Shelter Funding for Homeless Individuals and Families Brings Tradeoffs

By Igor Popov, Stanford University

Each year, over 1.5 million Americans rely on homeless programs for overnight shelter.[2] These programs provide beds and services, and they act as a last resort for many of the most impoverished individuals and families in the U.S. In a new study, I found that a higher level of federal funding successfully shelters those who would otherwise be unsheltered, with little evidence that it increases the total of individuals in the homeless population. However, homeless families move to communities with more generous programs, so non-residents also benefit from local funding. This fact may affect local government incentives to fund programs and services.

Nearly 1.5 million Americans spend the night in a homeless program each year. Despite robust federal funding for homeless assistance, over 200,000 on any given night are without any shelter at all, sleeping in the streets, their cars or other places not meant for human habitation.[3] A wide variety of programs, largely run by non-profits, aim to solve this problem. These programs range from traditional homeless shelters to dedicated, permanent housing accompanied by services.

Key Facts

- A permanent $100,000 annual increase in federal homeless assistance decreases the size of the average community’s unsheltered homeless population by 35 single adults and 11 people in families.[1]

- More generous funding does not draw any new single adults into the local homeless population, but communities with disproportionately generous funding have larger family homeless populations.

- Locally, more funding leads to greater family homelessness because families move to regions with more generous funding. In the presence of such migration, local governments may be incentivized to under-provide homeless services.

Some blame a lack of adequate funding for these programs for the prevalence of unsheltered homelessness in the U.S. These advocates often argue that the best way to combat homelessness is to simply provide entire housing units to those in need at little or no cost. Others argue that the needs of homeless households cannot be met by traditional programs. Skeptical policy makers worry that more generous funding may hinder housing independence for households on the margin of homelessness, without actually addressing the obstacles of those sleeping on the streets.

In new research, I tackled this research question to clarify and quantify the tradeoffs associated with increasing homeless program funding at the community level. In particular, I explored whether increases in federal homeless assistance reach the intended recipients, and whether policy makers should worry that homeless funding draws additional people into the local homeless population.

Measuring Responses to Funding

The vast majority of agencies that provide homeless programs are funded by federal grants administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). These grants are distributed regionally to units called “Continuums of Care” (CoCs). Homeless program providers use these funds to add beds and services for both individual and family programs.

However, an outdated formula sets each CoC’s funding eligibility. As a result, about one in four dollars of funding eligibility is determined by the share of each CoC’s housing stock that was built before 1940. This variable remains in today’s funding eligibility formula for historical and political reasons, and causes similarly needy communities to receive very different funding allocations. I use this variation to quantify the direct effects funding has on homeless populations and the relevant tradeoffs inherent in expanding homeless assistance.

I use homeless population data from two sources. First, all households entering or exiting homeless programs that receive any federal funding anywhere in the United States respond to a standardized survey. Through this process, service providers gather information on demographics, income, government benefit receipt and residence prior to entry. Second, each CoC counts its sheltered and unsheltered homeless populations every other year, administering short surveys to unsheltered homeless people for basic demographics. I construct a dataset using aggregated reports of both types of records, along with federal funding data and a broad set of additional relevant factors.

How the Homeless Respond to Funding

Service providers operate separate programs for single individuals and families, and the analysis shows that homeless individuals and families have quite different characteristics and behavior patterns. Communities that receive more funding have, all else equal, larger homeless populations. However, homeless families—meaning households with children—explain this entire effect.

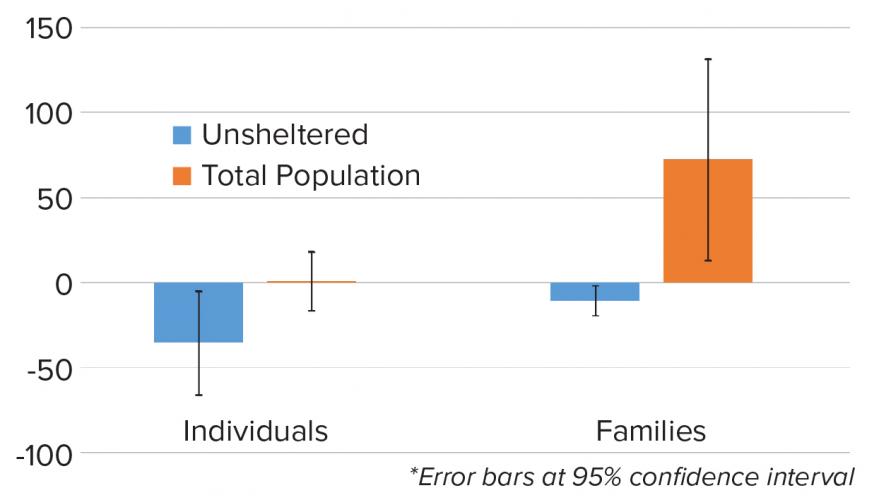

Greater generosity in funding for programs targeting individuals reduces the number of unsheltered homeless without drawing other individuals into the local homeless population. A permanent $100,000 annual increase in homeless assistance decreases the size of the unsheltered individual population by 35, and all of the individuals who utilize the additional beds would otherwise be unsheltered.

The effects of family program expansions are quite different. Families comprise a vulnerable and important subset of the population who utilize homeless programs. The data show that on average they account for nearly 40 percent of the homeless population at a point in time, but also that many families who enter homeless programs have very short homeless spells.

The analysis shows that more generous funding for family programs helps house otherwise unsheltered families but also increases the homeless family population. Every $100,000 increase in annual funding shelters another 11 individuals in families but also adds 73 additional people to a community’s total homeless family population.

Homeless families who move to an area in search of available beds explain at least two-thirds of this increase. Areas with more generous funding serve more families who were previously homeless elsewhere. This means that these households would still be homeless in the absence of the additional funding. I also find evidence that areas with disproportionately greater funding for family programs receive more families who had previously relied on family and friends for shelter and support.

Sheltering Homeless Individuals and Families

As a whole, this research shows that homeless populations do respond to incentives and relocate in search of better services and opportunities. The estimates suggest that very few, if any, individuals who could find shelter by other means choose not to because of more generous supportive housing programs. As a result, the benefits of expanding funding for programs targeting individuals likely outweigh the costs.

The finding that families migrate in response to levels of funding generates two policy implications. First, homeless household migration may reduce local government incentives to provide them homeless services. The prospect of attracting homeless residents from nearby areas occupies many city council meeting discussions on homeless program funding and expansions, though these discussions rarely focus on families.

Second, family migration itself implies that the distribution of federal homeless assistance does not adequately reflect a local community’s level of need. The funding inequities that underlie this study’s analysis also lead to migration costs for families in search of available beds. Moving is likely to be especially costly for children[4] by disrupting their schooling and community environment. If funding tracked area need more closely, many homeless families could avoid these costs.

Igor Popov recently completed his Ph.D. in economics at Stanford University.

[1] In the homeless services center, families are defined as households that include children or a pregnant woman. Individuals are single adults and households without children.

[2] Annual Homeless Assessment Reports to Congress, 2010-2014

[3] Point In Time Count Data, 2011, 2013.

[4] Oishi, Shigehiro et al. 2010. “Residential Mobility, Well-Being, and Mortality.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

#povertyresearch