Charting Students’ Pathways out of Poverty

Education Researcher Studies the Pipeline from Middle School to College and Jobs

By Alex Russell

In the classroom at Kit Carson Middle School in Sacramento, Michal Kurlaender sits at one of four small desks pushed to face each other. The walls are papered in yellow, red and bright blue, and wavy corrugated borders frame a flutter of papers under the banner “AMAZING.”

Kurlaender is interviewing a teacher as part of her evaluation of the school’s teacher development program to improve students’ college readiness skills. The sudden, grating buzz of the class bell startles everyone. Kurlaender smiles. “It’s nicer when it’s the music instead,” she says.

Associate Professor

Michal Kurlaender from the School of Education talks with Oscar

Lozano, 14, about how his poem is developing during an American

history class at Kit Carson Elementary School in Sacramento.

Gregory Urquiaga/UC Davis photo

A middle-school classroom is a familiar place for Kurlaender, an associate professor in the School of Education at UC Davis and a member of the Center for Poverty Research executive committee. She taught middle school before she started toward her doctorate at Harvard University. Her research today on education from K-12 through college could help change the lives of students in poverty nationwide.

Researching Education and Inequality

The program at Kit Carson is supported by a grant from the California Academic Partnership Program of the California State University system to improve expository reading and writing among middle school students. Since Kurlaender started her evaluation of the program, she has expanded her scope to learn about how middle schoolers connect what they do in the classroom to what it takes to go to college.

“I was eager to start thinking about the pipeline to college in a different way,” says Kurlaender. Her most recent work has been on community colleges.

Higher education provides an important pathway out of poverty, she says. This makes Kit Carson an ideal place to learn about what factors might keep students on a track to college. The school serves a high proportion of disadvantaged minority youth from across Sacramento. During the 2013-14 school year, the School Accountability Report Card considered more than 87 percent of its students socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Kurlaender studies transitions students make from middle school to high school, high school to college, and also to jobs. She is trying to understand how policies and programs can make those transitions more or less successful, especially for students who historically have not had an easy path to college, such as students from poor families, students of color, new immigrants and students whose parents didn’t go to college.

Teacher Shawn

D’Alesandro confers with Kurlaender during American history

class. Gregory Urquiaga/UC Davis photo

That these students have a difficult path to college is part of what maintains inequality, she says. Lots of evidence from a variety of research disciplines shows that more schooling, especially a bachelor’s degree, leads to higher-paying jobs. It also leads to better health, greater civic participation and more happiness in life.

To understand how to help disadvantaged students stay on the path to a bachelor’s degree is complicated, says Kurlaender. “Getting kids in the door is only one part of it, but we know less about how to keep them there.”

Community Colleges Make a Difference

Community colleges are one important bridge for many students, says Kurlaender. They offer shorter-term certificates and degrees that students can pursue on a part-time basis. She is working with Center for Poverty Research director Ann Stevens right now to study how these shorter-term programs pay off.

They have found that two-year degrees at California community colleges increase earnings by more than 25 percent. Even shorter-term certificates increase earnings by about 10 percent. Health-related training programs have particularly large returns. This especially benefits women who make up most students in those programs.

“She is one of the most well-rounded researchers I have ever worked with,” says Stevens.

Kurlaender is a quantitative researcher, which means that that she applies statistical methods to large datasets. This is how she can find out how much on average people earn after completing an Associate’s degree or a professional certificate. Stevens says she also spends a lot of time building relationships.

“Because she’s really trying to understand what they do, institutions trust her with access to incredible sources of data for analysis,” says Stevens. “Most researchers don’t do this.”

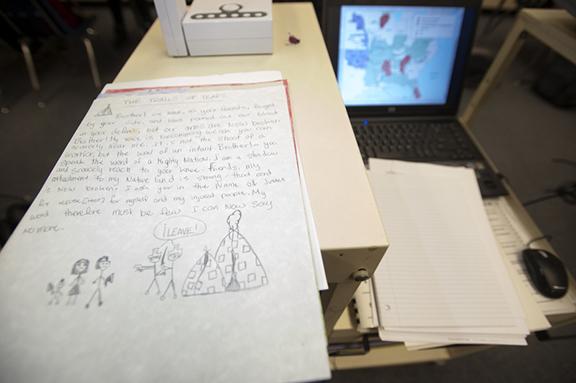

Previous

work gave inspiration to students writing a poem based on the

history of the Trail of Tears in teacher Shawn D’Alesandro’s

class. Gregory Urquiaga/UC Davis photo

Previous

work gave inspiration to students writing a poem based on the

history of the Trail of Tears in teacher Shawn D’Alesandro’s

class. Gregory Urquiaga/UC Davis photo

Learning Research and Policy

For a researcher, says Kurlaender, there is always a personal connection to the work. “There is definitely a personal narrative that led me to think about whether there is an American dream, and how immigrants who come here achieve it.”

