocumented immigrants, including five million children and young adults under age 30, the majority (78 percent) of whom are from Latin America.[1] Young Latino immigrants are more likely to live in poverty and have higher rates of clinical depression than native-born youth.[2,3] Evidence suggests that DACA-eligible young adults faced poverty rates of 30 percent in the years just prior to the program.[4] In addition to poverty, undocumented immigrants in the U.S. face many other challenges, including reduced access to healthcare, higher education, qualified jobs, and political participation.[1,5] To explore the disparities between undocumented immigrants and the native-born, researchers have studied whether inequalities in legal status are partly responsible.

DACA Presents a Unique Opportunity to Study the Impact of Gaining Temporary Legal Status on Psychological Wellbeing over Time

Our new study examines the impact of changes in legal status related to the DACA program on the psychological wellbeing of young, undocumented Latino immigrants in California from 2007-16. The DACA program was announced by President Obama in June of 2012 and sought to provide legal status to young people who had arrived with their undocumented parents as children, providing them with a means to pursue their lives legally in the United States. However, in September 2017, the Trump administration announced plans to phase out the program, making DACA’s future uncertain.

Our study looked at the psychological wellbeing of DACA recipients in California both before and after receiving DACA. We focused on California, as the home to 26 percent of all DACA recipients, and we drew on two sources of data: the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) and the DACA Study, which uses original longitudinal data and in-depth interviews with 502 Californians who considered applying for DACA.

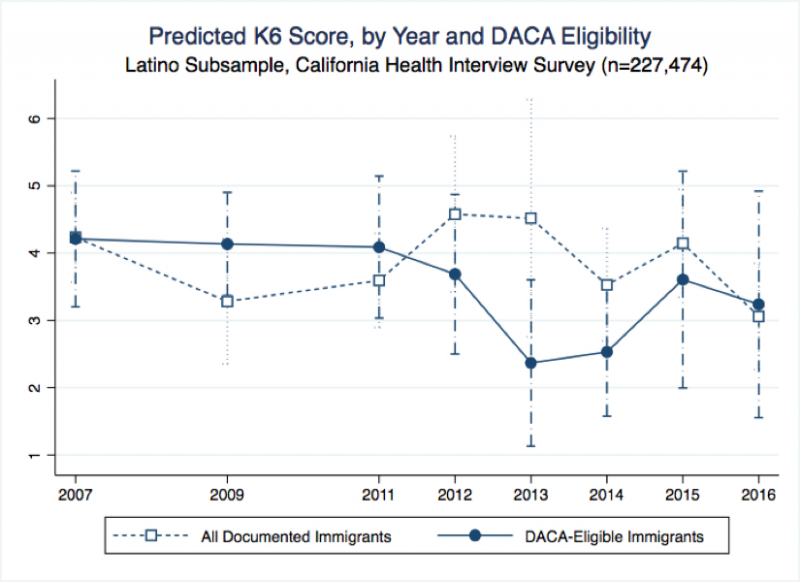

We analyzed information on participants’ psychological wellbeing in a pre-DACA period (2007-11) compared to a post-DACA period (2013-16). We measured psychological wellbeing using the Kessler Six-Question Psychological Distress Scale (K6), which is one of the most widely used scales to measure the severity of mental health problems. We used a difference-in-differences estimation to compare the DACA-eligible population both to itself prior to DACA, and to an ineligible control group both before and after DACA. The members of the ineligible group were similar to the DACA-eligible except they already had legal immigrant status.

DACA Improved Psychological Wellbeing among Latino Immigrant Young People in California in the Short-Term

Our results show that the DACA-eligible had a significantly lower distress level in the 2013-14 post-DACA period than in the 2007-11 pre-DACA period, compared to the control group. Specifically, in the 2013-14 period, DACA-eligible Latino immigrants had predicted distress scores that were 60 percent lower than during the pre-DACA period (2.42 points compared to 4.0 points), whereas the scores of documented immigrants were not statistically significantly different from the pre- to post-DACA period.

The qualitative data provided by the survey and in-depth interview responses to the DACA Study in 2014 help to explain these results. DACA recipients said that the program relieved the chronic stress of deportation from their lives. They reported a newfound sense of security and safety in their temporary status, and they felt less excluded, more optimistic and more integrated into American sociocultural and political life. Recipients also reported that the work authorization provided by DACA helped to relieve the distress related to finding work and the economic hardship they had faced.[6]

Reductions in Distress Related to Receiving DACA Have Diminished Over Time

Despite the positive nature of these preliminary results, a more in-depth look at the data year-by-year shows that distress declined dramatically in both 2013 and 2014 but began to increase again after 2014. By 2015-16, the distress levels of the DACA-eligible were not statistically different from their pre-DACA distress levels.

In order to find out why this might be, we drew on DACA Study interviews from 2015 and 2016, which showed that by that time, many of the DACA-eligible began to realize that the DACA program might not be a permanent solution for them. They pointed to their continued worries about family members who did not qualify for the program and remained undocumented. Some felt that their goals were still out of reach, or they worried about making decisions, because their legal status was not permanent. With the initiation of the 2016 presidential campaign, respondents expressed concern that the program might be rescinded.

Our study supports the idea that providing undocumented immigrants legal status reduces distress and supports psychological wellbeing in the short-term. However, it also suggests that undocumented young people are vulnerable to the stress of the uncertainty and complexity that characterize the DACA immigration policy. If DACA is terminated, people who have had DACA and then lose it may feel even more vulnerable and distressed than they did before the program was announced. Our results suggest that a permanent legalization program would better support the psychological wellbeing of undocumented young people in California.

Caitlin Patler is Assistant Professor of Sociology at UC Davis.

Erin Hamilton is Associate Professor of Sociology at UC Davis.

Robin Savinar is a PhD Candidate in Sociology at UC Davis.

References

[1] Patler, Caitlin, 2017. “Undocumented Disadvantage, Citizen Advantage or Both? The Comparative Educational Outcomes of Second and 1.5-Generation Latino Young Adults.” International Migration Review.

[2] Passel, Jeffery S. and D’Vera, Cohn, 2009. “A Portrait of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States.” Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center.

[3] Potochnick, Stephanie R., et al., 2010. “Depression and Anxiety Among First-Generation Immigrant Latino Youth: Key Correlates and Implications for Future Research.” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease.

[4] Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina and Antman, Francisca, 2016. “Can Authorization Reduce Poverty Among Undocumented Immigrants? Evidence from the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Program.” Economics Letters.

[5] Center for American Progress, 2017. The Facts on Immigration Today: 2017 Edition. Washington D.C.

[6] Turner, R. Jay, et al., 1995. “The Epidemiology of Social Stress.” American Sociological Review.

#povertyresearch