Supporting Motherhood Capital Could Benefit Children

By Ming-Cheng Lo, UC Davis

In the U.S., low-income immigrants are disproportionately excluded from social services. Even those who have gained formal access must often overcome informal institutional barriers. In a new study, I interviewed low-income Mexican immigrant mothers with limited English skills to understand these informal barriers in education and healthcare settings as they advocated on behalf of their children. The study suggests that mothers are most effective in a less bureaucratized setting and when staff recognize how deeply they care for and understand their children.

Immigrants in the U.S. have limited access to social services, largely due to statutory exclusions written into access policies. Even within institutions that have inclusive policies and service-oriented missions, immigrants can face marginalization. This is often caused by their lack of “cultural capital,” i.e., the informal cultural resources needed to successfully navigate social service institutions, such as knowing how the system works, where to get help and, perhaps most importantly, how to conduct oneself in a style that staff consider knowledgeable, engaged and worthy of respect.

Key Facts

- Immigrant mothers can find it confusing, difficult and cumbersome to navigate through social service institutions while advocating for their children.

- A professionals/mothers alliance would allow these mothers to receive respect and response from professionals and to contribute actively to school and health outcomes for their children.

- A simple and localized bureaucracy, communication that values professionals and mothers as partners in their children’s care and the recognition that immigrants are not only service recipients but also potential contributors or partners would all move toward improving the education and care of children.

Studies[1] show that cultural capital, typically accumulated through long-term socialization in American middle-class families and higher education, is difficult for low-income immigrants to acquire. With little cultural capital, even in the few social service institutions to which they or their children have access low-income immigrants struggle with informal barriers that include complex forms and other bureaucratic steps that seem indecipherable and staff that seem unapproachable or dismissive.

My new study finds that the institutional environment plays an important role in why some low-income immigrants can better address these informal barriers. Certain institutional features encourage immigrant mothers to use their care for and understanding of their children, which I call “motherhood capital,” to enhance their children’s school and health outcomes. Other institutional features do the opposite.

Interviews with Immigrant Mothers

I compared a group of low-income Mexican immigrant women’s experiences across two settings: at schools and at healthcare facilities. As part of the U.S. social safety net, K-12 public schools and certain types of health care services[2] are two of the few institutions accessible to children of low-income immigrants.

The 25 Mexican-born interviewees all had limited English proficiency (LEP). Most interviewees (19) were undocumented immigrants, and all were of low socio-economic status. Their experiences do not describe the circumstances of disadvantaged immigrant mothers at all schools and health care institutions, but they do illustrate examples of challenges these mothers can face and some possible solutions.

This study is part of a larger project on immigrant wellbeing in the “Valley City” (pseudonym) metropolitan area in Northern California. Valley City is one of the most racially diverse cities in the US, and the metropolitan area has a sizable Latino/a population.

Emerging Alliance at Schools

At their children’s schools, the mothers felt that their main goals were easy to achieve through collaborations with teachers. The schools’ institutional features; such as a well-coordinated bureaucracy, interactive relationships with teachers and the dominant view of Mexican immigrant mothers as active contributors; created environments that valued them as mothers.

Felicia[3] described how teachers respected her contributions as a mother and her intimate knowledge about her children’s personalities. She recalled when her daughter’s second-grade teacher asked for advice about how to address the girl’s excessive shyness: “I gave them some ideas and I noticed that [my ideas] worked [for my daughter] and even for a number of other kids.”

Perla felt burdened by her limited cultural capital to the point that, “I don’t want to say anything, because I’m afraid that what I might say wouldn’t come out right… even when they speak Spanish.” While Perla seemed to struggle much more than the other mothers, her daughter’s high school counselor encouraged her to attend a parent-teacher meeting when her daughter’s grades dropped. Perla was pleasantly surprised that she interacted well with the teachers and offered several useful suggestions.

While most Latino parents strongly value their children’s education, many feel inadequate or embarrassed to engage with teachers due to their own lack of educational attainment or unfamiliarity with the system. These examples of an alliance between mothers and teachers suggest how institutional staff can help Latina mothers translate aspects of their motherhood capital into teachers’ terms and receive respect and response.

