Support from Family Does Not Replace the Social Safety Net

By Ellen Whitehead, Rice University

Discussions of the safety net available to families in poverty overwhelmingly focus on government assistance programs. An additional component of how many families make ends meet is with support from their private networks, especially from parents, grandparents, or extended family. For some, this “private safety net” can support material needs not sufficiently met though earnings and public assistance.[1] However, some individuals may lack connections to family members who can provide such support. Understanding how access to a private safety net varies by group is key to assessing kin support’s role in alleviating material hardship.

Receiving kin support has real implications for material hardship. For example, single mothers who live in multigenerational households have lower odds of poverty.[2] Receiving help with childcare increases employment for many mothers.[3] Among those with sufficient levels of wealth in their extended family, financial gifts or loans can fund education or help make a down payment on a home.

Key Facts

- In addition to the public safety net, support and resources from extended family members are a key way for many individuals to provide for themselves and their children.

- Rates of received kin support are high among relatively disadvantaged populations such as Blacks, Hispanics, and new mothers, but families with high levels of socioeconomic resources have an enhanced ability to offer significant, transformative financial support.

- Because of socioeconomic inequalities between family networks, kin support does not provide for the needs of all individuals, but exploring these transfers can help identify the most vulnerable and isolated populations.

Among families that can make small cash transfers, even $10 or $20 at a time may help with day-to-day needs and emergencies. For all types of support, help from family members provides a resource many otherwise may not have had.

Types and Rates of Kin Support

Important types of material or instrumental support from extended family members include housing, cash in the form of gifts or loans, and childcare. While government programs exist to provide assistance to disadvantaged individuals within each of these three domains, the availability of this assistance is often limited, and many individuals who are eligible are not receiving support.[4]

All three of these forms of kin support enhance an individual’s overall resources. Housing support enables families to pool resources and share expenses. Cash provides a direct, additional source of income. Childcare provided by a family member allows a parent to work, increasing their earnings while also saving money on the high costs associated with daycare or babysitting.

The receipt of kin support often serves as an indicator of socioeconomic vulnerability. Demographically and economically disadvantaged populations, such as Blacks, Hispanics, and single mothers, receive assistance from family members at high rates. However, the type of resources transferred, the value of the support, and expectations of reciprocity all vary depending on the overall socioeconomic status of the family network.

For poorer family networks, mutually sharing resources serves as

a way to cope with poverty. Rates of reciprocity are high within

these families, and extended family members both receive and give

resources. For example, individuals can both receive and give

money to other family members, and they can reside as either a

“guest” or a “host” when sharing housing.[5]

In more advantaged family networks, individuals often

receive help from comparatively better-off relatives. Help often

comes in the form of direct cash transfers.[6] Adults embedded in

relatively better-off family networks have this advantage, and

receive a greater net benefit from the kin support they

receive.

New Mothers and Family Support

Mothers who recently gave birth, a demographic group with high levels of need,[7] show the difference kin support can make. Data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Survey, which includes a high number of unmarried mothers, shows that 57 percent of mothers receive residential, financial, or childcare support from family members during the first year of their child’s life.[8]