An immigrant herself, Kurlaender was particularly focused on whether and how the education system provides opportunities for different types of students. She spent several years working in the classroom teaching middle school social studies, which she continued part-time during much of her graduate studies at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Her graduate work was uniquely multidisciplinary. She trained with statistician John Willett, economist Richard Murnane, and sociologist Christopher Jencks. She also worked on the Harvard Civil Rights Project, a think tank devoted to bridging education, law and policy. At the time, the federal government was reducing its oversight on mandatory school desegregation, school choice was on the rise and districts needed support in building new policies for assigning students to schools.

It was there she fell in love with research. “I realized that for all of these policy questions, I could actually apply data to answer them,” she says. “Once that opened my eyes, I found my home.”

Joining the School of Education

Kurlaender joined the UC Davis School of Education in 2004 as an assistant professor. The school had only recently grown from an academic division at UC Davis. “At that time we had a very limited budget, but had a lot of dreams about what we wanted to be,” says School of Education Dean Harold Levine.

He says since she joined the faculty, Kurlaender has put her time where her values are, which means really dissecting important issues in education and making her work available both to fellow researchers as well as policy makers and others in the field. She also devotes time toward helping build a community of scholars, both inside the School of Education and across campus.

“She brings great visibility to the school’s excellence but she also really takes seriously the idea that we are a community. She hosts events at her home and reaches out to new faculty to make them feel welcome. She is really part of the glue that binds us together.”

In 2013-14 she was named a Chancellor’s Fellow. This past December, she became a co-director of Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE), a policy research center based at Stanford University, USC, and UC Davis.

Mentoring Students

However, she says that the best part of being at a university is the teaching. “My very favorite part of my job is working with graduate students,” she says. “I get to geek out with my white board while we build a research design to better understand a social phenomenon.”

For the past three years, Kelsey Krausen has helped conduct focus groups and interviews at Kit Carson with the principal, teachers and students. She is a Ph.D. candidate at the School of Education. Kurlaender is co-chair of her dissertation committee.

“Working with her has been hugely important to my time at Davis,” says Krausen. “She takes graduate students who are passionate in building their own research and she really guides us through that process.”

Melissa Montes, a UC Davis undergraduate Education major, has worked with Kurlaender at Kit Carson since October. She applied through Aggie Job Link. At first she was entering data in the computer. It wasn’t long until Kurlaender trained her to conduct interviews.

“When I started, I had no research experience,” says Montes. “Now I have the confidence to apply to masters and Ph.D. programs because I feel like I can do it too.”

Educators at the White House

This past fall, Kurlaender was invited with a handful of other researchers to the White House College Opportunity Summit on expanding access to college for low-income and disadvantaged students. The Summit included remarks by President Obama, Vice President Biden and First Lady Michelle Obama about the importance of college and new initiatives underway by the White House, including the College Scorecard.

“She has a knack for understanding what the most important policy questions are,” says Marianne Page, an economist and the center’s deputy director. She is working with Kurlaender and economist Scott Carrell on an evaluation of the Davis School District’s Gifted and Talented Education program.

“She goes from huge, cumbersome quantitative analyses to working one-on-one in schools to gain insights from both perspectives,” says Page.

Students at Kit Carson

The research at Kit Carson is long-term and comprehensive. For their original sample, Kurlaender and her team interviewed 144 7th and 8th graders. This is a very high number of interviews to conduct. “That’s what happens when you have a quantitative researcher doing qualitative research,” says Kurlaender.

This year those students are in 10th and 11th grade and Kurlaender and her team have already talked with 94 of them. She got test scores from the district and collected surveys from students assessing their own academic skills. During interviews she has asked them what they want to be when they grow up and if they have a sense of what it takes to get there.

Camille

Chappell, 14, gets input from Kurlaender about her poem during

American history class. Gregory Urquiaga/UC Davis photo

Camille

Chappell, 14, gets input from Kurlaender about her poem during

American history class. Gregory Urquiaga/UC Davis photo

She also asked how they were doing more broadly and how they seek help when they are struggling. She says she would not have thought to ask these kinds of questions if she had not been speaking with other Center for Poverty Research affiliates like psychologist Ross Thompson, or Leah Hibel, who researches human development.

Kurlaender plans to follow the kids at Kit Carson into either college or the workforce. Knowing what factors make a difference for the paths these students take can help shape policies that improve future students’ chances of lifelong success.

“You could throw your hands up and say that these inequalities are impossible to combat,” says Kurlaender. “We have a great responsibility for children in our society and policies around opportunities for schooling should ensure that the accident of your birth or the circumstances of your childhood do not predetermine your life.”