Immigrant Mothers, Community Organizations and Poverty

by Dina Okamoto and Valerie Feldman, UC Davis; and Melanie Jones Gast, DePaul University

Community-based organizations (CBOs) serve low-income immigrants who face significant barriers to public aid. An increasing proportion of these populations includes families with children who live in poverty.

In ongoing research, Faculty Affiliate Dina Okamoto, Valerie Feldman and Melanie Jones Gast find that Latin American immigrant mothers in high-poverty areas rely on CBOs to meet their diverse needs.

Key Findings

- Immigrant mothers are drawn to CBOs for material resources, such as free monthly bus passes, backpacks and shoes for their children as well as direct assistance with housing.

- Information sessions and workshops help immigrant mothers become empowered citizens as well as hubs for information in their communities.

- Since the mothers were in dire need of assistance but wary of government aid, they looked to CBOs to meet their diverse needs. This signals the need for more public funding for programming and outreach, especially for CBOs with the language capacity to serve immigrant populations.

Immigrants from Latin America are among the fastest growing populations in the U.S. While the overall foreign-born population increased four-fold between 1970 and 2000, the Mexican and Central American populations doubled each decade for a twenty-fold increase.(1) An increasing proportion of this population includes families with children who live in poverty.

These newcomers have relatively low levels of education and English proficiency. Many are undocumented and unlikely to have family nearby. These factors all pose significant barriers to systems that promote social mobility.

CBOs facilitate access to education, housing and work. Typically supported by a mixture of public aid and private revenues, community-based organizations (CBOs) have become an important source of support for low-income communities often disenfranchised from larger systems of public aid.

These services are particularly important since these immigrants face eligibility barriers to public aid in the current federal policy environment.(2) Understanding how Latina mothers perceive the role of CBOs and how they use their services will help us to understand the specific ways these organizations impact low-income immigrant families.

Community Demographics

In this study, the researchers conducted interviews in Spanish

with 28 Latina immigrant mothers who participated in San

Francisco-based Adelante Familias (AF) and Padres Unidos (PU)

programs in 2011 and 2012. (The names of the organizations and of

the mothers referenced in this brief are pseudonyms.)

The mothers were asked about their migration and adaptation experiences, as well as their perceptions of and experiences with CBOs and how they use CBO resources to aid in the transition out of poverty. The study also involved over 200 hours of field work at open monthly meetings and workshops held by these CBO programs.

Both AF and PU are small programs, each with one full-time staff member and several volunteers. They provide direct services, material resources and advocacy for low-income immigrant families. They also engage their participants in community organizing around issues related to affordable housing, community development, immigrant rights and neighborhood safety.

These programs are located in the Tenderloin and South of Market neighborhoods in San Francisco, both of which are ethnically diverse and also have the highest poverty rates in the county at 28 and 22 percent, respectively (compared to 8 percent nationwide). Due to their proximity to many service jobs and single-room occupancy hotels, these neighborhoods are destinations for newly arrived, poor immigrant families.

These characteristics make these organizations ideal sites to examine how immigrants living in poor, urban neighborhoods obtain resources when they do not have access to established ethnic communities. In many ways, what we learn from these programs may be helpful in understanding dynamics in other places.

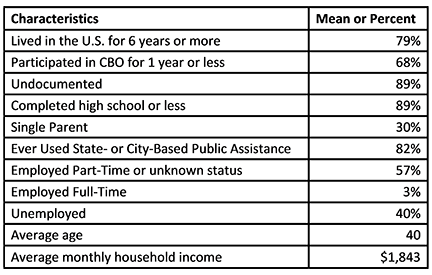

Table 1 shows the general demographics of this sample of Latina mothers. The vast majority were undocumented and had low levels of education and economic resources while raising an average of two to three school-aged children.(3) Despite the fact that many of the mothers were wary of receiving public assistance, over three-quarters of the women had used food stamps and Medi-Cal or Healthy Kids at some point to support the needs of their children.

Their average monthly household income, earned through one or more unstable part-time positions, was about $1,800, which fell short of their average monthly expenses of about $2,150. Many of the Latina mothers regularly struggled to make ends meet due to high rent and living costs which posed significant constraints.

The women also cited other challenges that limited their ability to achieve economic mobility and access to public aid systems, including a lack of English fluency, isolation from familial and friendship networks, undocumented status, racial discrimination, chronic health problems and domestic violence.

The Impact of CBO Programs

More than three-quarters of the women in this sample had been

living in the U.S. for 6 years or more, but a majority had only

recently begun to attend CBO programs. Most heard about AF and PU

through acquaintances, extended family members, neighbors or even

strangers. The women were drawn to the programs for the material

resources provided for children, such as free monthly bus passes,

backpacks and shoes, as well as for direct assistance with

housing. These free items meant that they could save from $20 to

$100 each month, which mothers used to put food on the table.

While some were initially uncertain about participating in CBOs for fear of being reported to immigration authorities, the mothers began to see them as communal spaces where others just like them receive aid in a setting not associated with fear or the government. They also viewed CBOs as places where they were shown respect, and where they could be part of a community of people working together to better their situations.

Selena, a mother of three in her late 20s said of AF, “They as an organization are focused on helping people, [so] that we stop having a bit of fear. And they are people that are focusing on giving us information … They see that we still have rights, and they have papers and everything, but they are trying to help us.”

CBOs also offered a safe and confidential space for undocumented immigrants, where many of the mothers felt comfortable speaking to and sharing their experiences with one another. Susana, a mother of two in her mid-30s explained: “They’ve provided a space for people to listen to us. Every day they make life easier for us. They have and share knowledge about issues that affect us, and make a safe space in the neighborhood that is new for a lot of us.”