Blocked Negotiations in Healthcare

In healthcare facilities, these mothers faced an institutional environment with a complex and confusing medical bureaucracy, hierarchical doctor-patient relationships and a dominant perception of Latinos as ignorant clients rather than as partners in their children’s healthcare. This environment exacerbated the lack of cultural capital commonly experienced by most immigrant or low-income clients. This environment also makes it difficult for mothers to effectively use their motherhood capital.

Delfina recalled that, when applying for her daughter’s MediCal, her case workers “speak Spanish, but never calls back…. if you go in personally, you can’t meet with them…” Eventually, Delfina went to the case worker’s office and waited for hours until she came out.

Norma remembered that when her son was in the ICU for a serious brain injury, she noticed an infection and informed the nurses. She was told repeatedly: “Oh, it’s nothing. It’s fine.” Before her son was released from the hospital, she confronted the doctors: “You haven’t noticed, but I have. The stitches here are full of pus.” The healthcare professionals finally took her seriously and found a serious infection.

While half of the mothers shared similar examples of successful if arduous confrontations in healthcare settings, the other half reported that their negotiation efforts were blocked before reaching the desired outcomes. Even when interpreter services were available, these mothers often felt handicapped by these informal barriers.

Empowering All Mothers

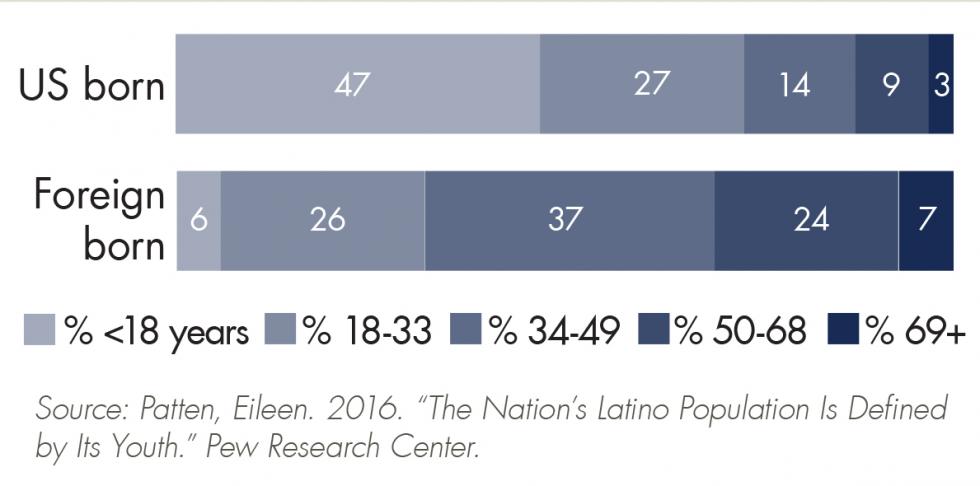

How institutions support Mexican immigrant mothers and families in advocating for their children is important, considering that these children are the future of America. Hispanics are the largest minority group in the U.S. (16% according to the 2010 Census).

Institutional environments matter. This finding should contribute to policy discussions on what defines culturally competent social services. To increase service professionals’ understanding of immigrants’ cultures is important, but policy discussions can benefit from incorporating a stronger focus on reforming institutional features that put immigrants at a disadvantage by amplifying their lack of cultural capital.

Concrete institutional features can help mothers leverage their “motherhood capital,” namely, how deeply they care for and understand their children, to improve their children’s education and healthcare outcomes. These features include a simple and localized bureaucracy and the recognition that immigrants are not only service recipients but also potential partners in their children’s care.

Ming-Cheng Lo is a Professor of Sociology at UC Davis.

[1] See Anspach, Renée R. 1993. Deciding Who Lives: Fateful Choices in The Intensive-Care Nursery. UC Press; Lareau, Annette. 2011. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. UC Press; Shim, Janet K. 2010. “Cultural Health Capital: A Theoretical Approach to Understanding Health Care Interactions and the Dynamics of Unequal Treatment.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior.

[2] Includes publicly funded emergency rooms at hospitals, clinics and hospitals receiving qualifying low-income children.

[3] All names in this brief are pseudonyms.

#povertyresearch