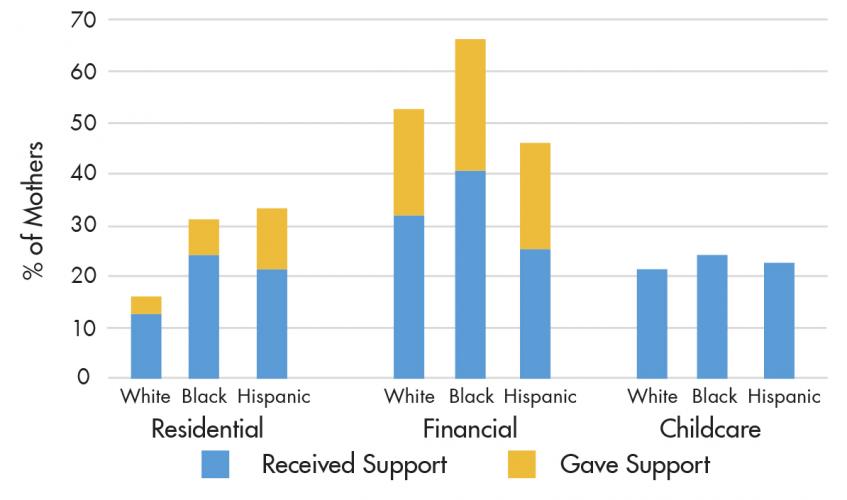

The rates and the characteristics of support vary substantially by race. Both Black and Hispanic new mothers are more likely than White new mothers to live in a relative’s home or to host a family member. Black mothers of newborns more often receive or give more money than White mothers (41% versus 32%). Roughly 24 percent of Black mothers received help with childcare from relatives, a slightly higher rate than White and Hispanic mothers. Hispanic mothers, in contrast, have relatively lower rates of financial transfers with family members.

Disadvantages of Kin Support

Although these informal transfers often help to make ends meet, kin support does have some disadvantages, and does not replace a strong public safety net. For resource-rich families, providing help to a relative may not have negative consequences. For families already struggling, supporting other family members in poverty may restrict their own ability to save and take care of their own future.

Researchers have found that these informal cash transfers play a role in maintaining the racial and socioeconomic inequalities between families. Providing help to family members at high rates prohibits Black families from making wealth-producing investments.[9] Black families are more likely than Whites to be embedded in family networks with higher rates of poverty and to make repeated informal cash transfers to family members.[10] As a result, Black families face a more constrained ability than Whites to accumulate wealth and invest in resources such as homeownership and the establishment of formal financial accounts.[11] The large financial gifts among White families gives them a long-term advantage.[12]

Supporting Vulnerable Families

The need to turn to kin for assistance indicates the difficulties faced by many individuals and families. Considering the role of kin support can enhance our knowledge of the populations most vulnerable to poverty and how public policy can best meet their needs.

The differences in the types of resources transferred, and how these vary by race, demonstrate that many inequalities exist in terms of the extent to which family members are able to prevent or buffer the effects of poverty. Families that are wealthy can make major cash transfers without negatively impacting their own situation. However, families in poverty who provide support can become constrained from accumulating wealth in the long term.

High rates of received support that reduce material hardship indicates that the private safety net helps to meet the needs of many Americans. However, even with family support, those in poverty still may not be able to meet their financial, housing, childcare and other needs.

Ellen Whitehead is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at Rice University. In 2015 she was a Center for Poverty Research Visiting Graduate Scholar.

[1] Kalil, Ariel et al. 2010. “Mothers’ Economic Conditions and Sources of Support in Fragile Families.” Future of Children.

[2] Mutchler, Jan et al. 2009. “The Implications of Grandparent Coresidence for Economic Hardship among Children in Mother-Only Families.” Journal of Family Issues.

[3] Radey, Melissa. 2008. “The Influence of Social Supports on Employment for Hispanic, Black, and White Unmarried Mothers.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues.

[4] Kalil, et al. 2010

[5] Cohen, Philip N., et al. 2002. “In Whose Home? Multigenerational Families in the United States, 1998-2000.” Sociological Perspectives.

[6] Shapiro, Thomas M. 2004. The Hidden Cost of Being African-American: How Wealth Perpetuates Inequality. Oxford.

[7] Nichols, Laura, et al. 2006. “The Economic Resource Receipt of New Mothers.” Journal of Family Issues.

[8] Whitehead, Ellen. 2016. “Residence, Race, and Shared Resources: Does Kin Support Matter for Neighborhood Attainment?” Working Paper.

[9] O’Brien, Rourke L. 2012. “Depleting Capital? Race, Wealth and Informal Financial Assistance.” Social Forces.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Heflin, Colleen M., et al. 2002. “Kin Effects on Black-White Account and Home Ownership.” Sociological Inquiry.

[12] McKernan, Signe-Mary, et al. 2014. “Do Racial Disparities in Private Transfers Help Explain the Racial Wealth Gap? New Evidence from Longitudinal Data.” Demography.

#povertyresearch