Latina mothers also received information from CBOs through weekly or monthly workshops and leadership-building programs in Spanish. To Ilana, gaining information on immigrant rights helped her to feel empowered and part of a community of immigrants: “Every meeting there is always a new topic to learn that opens our minds. It’s good to know of the rights we have as immigrants… We know how to talk, and we know what is good for our kids, too.”

Participants of AF and PU appreciated receiving information from the CBOs for their own benefit, but they also freely shared what they had learned with friends and family members. This indicates that immigrant parents who attend CBO programs can serve as information hubs in their communities.

Furthermore, CBOs combat the potential stigma of receiving public support by providing mechanisms for their participants to give something in return. Some of the women in this sample spoke about volunteering for the organization, or participating in campaigns that were led by the organization in order “to give back,” such as campaigns to fight for city measures or public funding for local CBOs. In other words, CBOs allow immigrants to participate and have direct involvement in community issues that might benefit them and others in their communities.

Limitations of CBOs

Although CBOs provided a variety of resources and information for

immigrant parents, they were not able to address all of their

needs. The Latina mothers noted that the information provided by

CBOs related to upcoming local laws and measures were less

interesting or useful to them than issues that directly affected

their ability to navigate their everyday lives.

For instance, several of the women noted that the presentations on low-income housing and social justice provided by AF were repetitive, and did not necessarily provide the type of detailed information that they desired, such as where to apply for low-income housing and what information is needed for the application process.

Other Latina mothers voiced their dismay that educational programs and workshops provided by AF and PU had ended due to budget cuts, and wanted more workshops because they helped parents to develop useful skills. Many of the mothers requested classes on computer literacy, English language skills and how to obtain American citizenship.

Additionally, immigrant parents had complaints about the availability and limitations of CBO staff members to provide them with services due to language barriers. Although some staff and volunteers at both organizations were fluent in Spanish and English, several respondents felt that more bilingual staff were necessary and that the quality of some staff translations was lacking. Moreover, some mothers complained that the staff was not always available for drop-in support outside of monthly meetings and workshops. (4)

Conclusions

Since these low-income, Latina immigrant mothers were in dire

need of both economic and social assistance but wary of seeking

assistance from government public aid offices, they looked to

CBOs to meet their diverse needs.

This study found that CBOs met a number of these needs by:

- administering direct services and resources in the forms of housing and material assistance;

- providing language translation;

- creating a welcoming, confidential space for all immigrants, regardless of documentation status;

- empowering mothers through skill-building and volunteering efforts; and

- working on behalf of immigrant and low-income communities in civic and political campaigns.

These results point to the importance of maintaining and further developing a nonprofit infrastructure that can provide services and resources for local areas with diverse language, economic, and social needs. It also signals the need for more public aid for CBOs to expand their service capacity and outreach efforts, especially for those with the language skills to serve the needs of immigrant populations.

Meet the Researchers

Dina Okamoto is an Associate Professor of Sociology at UC

Davis. Her reserach on race and ethnicity and immigration have

been funded by the Russell Sage Foundation, the American

Sociological Association, the National Science Foundation and the

William T. Grant Foundation.

Valerie Feldman is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at UC Davis. Her research interests include social change, citizenship, politics and culture.

Melanie Jones Gast is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at DePaul University. Her research interests include race and ethnicity; social class; and children, youth and families.

Notes

1 Brick, Kate, A.E. Cahallinor, and Marc. R. Rosenblum.

2011. Mexican and Central American Immigration in the United

States. Washington, DC, Migration Policy Institute.

2 Fix, Michael E. 2009. Immigrants and Welfare: The Impact of Welfare Reform on America’s Newcomers. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

3 The mothers were eligible for state-based public-aid programs such as CalWORKS, CalFresh food stamps and Medi-Cal, because they had U.S.-born children under the age of 18. Only three of the mothers used CalWORKS, half used food stamps and the majority used Medi-Cal or Healthy Kids for their children. Healthy Kids and Healthy San Francisco are city-based health care programs for low-income, uninsured residents regardless of documentation status.

4 Staff were small in number at each CBO, and were not often in the office because they were attending meetings at City Hall, at other CBOs or doing hands-on work in the neighborhood.

For

further reading

Brick, Kate, A.E.

Cahallinor, and Marc. R. Rosenblum. 2011. Mexican and Central

American Immigration in the United States. Washington, DC,

Migration Policy Institute.

Fix, Michael E. 2009. Immigrants and Welfare: The Impact of Welfare Reform on America’s Newcomers. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Fortuny, Karina and Ajay Chaudry. 2011. “A Comprehensive Review of Immigrant Access to Health and Human Services.” The Urban Institute, Washington, DC.

Marwell, Nicole P. 2007. Bargaining for Brooklyn: Community Organizations in the Entrepreneurial City. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Menjívar, Cecilia. 2000. Fragmented Ties: Salvadoran Immigrant Networks in America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Perriera, Krista M., Robert Crosnoe, Karina Fortuny, Juan Pedroza, Kjersti Ulvestad, Christina Weiland, Hirokazu Yoshikawa, and Ajay Chaudry. 2012. “Barriers to Immigrants’ Access to Health and Human Services Programs.” U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC.

Yoshikawa, Hirokazu. 2011. Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Immigrants and their Young Children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Zhou, Min. 2000. “Social Capital in Chinatown: The Role of Community-Based Organizations and Families in the Adaptation of the Younger Generation.” Pp. 315-35 in Contemporary Asian America: A Multidisciplinary Reader, edited by M. Zhou and J. V. Gatewood. New York: New York University Press.