Supporting Safety Net Hospitals through DSH Payment Cuts and Medicaid Expansion

By Lindsey Woodworth, University of California, Davis

A major component of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was a mandated expansion of Medicaid. The law also prescribed cuts to Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments, which subsidize hospitals with high levels of uncompensated care. For states that have opted out of Medicaid expansion, Medicaid reimbursements will not make up for lost DSH payments. However, DSH cuts may also create additional financial challenges for these hospitals in opt-in states if Medicaid expansion does not reduce overall uncompensated care.

Safety net hospitals care for disproportionately large shares of low-income patients who are either covered by Medicaid or are uninsured. To different extents, both populations generate uncompensated care. Medicaid reimbursements do not always cover the cost of treatment, and uninsured patients do not always provide reimbursement for care.

Key Facts

- The ACA has prescribed cuts to Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH)payments which will take effect nationwide in 2018.

- In the states that have chosen not to expand Medicaid, safety net hospitals’ ability to withstand DSH cuts will depend on low income individuals’ procurement of private coverage.

- In the states that have decided to expand Medicaid, many low- income individuals will gain public coverage, but whether this will alleviate safety nets’ dependence on DSH payments will depend on the extent to which new enrollees increase their use of health care.

To offset uncompensated care, the federal government provides states with DSH payments to distribute to safety net hospitals. These payments are annually allocated to states which then have discretion in determining how to distribute the funds across hospitals with large shares of Medicaid and uninsured patients.

The federal government provides over $11 billion in DSH payments to states each year. The amount given to each state is capped at the larger of either the state’s allotment the previous year or 12 percent of its Medicaid payments in the current year.[1]

The extent to which safety net hospitals rely on DSH payments varies by state. A 2013 report by the Congressional Research Service showed that DSH payments as a percentage of total Medicaid medical assistance expenditures ranged from zero in Massachusetts to more 12.1 percent in New Jersey, at an average of 4.2 percent.[2]

Cuts to DSH Payments

The original rationale for DSH cuts presumed that under the ACA, Medicaid would cover all individuals with incomes up to 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). The associated increased reimbursements for care would alleviate safety net hospitals’ dependency on DSH payments.

At the time of the ACA’s passage, DSH cuts were scheduled to take effect on October 1, 2013. Mandatory expansion of Medicaid was scheduled to take effect on January 1, 2014. If all went as planned, the removal of DSH payments would be replaced by new reimbursements from Medicaid across all 50 states. This did not occur.

In 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case National Federation of Independent Business NFIB v. Sebelius, which challenged the ACA’s constitutionality. The majority of the bill was upheld, but the Court struck down the mandated expansion of Medicaid.

After the decision, if a state chose to expand Medicaid, the federal government would pay 100 percent of the cost of new enrollees through 2016. Federal support would then phase down to 90 percent in 2020. With Medicaid expansion no longer guaranteed, DSH cuts were postponed.

These cuts are now set to take effect in 2018. The annual amount of the cuts will begin at $2 billion in 2018 and then gradually rise to $8 billion in 2025. The largest cuts will be felt by states with low rates of un-insurance and those which do not target DSH payments to hospitals with high numbers of Medicaid patients and with large amounts of uncompensated care.

The loss of DSH payments could make safety net hospitals financially unviable. A 2014 study[3] identified 529 hospitals nationwide for which DSH payments made up at least three percent of their Medicaid expenditures. Of these, roughly 225 – or just over 40 percent – were considered to be in weak financial condition based on the difference between net patient revenues and operating costs. These hospitals are likely to be the most vulnerable to DSH cuts, and are split relatively evenly between states that will and will not expand Medicaid.

DSH Cuts with Medicaid Expansion

Safety hospitals may struggle in states that have chosen not to expand Medicaid.[4] However, it is possible that DSH cuts will also present challenges for safety net hospitals in states that have chosen to expand Medicaid.

Because of high out-of-pocket requirements, many uninsured individuals forego medical care. With new coverage through Medicaid, the newly insured patients may seek more care. Since many providers do not accept Medicaid patients because of their low reimbursement rates, many of these newly covered patients will end up at safety net hospitals.

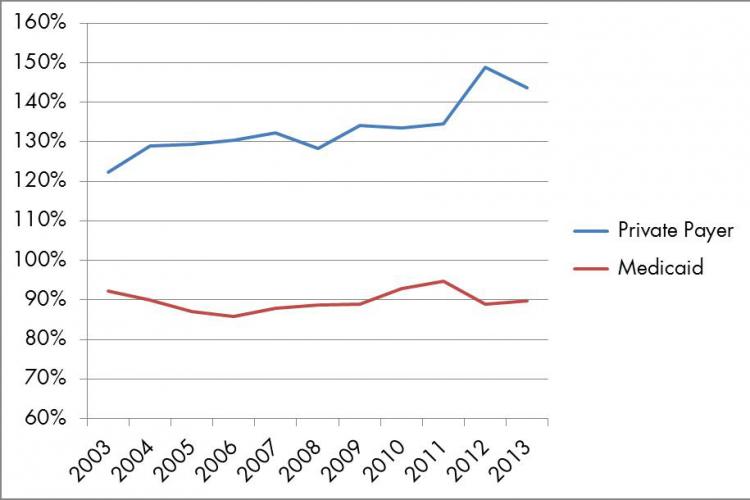

Not only are safety net hospitals financially constrained by high shares of uninsured patients, but also because of high shares of Medicaid patients, which reimburse at lower rates than those with private insurance. In 2013, private insurance paid on average 143.6 percent of cost for services but Medicaid paid 89.8 percent. Figure 1 shows the difference in these payment-to-cost ratios from 2003-13.

If, following Medicaid expansion, increases in Medicaid encounters at safety net hospitals outpace reductions in uninsured encounters, then the number of lower paying encounters at safety nets will rise. The improved uninsured-to-Medicaid ratio will lower the average loss in this pool. However, the weight of the larger pool may generate financial strain on the hospital at large.

Supporting Safety Net Hospitals

For vulnerable populations, the loss of a safety net hospital due to financial insolvency could further reduce their access to care. Many of these individuals rely on safety nets precisely because of inabilities to access care from providers that do not treat the uninsured or those covered by Medicaid. This outcome runs directly counter to the aim of the Affordable Care Act.

It is imperative to consider the financial condition of safety net hospitals in all states. If, within Medicaid-expanding states, operating margins do shrink as a result of having more Medicaid patients, this outcome will be instructive in determining how best to financially support safety net hospitals.

If a future court decision strikes down subsidies for insurance through HealthCare.gov, then an estimated 8.2 million will lose insurance coverage.[5] This could make the effects of Medicaid expansion even more marked. Policymakers should consider these dynamics when ultimately deciding whether to move forward with DSH cuts.

Lindsey Woodworth is an economics post-doctoral researcher at UC Davis. Support for this project was provided by grant #T32HS022236 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) through the Quality, Safety, and Comparative Effectiveness Research Training (QSCERT) Program.

[1] Mitchell, A. 2013. “Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Payments.” Congressional Research Service.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Cole, E., et al. 2014. “Identifying Hospitals that May be at Most Financial Risk from Disproportionate-Share Hospital Payment Cuts.” Health Affairs.

[4] Mullin, J. 2013. “For states not expanding Medicaid, DSH cuts will deal a tough blow.” The Advisory Board Company.

[5] Blumberg, L. et al. 2015. “The Implications of a Supreme Court Finding for the Plaintiff in King vs. Burwell: 8.2 Million More Uninsured and 35% Higher Premiums.” Urban Institute.

#povertyresearch